Home Story The Yosemite of Africa

The Yosemite of Africa

Feature type Story

Read time 13 min read

Published Mar 07, 2021

Author David Pickford

Photographer David Pickford

Story & Photography | David Pickford

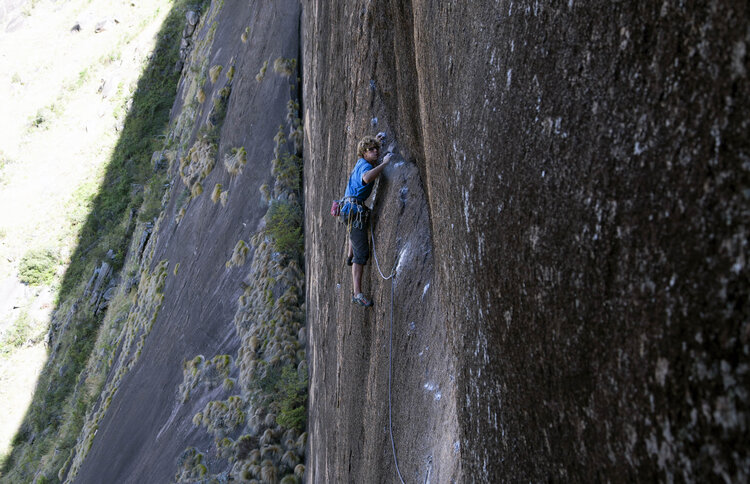

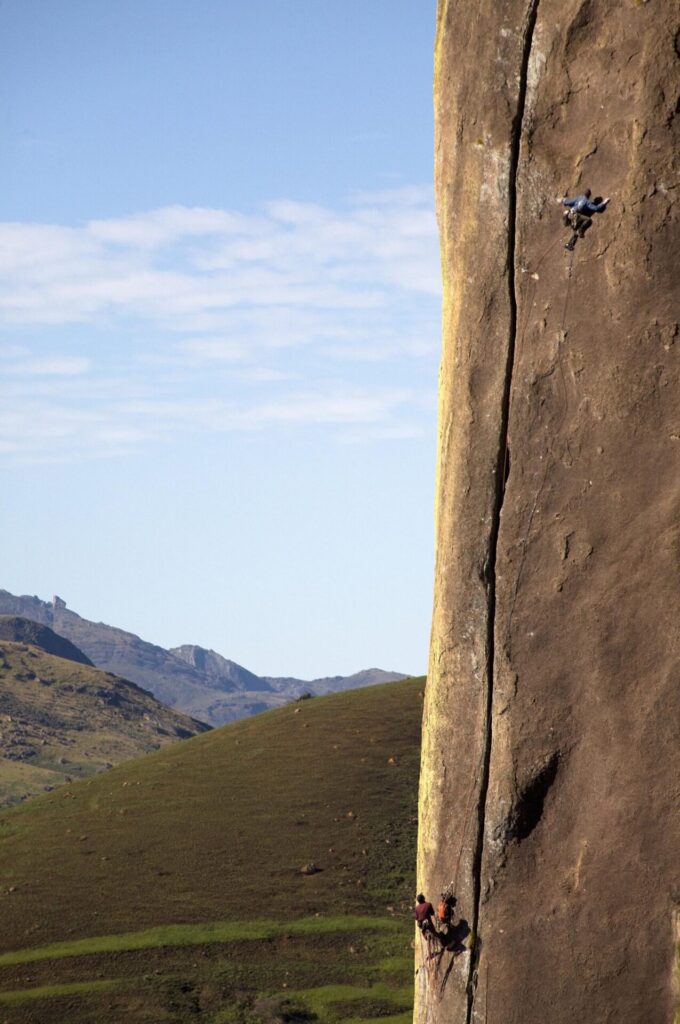

Jack Geldard practices an alternative and very difficult first pitch to Yellow Fever (7c max, 220m) on Lemur Wall – the team ended up abandoning this initial pitch and approaching the line from the right.

