Story & Photography | Sam Hill

Sam is an International Mountain Leader based in Switzerland and the UK, you can find him @hill_adventures

What is it about mountaineering that no matter how many failures you’ve had in the past, you always roll into the next adventure with a totally misguided sense of optimism? It’s childish really, but as the wheels of the plane touched down in Agadir, I couldn’t have felt more positive about what lay ahead.

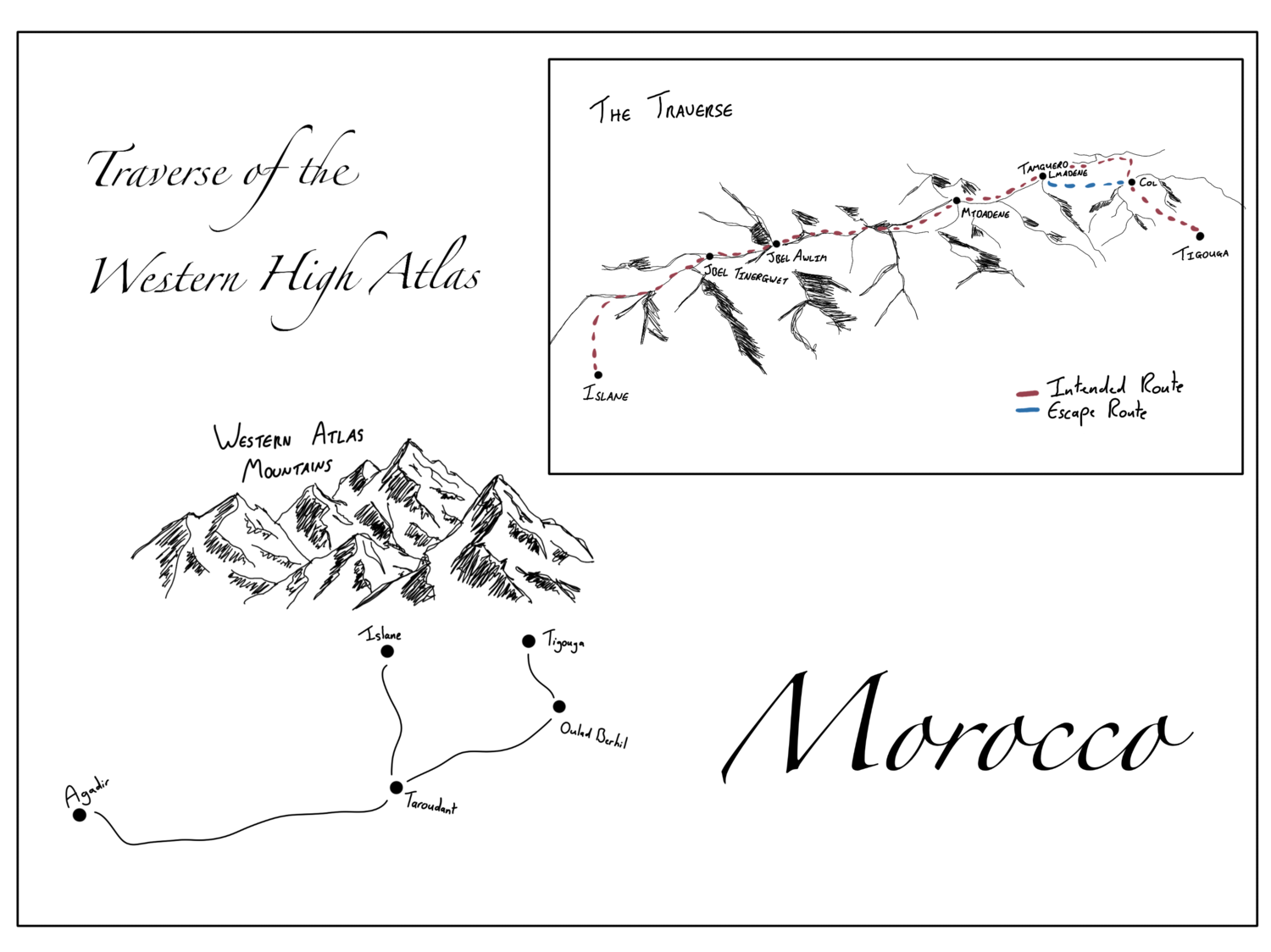

My partner, Fran and I had been planning this foray into the Western High Atlas Mountains of Morocco for a little while. For us, it was a small piece in a much larger picture. We had a more ambitious project planned in Nepal the following October and we needed a chance to test out kit, food and how many arguments we would have when all of our socks had frozen solid. After digging about in guidebooks and online I found a great looking link-up of mountains making up the giant ridgeline of the Western Atlas Mountains. From everything I had read, this was an area that, unlike the Toubkal range, very few people visited – especially in winter. It looked remote, achievable, and really beautiful. Information on the route was limited, but I managed to make contact with George Cave from 67 Hour Adventures, who had completed a winter traverse in 2014 and was really forthcoming with information. He even sent through some of the old Soviet maps they had used to help them in their traverse.

