Home Story The Line Between Simplicity and Insanity

The Line Between Simplicity and Insanity

Feature type Story

Read time 10 mins

Published Mar 01, 2022

Author Chris Hunt

Photographer Johny Cook

Rule #1: you cannot cross a tarmac road.

Rule#2: The land you cross must all be open access.

Rule #3: You must follow one continuous, straight line.

Dig deep enough into the fringes and you’ll find an ardent few well-versed in the art of straight-lining; pouring over maps through a very specific lens, planning routes with a stripped-back approach which see purity, simplicity and insanity all jostle for attention in equal measure.

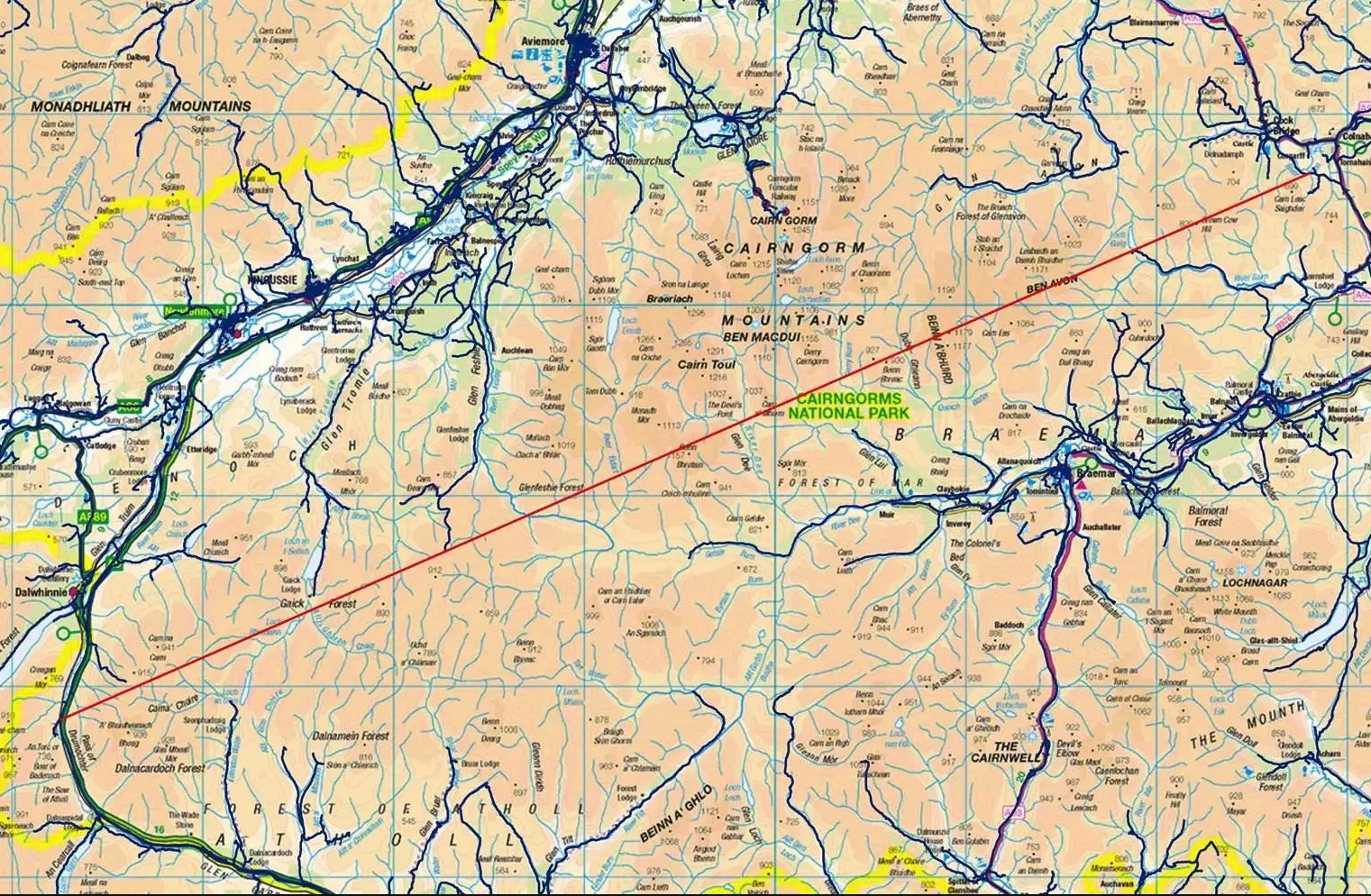

In 2019, filmmakers Matt and Ellie Green from Summit Fever Media stumbled across an Ordnance Survey article citing the king of the UK’s straight lines – a 71.5 kilometre line scored across munro, riverbed, bog and heather spanning the width of the Cairngorms National Park – and set about assembling a stiff-necked team to pursue it.

Now, with the international release of their film The Longest Line, we take a deeper dive into the project and its characters.

Putting It All On the Line

The more niche the project, the harder the sell. With this in mind, Matt and Ellie knew they needed a team willing to be equally enthralled by the concept and its location. First port of call: Scottish adventurer and outdoor swimming enthusiast Calum Maclean.