We’d been driving for sixteen hours straight when it started to rain. Huge thunderheads were building along the horizon to the east, and the humid night air crackled with electricity. We pulled over to tie tarpaulins down on our luggage strapped to the roof of the jeep.

“Very good idea,” our driver murmured in heavily accented French, and a wry smile spread across his face. “To stop bandits!”

The four of us burst into laughter at the thought of a few tarpaulins fending off raiders, although we were more concerned about our supplies of climbing rope and equipment getting soaked by the storm than the possibility of kidnap. Satisfied with the job, our driver lit another cigarette and started the engine. The rain drummed on the roof of the jeep like a jackhammer. As we rolled off into the night, a ten-second burst of sheet lightning illuminated the wild country to the west, and along the horizon to the south we could see the jagged shadow of a mountain range.

“It’s over there!” Jack pointed into the maelstrom, as the lightning continued to spit fire across the jungle.

“The Tsaranoro massif!”

I couldn’t have expected a more dramatic first sight of the place that has become known to climbers across the world as the Yosemite of Africa.

The stars were so bright it seemed they might burn holes in my mosquito net

Preparations for the expedition had lasted several months, and we arrived in Madagascar at the beginning of April – the end of the rainy season and the beginning of the southern winter – with a month to complete our main objectives. We wanted to establish a completely new big wall free climb, and attempt the uncompleted project route called Tough Enough? which finds a way through the centre of a sheer fifteen-hundred foot monolith called Karimbony. This climb already had an almost mythical status among some of the world’s best rock climbers since the line was first established in 2005. Despite various attempts, it had not yet seen a free ascent.

We arrived at Tsaranoro just before midnight, after a twenty-hour journey south from the capital, Antananarivo. The electric storm that had lit the final part of our journey had passed. I lay in my sleeping bag and looked up at the shadow of the Tsaranoro massif towering thousands of feet above us. The stars were so bright it seemed they might burn holes in my mosquito net. It felt incredible to be here at last, in the heart of one of the most exciting and exotic climbing areas in the world.

After making various ascents of some of the established, classic routes to acclimatise to the subtropical heat, we went in search of an unclimbed cliff where we could create our new route. After a day of trekking around the massif, cutting new trails and scoping the crags with binoculars, we found a perfect, natural climbing line on the righthand extremity of a cliff called Lemur Wall – so named because of the endemic Madagascan primates who populate the jungle at the base, along with many other exotic flora and fauna. The line stretched upwards for around six hundred feet, following a striking yellow streak in the black granite.

A ring-tailed lemur up to mischief; these animals are prolific in the Andringitra National Park.

The hanging vine didn’t snap, much to Jack’s disappointment – climbers have a natural tendency towards schadenfreude in such situations

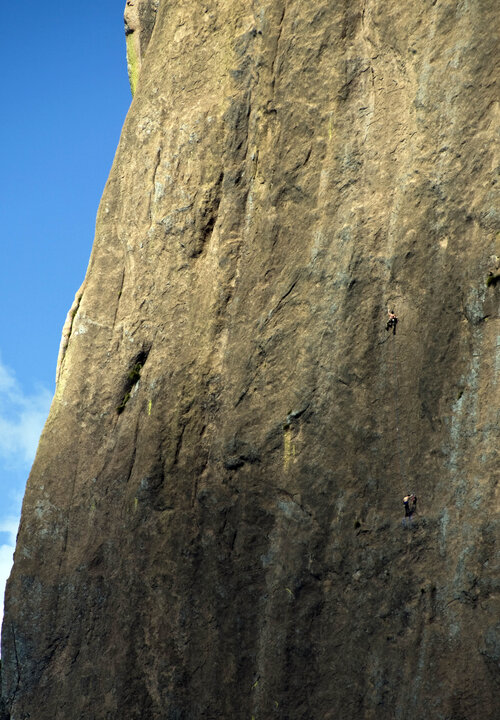

Jack Geldard (leading) and James McHaffie on the Madagascan classic Rain Boto (7b+ max, 350m) on Karimbony.

