Home Interview The BASE Interview #02: Hazel Findlay

The BASE Interview #02: Hazel Findlay

Feature type Interview

Read time 12 min read

Published Mar 04, 2020

Author David Pickford

Photographer David Pickford

Interview & Photography | David Pickford

Hazel Findlay has pushed British rock climbing to new levels in the last decade she’s spent at the top of the game. Today, she’s one of Britain’s leading adventure climbers, with a host of groundbreaking ascents to her credit that, together, form one of the more formidable CVs of any contemporary British climber. In 2012, she became the first British woman to climb a traditionally protected route rated E9 on the British grading scale – a major breakthrough for trad climbing in the UK. Two years later, she became the first British woman to climb an 8c graded sport route – another major leap forward. Shortly afterwards, she became the first British woman to make a free ascent of El Capitan in Yosemite, California – the world’s most famous big wall and the centrepiece of rock climbing in North America.

Alongside her personal climbing, Hazel has developed a specialised mental training programme for climbers wishing to improve, which draws on her reading of philosophy, sports science and flow theory. I caught up with her earlier this year to discuss her life in the vertical, what adventure means to her, and to find out more about her personal philosophy of risk.

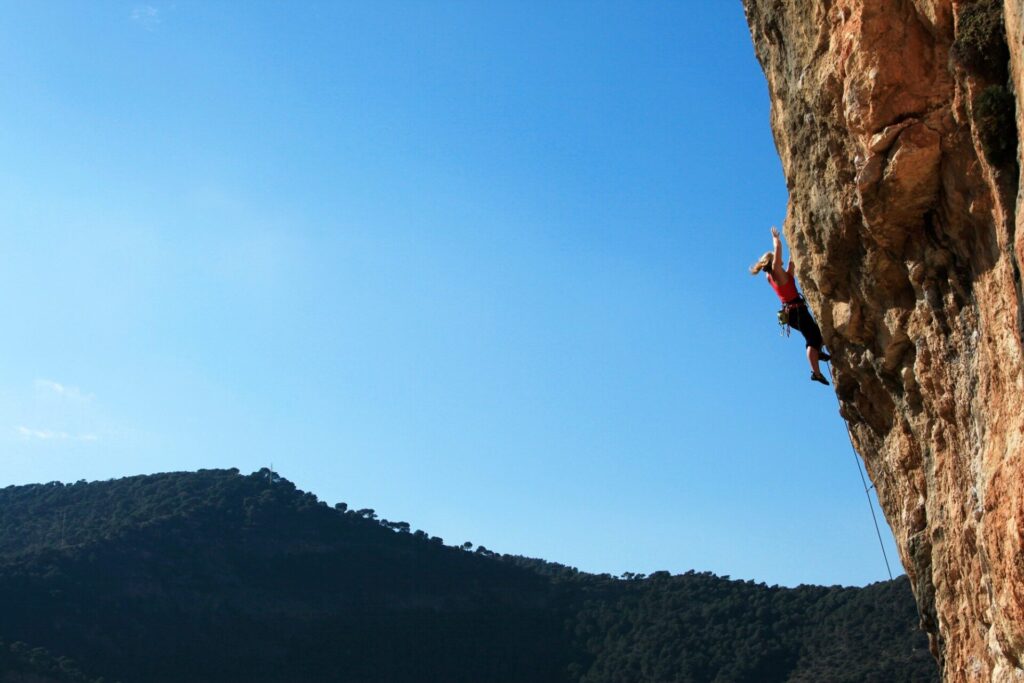

Hazel makes a quick ascent of the hard Italian testpiece The Doors (E8 / 8a trad) at Cadarese in northern Italy in 2012.

As a professional climber, the sport has a key role in your life. Do you see climbing primarily as a sport or more as an adventure?

I guess I see it as an adventurous sport. I’ve always had a hard time considering myself an ‘athlete’ because when I think of athletes, I think of tennis players with training regimes and coaches and tournaments, and that’s not what most of my climbing life has looked like. To me climbing is more than a sport; yet it sounds clichéd to say it’s ‘a way of life’. And it’s more than that too, it’s sort of like a testing ground for me, it’s the place I go to test myself.

This sounds a bit like the Samurai concept of Bushido, the code of honour associated with martial arts mastery that the Samurai warriors were bound to follow.

I think there is a link here. Obviously I’m not an expert in martial arts, but all the mindset stuff I teach in my mental training is about trying to attain what’s often called a ‘mastery mindset’. And through that process of mastering a discipline like climbing, what you learn permeates your whole person and you gain skills that apply to the rest of your life.

