Having made it through the tide race on the approach to their objective, the team reach the shallow waters surrounding the Eddystone Reef.

‘About here, she thought, dabbling her fingers in the water, a ship had sunk’

― Virginia Woolf, To The Lighthouse

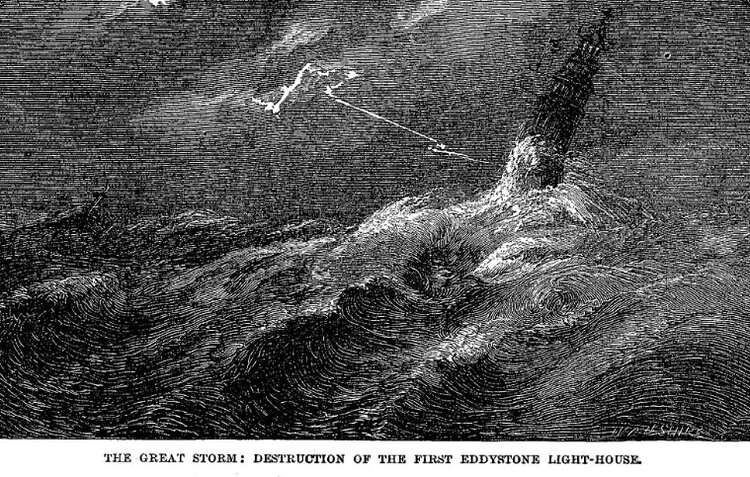

Robert Chambers’ depiction of the destruction of Winstanley’s original lighthouse in the Great Storm of 1703. (Robert Chambers / public)

The English Channel glimmers silver and gold in the early morning sun. The faintest breath of a northeast wind ruffles the water. Nothing but the ghost of a long-lost Atlantic groundswell swirls around the stratified rocks of Polhawn Cove. These are ideal conditions for what we have in mind.

Ten miles out, a solitary column of concrete stands tall in the heart of the sea, commanding the scene off Plymouth Sound like a fossilised version of the Saturn V launch vehicle. It’s an object as incongruous as it is weirdly compelling. Rising from a submerged reef of Precambrian gneiss hundreds of millions of years old, it stands resilient against the sea and the weather that perpetually works against it, warning ships of the danger that lies beneath.

But it has not always been this way. The Eddystone Reef is a major hazard to shipping in the English Channel, and countless ships have gone down on these dangerous rocks. Christoper Jones, the captain of the Mayflower that took the Pilgrims to North America, remarked in 1620 of the ‘twenty-three rust-ragged stones around which the sea constantly eddies. If any vessel makes too far to the south, she will be caught in the prevailing strong current and swept to her doom on these evil rocks’. Considering Jones’s warning, and the growing importance of shipping in seventeenth century England, it’s perhaps not surprising that the Eddystone Reef was the site of the world’s first ever open-ocean lighthouse, which was completed in 1698 under the direction of the maverick inventor, engineer, and merchant Henry Winstanley. A definitive man of the early Enlightenment, prior to the construction of the first Eddystone Lighthouse, Winstanley had designed a mathematical water theatre called ‘Winstanley’s Waterworks’ in Piccadilly. This remarkable contraption combined fireworks, fountains, and automated mechanisms of all kinds, including a rotating barrel serving hot and cold drinks.