A ring-tailed lemur up to mischief; these animals are prolific in the Andringitra National Park.

During our first day on the route, Jack and I bolted and established the first pitch ground-up, with a view to free climbing it after we had practised the moves. This initial section of the wall seemed to be the hardest, involving very difficult technical face climbing on microscopic holds. We tried to free climb it the next day, but failed due to the mercilessly rough rock and hot conditions. That night at base camp, I suggested that we needed an alternative approach to the main challenge of the line above.

Back up at our advance base camp under the wall, I studied the rock on either side of the existing first pitch with an open-minded approach. The wall to the left seemed even more blank and impossible than what we’d been trying to climb. Jack and I looked up at it, and defeat seemed to stare back us. But then I had a brainwave.

To the right, a gigantic vine hung down the side of an overhanging gully. If we climbed it, I worked out that we could probably make a traverse out to a point just above the ‘impossible’ lower section of the wall and the top of the first pitch. I made the leap of faith, placed a bolt runner for protection, and grabbed the vine. Swinging out on it and then climbing, Tarzan-style, to a tiny ledge about forty feet up was certainly one of the most unusual experiences of the expedition. Amazingly, it didn’t snap, much to Jack’s disappointment – climbers have a natural tendency towards schadenfreude in such situations.

I soon realised that this lucky ‘tarzan vine’ was our key to free climbing the entire route. We made a belay at the tiny ledge, and I set off on the second pitch: a spectacular traverse that swooped out across the wall to re-gain the yellow streak. It was getting dark by the time we’d completed it, so we abseiled off and returned to base camp.

One of the friendly creatures you might encounter whilst trail-breaking in the Madagascan bush. Fortunately, the colours are just for show; in a parallel of New Zealand, no poisonous animals live on the island of Madagascar.

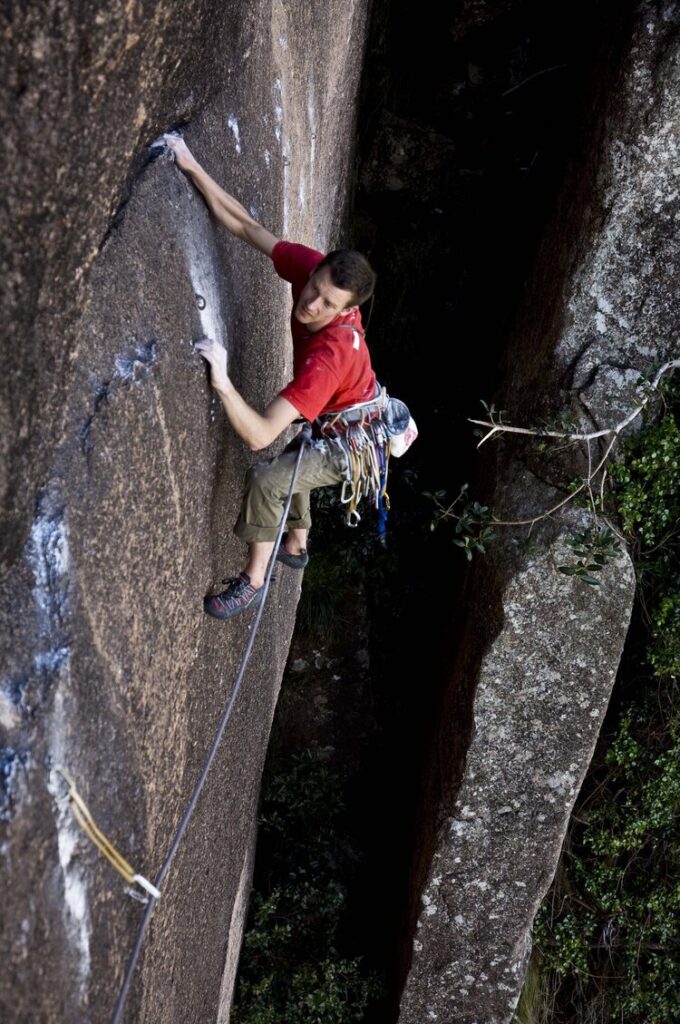

One of the not especially accommodating handholds on pitch 8 of Tough Enough? (8b+ max, 380m) on Karimbony.