Your climbing career has been based around the adventurous side of the sport as opposed to the performance oriented element or competition arena. Was this a conscious choice or a natural process?

I have always just followed what inspired me, and that was adventurous climbing in interesting places. The professional climbing came later when brands decided that they wanted to support what I was doing.

For you personally, how critical is an element of adventure for the climbing experience to have value?

I like climbing for different reasons. I like adventurous climbing but I also just like climbing for the movement and for the pleasure of trying hard and accessing flow. Adventurous climbing puts you outside of your comfort zone which is great, and this is the space where you learn, but you can’t always be in that space. I love hard sport climbing which isn’t very adventurous, but it still has value for other reasons.

What are the key ingredients for adventure, in your view?

There must be unknowns; if you can control everything then it’s not an adventure. Equally you have to be able to leave your comfort zone, which means it’s going to feel uncomfortable at times. This means that you may not be having fun the whole time, but it doesn’t mean that the experience is not valuable. Real adventures are always challenging, which means that you usually always learn something on a good adventure. When you have a true adventure, you instantly know you’re never going to forget it.

When you have a true adventure, you instantly know you’re never going to forget it

Following this logic – the concept the Romantic poet Keats called negative capability – and the necessity of dealing with uncertainty as central to adventure, do you think some people are better suited psychologically to adventure sports than others?

I think the skill of dealing with the unknown can be a trained skill rather than an innate quality. In reality, though, I think the way you’ve been brought up often determines it. If you’ve been protected from challenge and uncertainty as a child and as a young person, then it becomes much more of a struggle, and it’ll just be harder. If you start from a position where you simply can’t deal with uncertainty, then uncertainty becomes a reality, you’re going to have a hard time.

You were the first British woman to free climb El Capitan in Yosemite; the first British woman to climb a trad route rated E9 [one of the highest grade on the rating scale for traditional climbs]; and also the first British woman to climb an 8c rated sport route. All these were major achievements. What do you feel were the biggest milestones in your climbing career personally?

I think all the routes you mentioned were big milestones. It was my dream to free climb El Cap, ever since I saw the videos of Lynn Hill in the valley. It really tested everything I had to climb Golden Gate. The E9 was maybe less of a true test, because the climbing really suited me, but from a career perspective it was really important for me. Climbing 8c was important because it helped me believe that I really was an athlete as well as an ‘adventure climber’.

What’s your view of how first female ascents should be reported in the climbing media and the media at large?

Actually, I think that there is some utility in the first female ascent. As much as people like to say otherwise, there are big differences between men and women. The sport is not a level playing field. The average height of a man is 5.10, I am 5.2. All the routes are graded for the 5.10 man, and it’s useful for me to know when a woman has done a route because chances are she is more similar to me physically. I also think that the first female ascent gives media outlets a bigger excuse to talk about women in climbing, which I think is really important. That said, I don’t think women should chase first female ascents or that we should celebrate every first female ascent.

Does the current media environment make it easier or harder to be a professional female adventure athlete?

Some aspects make it harder and some make it easier. Brands and climbers want to see more female climbers in a sport which is still male-dominated, so in that sense brands are on the lookout for strong female adventure athletes. However female athletes are still sexualised in the industry more than men. So there are more pressures for women to look a certain way. I also wonder whether there is gender pay gap in the industry? We don’t really have data on that.

If there is a gender pay gap in the adventure industry, could it be because some women ambassadors are contracted by brands as ‘athlete models’ rather than contracted as athletes?

The whole subject is largely conjecture, really. Unfortunately sexuality as a commodity is more valuable to a woman than to a man, so it’s more important for a woman to be attractive as an athlete. But I don’t know how this effects the pay gap. It may be contributing to a process where a female athlete’s activities are not taken as seriously as they might otherwise be. Unfortunately it’s hard to talk about this issues honestly as the subject is pretty radioactive.

Climbing has taken you to some really interesting places like Sudan, Mongolia, and Newfoundland. How important is adventurous travel within the context of climbing?

I love to travel and see new places. For me seeing the world is important to understanding it, and the people living in it.