‘I couldn’t turn down the challenge,’ says Calum. ‘I like ideas, and this idea was beautifully simple. It felt like exploring my backyard, but in a totally new way.’

The idea was too good not to share and he knew just the person who’d match his enthusiasm, commitment and personal connection to these lands: world-record breaking endurance cyclist and fellow Scottish adventurer Jenny Graham.

‘I’d been chatting with Calum about another project and he was like, actually, I’m going to do this thing in the Cairngorms next week, walking in a straight line,’ says Jenny. ‘He hardly gave me any information and I hardly asked. I was just like, alright, seems cool. I basically signed up on the spot, and just went with it.’

With about 20 kilos each of sleeping systems, food, tents and camera equipment strapped to their backs, Matt, Ellie and adventure photographer Johny Cook set out to document Calum and Jenny’s journey.

As soon as we hit the heather, it was like death by a thousand cuts

‘Initially we thought we could just do the whole thing with them. Like, how difficult could it be?’ says Matt. ‘But as soon as we hit the heather, it was like death by a thousand cuts. And there’d be sections of peat hags where even though they were dry, you’d be stepping up and down like a metre or something at a time. Doing that kilometre-after-kilometre started to feel a bit like some weird Cross Fit torture.’

With a renewed appreciation for trail systems everywhere, the film crew went in search of simpler terrain. Faster and a lot less painful, they soon discovered tracks running almost parallel to the line. Now though, with no phone reception or eyes on their subjects, with plenty of terrain between them, they were totally clueless of their proximity to one another.

‘We had it easier in some respects, because we could avoid a lot of the heather-bashing, but we had some panicky moments,’ remembers Matt. ‘We’d reach a point, and be like, have they gone past here? Should we wait? Should we go ahead?’

Exposed for four days in the north of Scotland, with a strike window dictated by existing commitments, one thing is for certain: you’ll want the meteorology gods on your team.

‘We were so lucky, I can’t even explain it,’ says Matt. ‘The river levels were so low. But you could tell by the size of the river beds in the valley that, on a wet week, quite honestly, I don’t think you would be able to get across.’ Still, crags are still crags even under the best weather conditions. ‘Coming past the cliffs at Devil’s Point, you stand there and think, wow, okay, if we were like 150 metres that way or 150 metres the other way we would be in some quite serious climbing territory. It was just slabs and because of the angle, they were wet and greasy so you really wouldn’t want to be there. There were constant challenges but let’s be honest, there’s a reason why there are trails in the places there are, and there’s a reason why you don’t even see animal tracks straight up and down hills and stuff. Because it’s not a sensible, efficient route.’

At One with the Line

Dissecting almost the entire width of Cairngorms National Park, it’s only through sheer luck that the line avoids the most technically demanding features. There’s no denying though that these are Scotland’s wildest landscapes and having barely laced a pair of boots in the past year, Jenny knew that no mile would come easy.

‘I’m a keen hiker and I’m in the Mountain Rescue team, so I knew I had it in me. But on the first day, my ankles hurt so much, I was a bit like, oh, no, what if I’ve bitten off more than I can chew here? They’re going to have to help me limp off the hill. But thankfully, that didn’t happen. Your body soon adapts, doesn’t it. It’s so clever.’

Finding some form of a rhythm in the line, committed Jenny and Calum would do everything in their power to stick to it like glue.

‘Navigationally, it ended up being one of the toughest expeditions I’ve ever done,’ says Jenny. ‘You think you know what a straight line is and then you look ahead, and you have to sort of cut the land up into sections and you end up going in really strange directions because of the camber of the terrain. It sounds strange, but when we were traversing around a gully or a steep hillside, staying exactly on this straight line doesn’t necessarily mean walking in a straight line. But it was our sole focus, our entire purpose for being out there. We both have quite obsessive personalities. The things that we go off and do by ourselves, they mean nothing to anyone else, but we can get completely absorbed by them. Once I set my mind to it, I knew I’d stick to that line and I knew that Calum would too.’

For four days, this arbitrary line across scree and scrub was their entire world. Everything they’d experience before them on this one direct path. But with the novelty of the concept starting to fade, monotony would surely creep in.

‘The highs and lows weren’t extreme enough to counteract one another,’ she says. ‘We were never scaling this huge mountain that we weren’t sure if we would get up and it was never so hard that we felt like we couldn’t physically go on. We both knew that we could do it, we just had to keep going. It was a bit dull in places and we were travelling incredibly slowly – like some days we were averaging one mile an hour. It was laughable.’

Result of fatigue or tedium, soon enough, despite their best efforts, stepping off the line would be inevitable.

‘The one time we went majorly off, it was probably a couple hundred metres. We were on this flat plateau in some of the big mountains. We’d topped out. It was first thing in the morning and it was beautiful. We’d just been chatting and I looked down, like oh, no, we’re totally off the line. We’d just met the film crew and took our eye off the ball for literally like four minutes. And that was it. Way off.’

An integral part of any purist straight-lining mission is of course checking for accuracy. And as is the case in any niche scene worth its salt, the straight line disciples have constructed the tools to ensure precision is held to the highest standards.