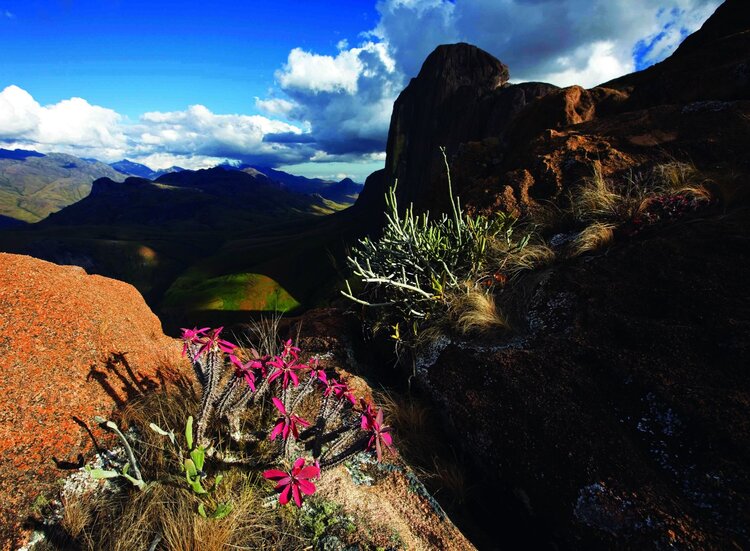

Looking north towards Tsaranoro Be from the summit of Karimbony.

DID YOU KNOW?

-

Madagascar is the world’s fourth-largest island. It contains four percent of the world’s total plant and animal species, of which circa 80% are endemic.

-

The first humans didn’t arrive on Madagascar until circa 500 A.D.

-

The first settlers were not sub-Saharan Africans, but voyagers from Indonesia and the eastern Indian Ocean.

-

Madagascar has its own order of endemic primates, the Lemurs. They are prolific throughout the island; the ring-tailed lemur (lemur catta) thrives in the Tsaranoro region. A lemur the size of a gorilla once existed on Madagascar but was hunted to extinction.

-

In 2009, a bloodless military coup ousted Madagascan President and former yogurt baron Marc Ravalomanana, replacing him with a former DJ, Andry Rajoelina. Such power transitions are not uncommon on the island.

The following day Jack lead off up what would become the hardest section of the whole route, a huge pitch that took the upper part of the yellow streak. Despite the threat of a huge fall from the most difficult section, he locked into ‘the zone’ and free climbed through this crucial impasse. The final pitch was a relative breeze, and we knew the line was ours. Because of the striking coloured streak in the black granite that had originally drawn us to the line, we decided on Yellow Fever as a name for the route (its companion line to the left is called Ebola).