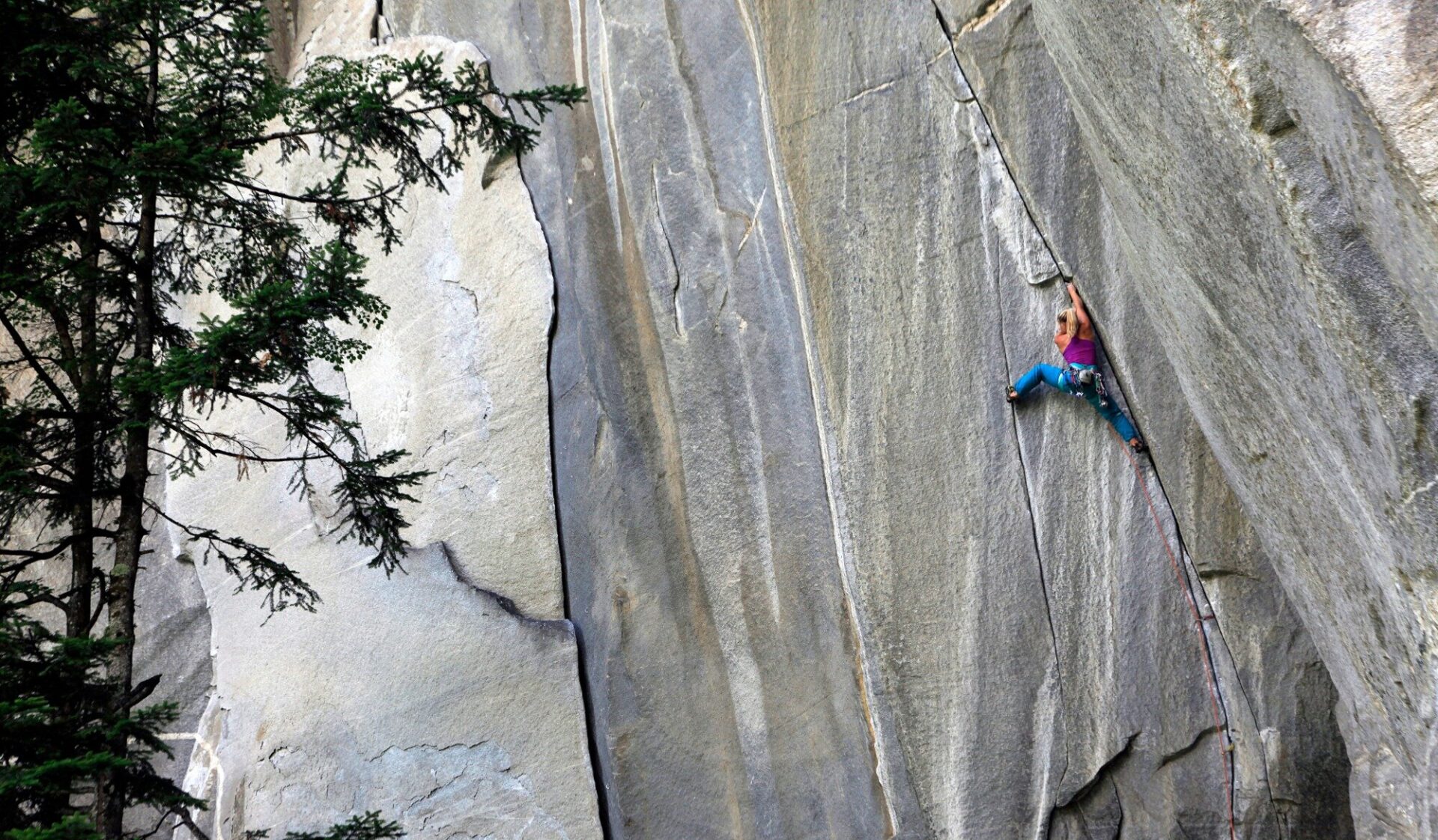

Hazel in her element at Pavey Ark, one of the great trad crags of Langdale, Cumbria.

What’s the most interesting place climbing has taken you?

I recently went to Mongolia which was pretty interesting. It’s hard to believe that there are still people who live nomadically, with no fixed abode. Mongolia is so sparsely populated with very little infrastructure; going there is like stepping back in time.

Is climbing as a vehicle for adventurous travel important?

I wouldn’t have gone to Mongolia just for the climbing. Travel is a really important component for me. I don’t just go to the best climbing places, I go to places that are culturally different, and where you can learn something you might not learn anywhere else.

What are the results of the rise of indoor climbing as a popular fitness activity for many people in the wider context of climbing?

One way of seeing it is as what used to be one sport is splitting into two very different activities. There’s a lot of people now who start climbing with no intention of going outside. Some climbers speak of it as a problem, and I’m not sure that’s quite right. A real problem would occur if too many people started climbing outdoors, because of the environmental impact that would have. Some popular crags are already getting seriously crowded. Will we see crags with ticketing systems in the future? At the moment, you don’t need a permit or ticket to climb outdoors, and that’s part of the joy of it.