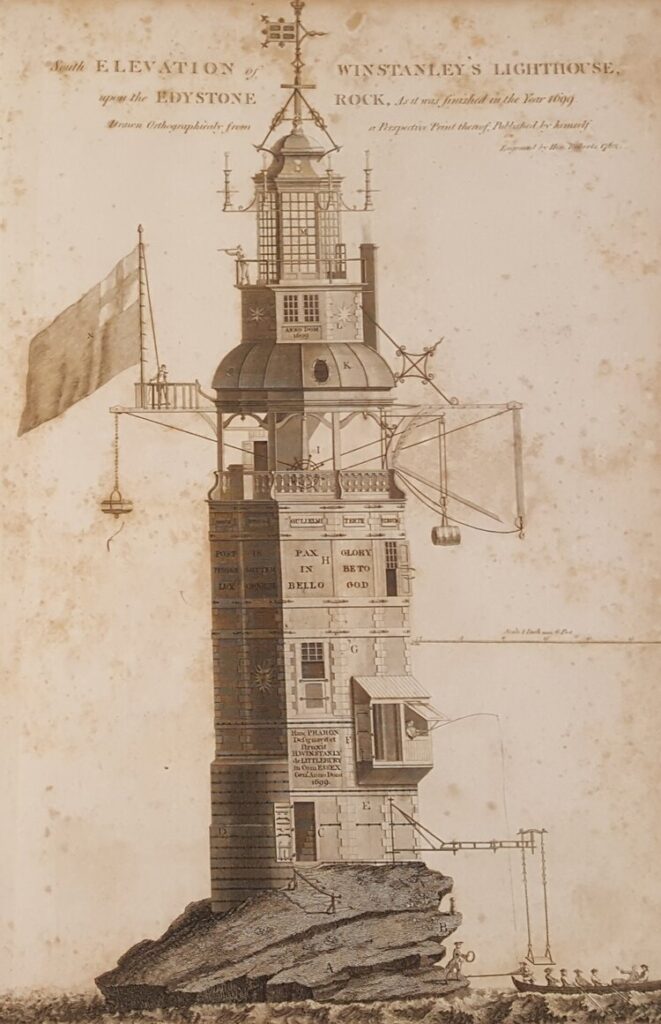

Drawing of Henry Winstanley’s original lighthouse on the Eddystone Reef by Jaaziell Johnston and John Smeaton, 1813. (State Library of New South Wales / public)

After losing two of his own ships to the Eddystone Reef, and having been told by the Admiralty that the rocks were ‘too treacherous to mark’ Winstanley was determined to do something about it and began building a lighthouse on it himself. Construction began in 1696, and two years later an extraordinary octagonal wooden pagoda stood on the Eddystone. Its upper chamber enacted the purpose for which it was built, and was lit by 60 candles at a time supplemented by a huge hanging lamp. The lighthouse was damaged by storms in the first winter of its existence, then rebuilt in 1699 as a dodecagonal structure with a timber frame and stone-clad exterior. It survived for another four years, during which time no ships were wrecked on the Eddystone Reef.

Winstanley was working on the lighthouse himself when the extratropical cyclone known as The Great Storm of 1703 hit on November 27th. By the morning of November 28th, 1703, no trace of either Henry Winstanley or his lighthouse remained on the Eddystone Reef. In a strange twist of fate, Winstanley actually got to experience his own cherished ambition. He reportedly had tremendous faith in the lighthouse, and allegedly suggested he ‘wished to be inside it during the greatest storm there ever was.’

Modern meteorological analysis of the records of the Great Storm of 1703 have suggested it was likely to have been a Category 2 hurricane, meaning wind speeds of 96 – 110 mph. What wildness Winstanley must have experienced that November night on the Eddystone as he confronted the demise of his beloved lighthouse – and of himself.

After researching the history of the Eddystone Reef prior to our voyage out, the extraordinary character of Henry Winstanley began to loom large. I felt a little like Martin Sheen’s Captain Willard in Apocalypse Now as he unfolds the classified file on Colonel Walter E. Kurtz: ‘the more I found out about this man, the more I wanted to confront him’. Since Winstanley died over three centuries ago, I wouldn’t be able to confront him physically. But I could at least encounter the site of his final creation in the most direct possible way – from the surface of the sea itself.

It was this desire, combined with a window of perfect conditions, that led a team of five of us to head directly out to sea on a ten degree bearing SSW from Rame Head, with the Eddystone’s modern Douglass Lighthouse just a needle on the horizon. There are not many better places to be than a mile off the British coast on a deep blue midsummer morning. Spirits in our group were high as a light tailwind sped us along, ruffling the surface of the sea from time to time.

A light container vessel with a black and red hull steaming south behind us crackled up on the radio; ‘Falmouth Coastguard. Number one, number one, over’. Was the captain talking of his ship, or of himself? Who knows. But for our team, there was now only one objective: that slowly-growing concrete pillar at 12 o’clock, a lone sighting-line between the wine-dark sea and the sky.

Ten miles out, a solitary column of concrete stands tall in the heart of the sea, commanding the scene off Plymouth Sound like a fossilised version of the Saturn V launch vehicle

A depiction of the wider destruction of the Great Storm of 1703 in the English Channel. At least 1500 sailors were lost on the Goodwin Sands (shown in the painting) including Rear Admiral Beaumont, and historians estimate 8000- 15000 people were killed in the storm in total. (Unknown author / public)

For our team, there was now only one objective: that slowly-growing concrete pillar at 12 o’clock, a lone sighting-line between the wine-dark sea and the sky

A few hundred metres to starboard, a gannet was diving for fish. An area on the surface just ahead darkened with microscopic bubbles as a shoal of mackerel passed. The bounty of the sea was all around as the land behind blurred into a mirage.