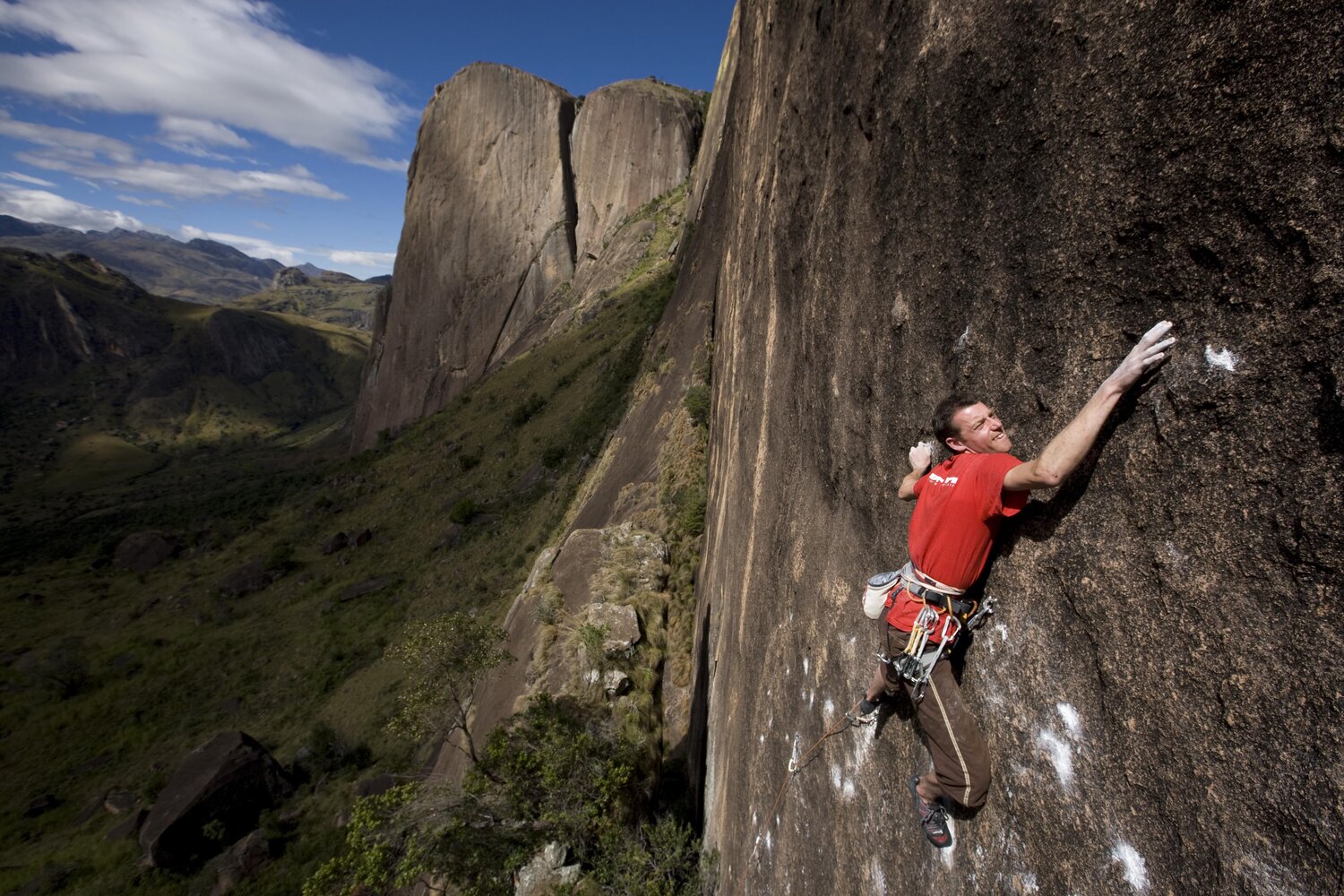

Flushed with success from our new route, James and I turned our attention to the project known as Tough Enough? on the West Face of Karimbony, the awe-inspiring granite monolith that dominates the right hand side of the Tsaranoro Massif. This huge, featureless expanse of golden granite gleams in the morning sun, as if God had taken a cheese slice to a colossal chunk of marzipan.

On first acquaintance, it is hard to imagine how it would be possible to free climb the west face at all. No consistent line leads up it. Spidery flakes and tiny cracks spiral through the bright green lichen, heading nowhere. There is barely a single ledge anywhere on the wall big enough to balance on without a handhold. Many of the holds are just single crystals of granite, sometimes only a few millimetres wide. Tough Enough?, in short, is the definition of modern big wall free climbing.

The climb consists of ten separate pitches, and we began our attempts on the lower four pitches of the wall. I made the first free ascent of the introductory pitch – a sustained and technical 40 metre face climb – on my first attempt. Later that day, James worked on the very difficult third pitch, whilst I practised the similarly tricky second one below it. At nightfall, we abseiled back to the base of the wall, and made the familiar return to base camp through the jungle by headtorch. The following day James and I succeeded in free climbing the two hard pitches we’d rehearsed the previous afternoon. In high spirits, we managed to climb the fourth pitch afterwards, just before it got dark.