‘There’s a website where you can upload your GPX file to check how straight your line is because this is a whole thing. And so Calum uploaded our route but because of that major navigation error on the plateau, we scored zero. But when he took that I and maybe there was like one or two that we just wiggled off slightly, we got we got like 90% or something. So over four days, with this huge line to follow, we were quite chuffed with that.’

We both have quite obsessive personalities. The things that we go off and do by ourselves, they mean nothing to anyone else, but we can get completely absorbed by them

Aside from the fatigue, the grazes and the blisters, having reached the tarmac just south of the hamlet of Corgarff, with the complete 71.5 kms in the legs, what remains?

‘The initial reaction when we finished was like, I never want to see a straight line ever again,’ recalls Matt. ‘I think particularly for Calum and Jenny having gone through that forest at the end — like it’s one thing doing a straight line in open ground, but in a wood… oh my word! But actually since then, I’ve definitely got some other straight lines in mind. And I think, if we weren’t carrying like 20 kilos of food, tents and camera equipment, it would be a lot more fun.’

Shortly after the film was shown at Kendal Mountain Festival, the wave of influence was fast building momentum as people started to replicate the formula to create their own straight-line adventures.

‘A lot of the people who like the film can go out and do this for themselves and that’s really cool to see!’ he continues. ‘We’re not talking about climbing K2 or something, where there’s a lot of things in the way of being able to achieve that. We’re talking about something that, even if you don’t want to do the longest line across the Cairngorms, you can introduce the principle to where you enjoy hanging out.’

For our protagonists, these mountains have been both playground and mentor and in clocking the countless hours exploring its peaks and valleys over decades, it’s a place they hold close to their hearts.

‘I can look around the Cairngorms and picture all the different adventures I’ve had here, solo or out with friends and different trips, ski-touring, biking, hiking, camping and they’re very, very dear to me,’ explains Jenny. ‘It’s a place that I love to be and where I really feel like I cut my teeth in learning all the skills I needed to go off into bigger mountain ranges and do bigger things. I thought I knew them inside out. Well, I know them even better now, for sure.’

‘This journey summed up the last couple of years for me perfectly. Here’s an area that Calum and I have both explored and explored, explored and almost feel like we’ve rinsed all the good stuff. And this just turned all that on its head. I didn’t know anything about straight-lining as a concept, until this and then I find out there’s a whole community of people that are mad for it. And that’s so cool. When you see something like this happening, it broadens your horizons, seeing that there’s other people doing really silly things. I love that.’

Walk Your Own Line

For Calum, living relatively close-by, the journey is one he’s reminded of regularly.

‘It always makes me smile when I drive past the start point now,’ he says. ‘It’s a fairly plain, boring bit, right on the A9 but it now means something to me. I always think, wow, we actually went and did that! Not because it’s a hugely impressive feat but because of the madness of it!’

So now, having experienced the madness first-hand, is this format one that will continue to shape his own adventures?

‘I’m not a complete straight-line convert but I’ll definitely do a shorter version. I’d consider one using a compass and travelling on a bearing, without the instant feedback from the GPS. I’d still track it and check my route after to see how I did, but the enjoyment of the journey is more important to me than just staying on an imaginary line. I think it’d have to include something more than just walking next time too – maybe I’d combine it with a swim.’

Original takes on adventure can feel rare within a tight community focussed on the same small handful of locations. Every now and then though, a project like this comes along, leaving behind it a door just slightly ajar – enough perhaps to unleash a refreshed perspective on the land around you.

‘If you get an inkling of an idea, take it on,’ says Calum. ‘It could be fun, or hard, or great – the mystery of not knowing exactly what’s to come and how you’ll get on is exciting. Take something you know well and simplify it down to the most basic element or style you can. Placing restrictions and parameters will force you to be creative. I’m a big fan of the motto coined by my friend Stuart Macleod: just dae stuff!’

Don’t miss a single adventure

Sign up to our free newsletter and get a weekly BASE hit to your inbox

Other posts by this author

Story • Chris Hunt • Jul 04, 2023

Evolution of Flow: E-mountain Biking in the Swiss Alps

Exploring Crans Montana and the Tièche valley on two wheels

Story • Chris Hunt • May 05, 2023

Life-affirming discoveries near Bolivia’s Death Road

Sami Sauri explores the winding gravel tracks of the Yungas surrounding La Paz, Bolivia

Story • Chris Hunt • Feb 09, 2023

Throat of The Dog: Bikepacking the Zillertal Alps

A 175km traverse of the mountainous spine between Italy and Austria

You might also like

Story • Kieran Creevy • Jun 16, 2023

Scrambling Before Scran on Scotland’s Misty Isle

Sun-drenched ridge lines with expedition chef Kieran Creevy on the Isle of Skye

Video • BASE editorial team • Jun 02, 2023

How To Clean And Care For Hiking Boots

Our top five tips to give your hiking boots a 'glow up'

Video • BASE editorial team • Mar 30, 2023

How To Break In Leather Walking Boots

5 fast hacks for breaking in your boots, beating the blisters and reducing the ankle rub