Oh great, we’re either going to get beheaded or die some kind of gruesome mountain induced death

We had decided to stage our trip into the mountains from the old town of Taroudant. It was an easy taxi ride from the airport to the ancient walled city, often referred to as ‘The Grandmother of Marrakesh’. This place doesn’t see a huge amount of tourist traffic and feels like a truly authentic Moroccan experience. On any expedition, I love that first day you spend wandering around a new place trying to find everything that you need. Taking in the smells and sights, getting lost and feeling excited about what lies ahead.

We managed to squeeze enough food and kit into our 35 litre bags to last six days. After stuffing a final chocolate bar into the very last bit of available space in my rucksack, it was time to head to the mountains.

The plan was to get driven to the mountain town of Tigouga, and from there head into the hills to make our way, following the prominent spine of the mountain range, to another remote mountain town called Islane. From there we would hitch a ride back to Taroudant for celebratory tagine and mint tea. I have always found it pretty easy to get around in Morocco, but it does require a bit of research. There is a great network of what they call ‘Grand Taxi’: 6 seater vehicles which drive people between logical transport hubs. The idea is that in most villages there are taxi ranks where you can find a car that is heading where you need to go, and once the taxi is full it will leave. As long as you have some time to spare, it is a really cost-effective way of getting around. The key is to just wander around the taxi rank shouting where you want to go and you will eventually get ushered towards a taxi that is heading your way.

As we rolled away from Taroudant the real adventure had begun. We were turfed out of the taxi in the small town of Oulan Berhil, a roadside settlement made up of a hotchpotch of market stalls and half-built houses. From here we were promised that it would be easy to get a ride to our start point of Tigouga but after a few broken conversations in French and English, we soon established that not many people drove the 2 hours up into the mountains. There was generally a school run on the local bus for the children of the village at 7am and 2pm, but it was 9am and we wanted to get going. So as is often the case in Morocco as soon as you make it clear that you are willing to pay well above the odds, the ball gets rolling. Phone calls are made and someone’s uncle or their wife’s sister’s friend, and eventually, someone make their way out of the woodwork.

In our case, it was a young guy with a beat-up, although delightfully decorated, old Mercedes van. The Arabic music was blaring and we were off on the bumpy, dusty roads into the mountains.

After about two hours of bone-shaking, we arrived in the sprawling mountain town of Tigouga. It was a lot bigger than I had imagined, and the farming settlements were spread out all over the hillside. We jumped out of our ride and were met by a small group of locals. Impatient and gagging to get walking I said hello, but tried my best not get sucked into anything I didn’t need to. I shouldered my bag and stared intently at the map. But it was clear that these men wanted to talk, and were concerned by our presence. We were told that one man, in particular, was the village elder, and he wanted our details. It was explained to us that these mountains were very dangerous and that we definitely shouldn’t camp up there. I did my best to explain that we knew what we were doing and eventually, it was agreed that they would let us go if we gave them our passport details and phone numbers. When I asked one of the men why they wanted these details he simply stuck out his tongue and ran a finger slowly across his neck. Oh great, we are either going to get beheaded or die some kind of gruesome mountain induced death.

If we left this summit and started further along the ridge we were committed, there was nowhere to bug out for another four days at least

With that slightly unsettling interaction dealt with, we made our way through the village and up towards a col that we could see high up in the distance. It was a few hours walk up to the col which would take us onto the high plateau where we would spend the night before getting onto the ridge proper the following day. The night before we left there had been a huge storm, and down in Taroudant the streets had flooded and the rain poured for most of the night. I knew the rain would be falling as snow higher up and in the morning, the host of the guesthouse we were staying in said that it had been years since he had been able to see snow on the mountains all the way from down here. This could throw a spanner in the works.