You’ve done a lot of research in the field of mental training for climbing, much of which carries over to other adventure sports too. What have been the main results of this work?

The mind is what dictates all the decisions we make, so it’s really important! As an athlete, the mind is the thing that gets you to follow the training program, it gets you to the climbing wall, it keeps you focused. So mindset is everything. People think it’s fixed but it isn’t – you can shift your mindset and make something that you used to see as a waste of time as something valuable. Then there’s the discomfort perspective too; climbing is an uncomfortable sport, and as humans we’re programmed to find heights and falling through the air scary and uncomfortable. But we can re-wire our minds to be OK with that discomfort. Training your mind to be comfortable in uncomfortable situations is crucial in adventure sports like climbing. It’s also useful for other things in life, too.

Isn’t this idea that every reality is a reality of the mind an existential notion?

In some ways it is more of a Buddhist idea, as Buddhism recognises that suffering is an internal experience, just an artefact of our conscious experience. A Buddhist might say that suffering is caused by the habits of the mind, not by the externals. So if you can train your mind not to react in that way, then you don’t suffer. In climbing, in some ways the fear response is rational, as you could be in real danger. But your choice about your reaction is internal, as you can chose how to respond in the most useful way for you to maintain your performance and/or safety.

So we encounter this emotional feedback and therefore feel fear or pain?

Yes, and the observational mind takes time and patience to practise. The cool thing you learn from climbing is learning to respond rather than just react, so you don’t get that tunnel vision. People who are good at this in an adventure context rarely apply it to the rest of their lives though. I find it hard to control my responses in the rest of my life. But you can realise that with the right approach you can apply these processes to the whole of your life.

What are the key psychological barriers for most people in climbing?

Falling is the key one really. I’d say 80% of people have some fear of falling. That’s not to say that people don’t have other limitations, like fear of failure. But they’re less likely to seek coaching for this as it’s harder to diagnose. It takes a lot of patience and persistence to correct it. You can apply the same loading idea to mental training as to physical training. If you take a massive fall and really scare yourself, it could be the same as injuring yourself physically through overtraining. And it will take time to come back from that. There’s still not a proper culture of fall practise, and this is one reason injuries happen.

Do you feel that most people can improve their performance in adventure sports through mental training?

I think everyone can.

Discomfort and struggle is important. We should gravitate towards challenge instead of away from it, and try to gain a positive conception of failure

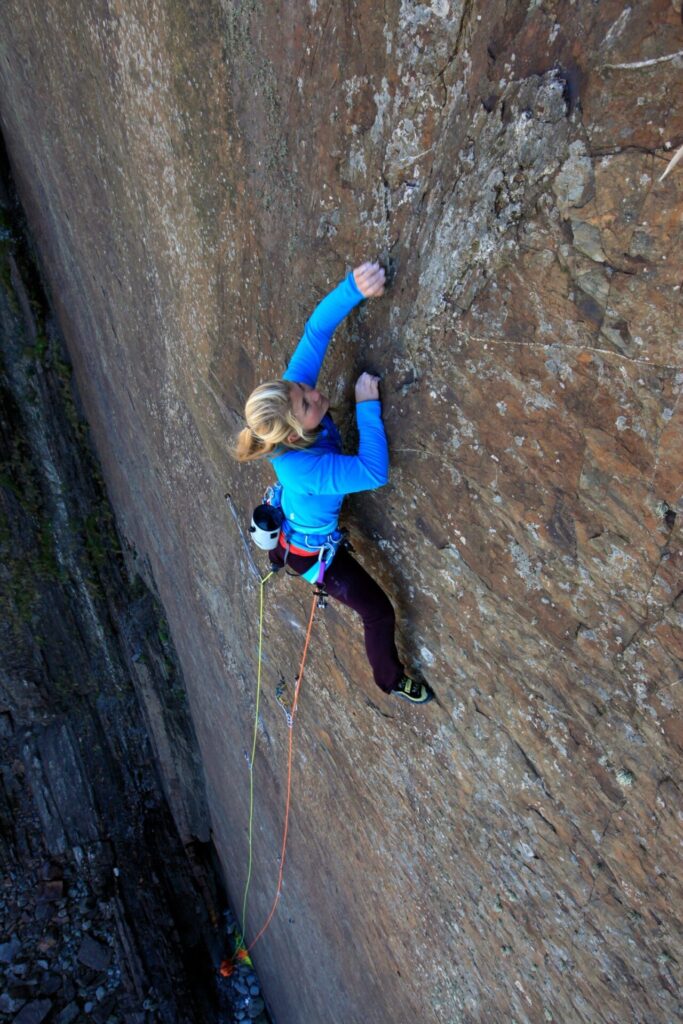

Hazel making the first female ascent of the coveted trad testpiece Air Sweden (5.13c) at Indian Creek, Utah (USA) in 2010.