James McHaffie practices the crux (eighth) 8b+ pitch of Tough Enough? (8b+ max, 380m) on Karimbony, and one of the world’s greatest big wall free climbs.

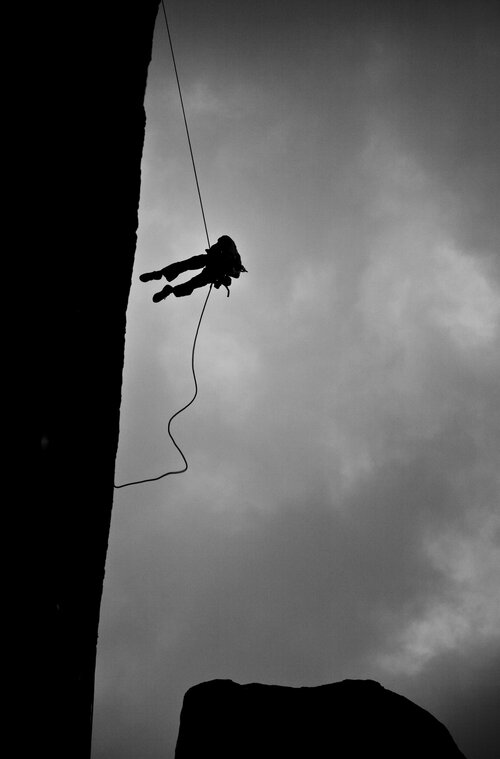

After a rest day, we hiked up to the top of Karimbony to approach the upper pitches from above. Abseiling over the edge of the West Face gives a major overdose of exposure: there was nothing but a thousand feet of sheer, blank granite between us and the ground. James managed to free climb the ninth pitch of Tough Enough? – the most difficult section of the entire route – late that afternoon, after a huge fall ended his first attempt high on the headwall.

We both almost fell asleep with exhaustion on the summit that evening: the physical and psychological strain of Tough Enough? was beginning to take its toll. We stumbled down to the fixed ropes above Lemur Wall in the falling dusk. The solitary lights of base camp began to float up through the darkness. Stopping for a rest on a huge boulder on the way down, we looked back in silence at the shadowy form of Karimbony.

With only a few days left before our expedition drew to a close, and the possibility of free climbing every single pitch of Tough Enough? looking unlikely, we decided to enjoy climbing a few of the other established routes around the massif. On our last night at base camp, I realised I’d been as captivated by the extraordinary landscape and resilient people of the region as much as by the exceptional big wall climbing in the Tsaranoro massif itself; and I had already begun to plan a return to the magic mountains of Madagascar.

Jack Geldard seconding the second pitch of Yellow Fever (7c max, 220m) on Lemur Wall on the first ascent.

Don’t miss a single adventure

Sign up to our free newsletter and get a weekly BASE hit to your inbox

Other posts by this author

Story • David Pickford • Apr 12, 2023

West by Northwest: Lundy Island by Standup Paddleboard

An open-water SUP voyage from the north coast of Devon to the iconic island of Lundy

Story • David Pickford • Jul 24, 2022

Vectors in the Stream

A voyage between islands across some of the world’s strongest offshore tides

Story • David Pickford • Feb 04, 2022

Tidelands

Travels in the unexpected wilderness of the Bristol Channel

You might also like

Photo Essay • BASE editorial team • Mar 18, 2024

Hunting happiness through adventure in Taiwan

BASE teams up with adventurer Sofia Jin to explore the best of Taiwan's underrated adventure scene.

Story • BASE editorial team • Nov 21, 2023

Five Epic UK Climbs You Should Try This Winter

Craving a snowy mountain adventure? Inspired by the Garmin Instinct 2 watch (into which you can directly plan these routes), we've compiled a list of five of the best for winter 2023-24!

Video • BASE editorial team • Jul 04, 2023

Zofia Reych On Bouldering, Life And Neurodivergence

Climbing is a driving force in Zofia's life, but for a long time, it also seemed to be a destructive one