With the fresh snow on the ground, progress was slow. Any trails that existed were covered over and as soon as we were higher and out of the village, we started sinking up to our knees with every step. We knew that all we had to do was to get over the col, it was a short first day, so we put our heads down and slogged our way upwards. Eventually, after a few episodes of disappearing up to my waist in snowdrifts, the col was there, and as we came over the brow of the hill it hit. Some of the strongest wind I have ever felt. It floored us, forcing sharp icy snow crystals under our sunglasses and partially blinding us. We crawled into the shelter of some boulders and regrouped. We had to get over this col, we couldn’t give up this early, but it was like nothing either of us had ever felt in the mountains. After a few deep breaths, we crawled out from behind our shelter. Fran tucked in close behind me and we pushed ourselves against the brutal buffeting barrage of abuse. As we crawled lower the wind eased, giving us time to scan the map and the landscape around us for some shelter in which to hunker down for the night. We spotted the old ruin of a Shepard’s hut about 2km away and waded through the soft snow in hope of some respite from the elements.

The ruined building would do for the night, and we quickly dug out a spot for our tent. We were going fairly lightweight and the kit we were carrying was sufficient, but in these conditions, wouldn’t guarantee comfort. So we settled in for a long cold night. Regardless of the effort, it had taken to get there, we were in a beautiful place, it felt remote and adventurous, just what we had been looking for. Tomorrow, the forecast was brighter and the climbing would begin.

We awoke to stillness the following morning. I unzipped the tent and we were surrounded by blue skies and the promise of warming sun rays creeping over the snow towards our tent. We were definitely in need of some defrosting! Our boots and socks were soaking from the previous day and everything had frozen solid overnight. After wolfing down some breakfast, frozen feet were forced into even more frozen boots, our rucksacks we stuffed and we set out to get onto the start of the ridge.

Conditions were not perfect. If there had been no storm we would have simply been walking over rock and scrubland, but as it was we were once again post-holing, snow up to our knees, and with every metre gained things were starting to get more tiresome. It will be ok once we are on the ridge, I kept thinking to myself, but after three hours of slogging, things were just as bad. The ridge was made up of blocky boulders, which in better conditions you could scamper across or around easily, but the loose sugary snow meant that every step was uncertain. Would the snow hold, or would my leg disappear into a rocky crevasse? I realigned my expectations. Perhaps higher up it would be be better, the wind would have blasted the loose snow away, and the hot sun would help the snow consolidate ready for the following day. After six hours of trudging, we reached the first major summit on the ridge and our route stretched out before us. In some ways, it looked like a grander version of the Skye Cullin, ridge after ridge, summit after summit, disappearing into the distance. It dawned on us that we had some decisions to make and some questions to answer?

How far do we need to get before we can find a good place to camp?

Does the scrambling get any more technical?

Are we really equipped for the conditions?

If we left this summit and started further along the ridge we were committed, there was nowhere to bug out for another four days at least. Feeling totally wasted, I called it.

“I know we have only just started Fran, but this is going to be miserable. We don’t have enough warm kit, the snow is horrendous and it’s too committing.”

Fran didn’t take too much convincing. We looked at the map, found a safe way off the ridge and headed back down to the plateau.

I always feel deflated making a decision like this, everyone does, but I’ve had to make a lot of them over the years and I’m pretty tuned into my instincts. I know when I should push and when I shouldn’t. So as we trudged down the steep scree slope my mind instantly put this failure behind me and my mind drifted into thoughts of how to turn this trip into a success. Maybe we should head south into the Anti-Atlas…it’s warmer there, I thought.

We didn’t have enough daylight to make it back over the col and down to Tigouga, so we dug out another tent spot and settled in for another frigid night. Failure is always made easier by a long cold sleepless few hours in a tent.

After a morning’s walk back to Tigouga, a six day mission across a remote high ridge had morphed into three days of floundering around in crappy snow, battling winds and getting frustrated. This is what going into the mountains is all about and as painful as it is, you can guarantee that when I am next on a plane, heading into a new set of mountains, I will have that feeling of optimism that I always do, and one thing is for sure, I can’t wait to get back to the Western High Atlas at some point.

Don’t miss a single adventure

Sign up to our free newsletter and get a weekly BASE hit to your inbox

You might also like

Story • BASE editorial team • Nov 21, 2023

Five Epic UK Climbs You Should Try This Winter

Craving a snowy mountain adventure? Inspired by the Garmin Instinct 2 watch (into which you can directly plan these routes), we've compiled a list of five of the best for winter 2023-24!

Video • BASE editorial team • Jul 21, 2023

Merging Two Lives: The Personal Journey of Hamish Frost

The challenges and triumphs of embracing sexuality in the outdoors

Interview • Hannah Mitchell • Jun 13, 2023

Chasing The 14: The Kristin Harila Interview

In conversation with record-breaking Norwegian mountaineer and Osprey ambassador, Kristin Harila