After three hours, the needle on the horizon had begun to resemble an actual lighthouse. As we approached, tell-tale eddies formed around us, a sure sign that the tide was running through shallower water. A kilometre before the reef itself, we hit an area of overfalls. The strange sensation of being in a tide race ten miles offshore wasn’t lost on any of us. It was around high water when we reached the lighthouse, and the reef was entirely covered. The water under us was aquamarine in places as the sun refracted off areas of quartz and patches of sand in the gneiss bedrock. At one point, I caught the silver flash of a bass or grey mullet under the board. The Eddystone Reef is an unexpected, magical marine environment to find this far offshore in a temperate ocean.

The lighthouse itself, of course, dominates the scene. Fifty metres of concrete rising from the waves, impervious to its hostile surroundings and utterly resilient to anything the Atlantic might throw at it: a masterpiece of modern civil engineering. I gazed up at it as we enjoyed a well-earned lunch break drifting on the myriad tidal eddies around the reef, and couldn’t help but feel even more admiration for Henry Winstanley and his outlandish wooden pagoda. Today, in near-perfect conditions, it was hard enough just to imagine it standing here on the reef, a great creaking tower with its grand octagonal prism adorned with candles surrounding the giant central lantern. Conjuring up what it must have been like at the moment it was consumed by the sea that November night in 1703 required an even bolder leap of the imagination. The occasional percussive tap of an impact driver echoed from high up in the tower; even on a Saturday, maintenance workers were here, engaged in the constant task of shoring up the structure. Building and maintaining a lighthouse in a place like this is challenging enough in the twenty-first century, let alone over three hundred years ago.

Reaching the Eddystone Reef, 18 kilometres after leaving the Cornish coast.

In mountaineering, when you reach the summit you’re only halfway there; exactly the same could be said of paddling trips to open-ocean lighthouses. A light south-westerly had been forecast for the afternoon, which would have been a perfectly-angled tailwind to speed us back to England. As is often the case in high pressure weather systems, the wind forecast was unreliable: a Force 3 south-easterly picked up not long after we’d left the Eddystone, causing a bit of troublesome side chop. We still managed a few short downwind runs before zig-zagging back into line with the tidal vector we were taking to return to Rame Head.

All too soon, the south Cornish coast resolved into view; the land had shifted from mirage back to earth and stone. The small chapel atop Rame Head defined our destination-marker as we cleared the headland and entered the sheltered water of Polhawn Cove, receiving some puzzled glances from a few anchored yachts as we came in; clearly their owners didn’t expect a flotilla of loaded SUPs complete with radios and offshore safety equipment arriving here from far out at sea.

In mountaineering, when you reach the summit you’re only halfway there; exactly the same could be said of paddling trips to offshore lighthouses

As the greatest wilderness environment on Earth, the sea is to be treated with the utmost respect. A long offshore trip such as this should only be attempted with the necessary skills, fitness, equipment, and during a spell of settled weather and minimal swell. Every adventurer must factor the unknown into their planning, though. As such, I think there’s something in the remarkable story of Henry Winstanley and his original lighthouse on the Eddystone Reef that all mariners – indeed all explorers – can learn from.

In his noble attempts to protect ships from harm, Winstanley created something never seen before in human history – a large and complex structure on an open-ocean reef. Yet he also fell under the fatal spell of his own invention; he could not distinguish its potential shortcomings from the brilliance and ingenuity of the overall concept. With hindsight and an understanding of modern stress engineering, it was inevitable that a lighthouse made largely of wood would not survive very long on a reef in the English Channel. We know that now, but Winstanley didn’t. And in this sense, like all true explorers, he was right out there at the edge of knowledge. The story of Henry Winstanley’s lighthouse, then, is not just the tale of the rise and fall of a wooden tower on a rock in the middle of the sea, but a story of the expeditionary imagination itself.

Don’t miss a single adventure

Sign up to our free newsletter and get a weekly BASE hit to your inbox

Other posts by this author

Story • David Pickford • Apr 12, 2023

West by Northwest: Lundy Island by Standup Paddleboard

An open-water SUP voyage from the north coast of Devon to the iconic island of Lundy

Story • David Pickford • Jul 24, 2022

Vectors in the Stream

A voyage between islands across some of the world’s strongest offshore tides

Story • David Pickford • Feb 04, 2022

Tidelands

Travels in the unexpected wilderness of the Bristol Channel