Training your mind to be comfortable in uncomfortable situations is crucial in all adventure sports

What’s your own approach to risk?

The main thing with risk is you need to be sure that you’re interested in it from an experiential perspective not just an achievement perspective. If you focus on the achievement then you’re just doing it for your ego. I get a bit of a bad taste in my mouth about some of the stuff that goes on in mountaineering for this reason. Some of it seems to be so much about ego, which strikes me as the wrong reason to go into the mountains. Showing some humility out there is crucial.

For some people, interacting with danger is a fundamentally alien and uncomfortable. Do some people have innately capacity for dealing with real risk in a wild environment than others?

We just don’t know enough about the science of nature vs nurture from a personality perspective,. But it’s better for us to think that whatever we’ve got now, we can improve upon what we have, rather than being fixed. Even Alex Honnold talks about how hew trained his mind by soloing progressively harder things. So even the best free soloist ever has still had to put the training in!

What’s the biggest challenge you’ve faced in your climbing career?

Probably my shoulder injury. It was a 7 year long injury and I had 3 years of not being able to push myself, and a whole year out of climbing completely. It taught me about this idea that your suffering is your reaction to the world, I had to learn that I didn’t need external things like climbing to be happy.

How do you separate justifiable and unjustifiable risk?

I think it’s a deeply personal thing. Our relationship with death is really unhealthy, I don’t want to say to someone they shouldn’t do this or that. It’s more a question of thinking about what we should admire. My level of justifiable risk is really low. If I think I might die on a climb I just wouldn’t do it, I don’t need that sort of a challenge. Some risk is okay, but I can learn a lot from low level risk. Some young men feel they can only learn anything from hard alpinism, then they fall in love for the first time and it all changes, when they realise you can learn from many other things in life.

What things learnt through climbing and adventure can benefit ordinary life?

I think a sense of the value of discomfort and struggle is important. And also that we should gravitate towards challenge instead of away from it. Also, prioritising learning rather than ego wins. And gaining a positive conception of failure, and of seeing the process of not succeeding as progression rather than failure.

How do you see your career as a professional climber evolving in future?

This summer I did my first corporate coaching course, teaching the principles I’ve learnt through my climbing coaching in professional situations, so people can get more out of their work on a personal level. That’s what I’m really interested in doing, but I want to explore other avenues with the coaching. I’m 30 now and I do want to focus on my own climbing too. Perhaps I don’t want to be a professional climber for my whole life, particularly if I have a family.

What advice would you give to ambitious young climbers or adventurers?

It’s good to try to learn to do things for the right reasons. Use adventure as a tool for learning, rather than a route to ego gains.

What luxury would you take to a desert island?

I wouldn’t take anything, to get the full castaway experience!

This interview first appeared in BASE issue #2. You can read the full issue here. To keep up with the latest from BASE be sure to subscribe and get every issue delivered directly to your inbox.

Don’t miss a single adventure

Sign up to our free newsletter and get a weekly BASE hit to your inbox

Other posts by this author

Story • David Pickford • Apr 12, 2023

West by Northwest: Lundy Island by Standup Paddleboard

An open-water SUP voyage from the north coast of Devon to the iconic island of Lundy

Story • David Pickford • Jul 24, 2022

Vectors in the Stream

A voyage between islands across some of the world’s strongest offshore tides

Story • David Pickford • Feb 04, 2022

Tidelands

Travels in the unexpected wilderness of the Bristol Channel

You might also like

Photo Essay • BASE editorial team • Mar 18, 2024

Hunting happiness through adventure in Taiwan

BASE teams up with adventurer Sofia Jin to explore the best of Taiwan's underrated adventure scene.

Story • BASE editorial team • Nov 21, 2023

Five Epic UK Climbs You Should Try This Winter

Craving a snowy mountain adventure? Inspired by the Garmin Instinct 2 watch (into which you can directly plan these routes), we've compiled a list of five of the best for winter 2023-24!

Video • BASE editorial team • Jul 04, 2023

Zofia Reych On Bouldering, Life And Neurodivergence

Climbing is a driving force in Zofia's life, but for a long time, it also seemed to be a destructive one