‘No longer can we assume the earth’s resources are limitless; that there are ranges of unclimbed peaks extending endlessly beyond the horizon. Mountains are finite, and despite their massive appearance, they are fragile.’

—Tom Frost and Yvon Chouinard, from the 1972 Chouinard Equipment catalogue

Emma climbing The Big Bang (9a) at Lower Pen Trywn, becoming the first British woman to climb the grade. © Marc Langley

Clean Climbing – then and now

Half a century ago, founder of Chouinard Equipment and latterly Patagonia, Yvon Chouinard, wrote a manifesto of sorts in an equipment catalogue. It was a call to arms, advocating for a new kind of climbing and a renewed respect for the rock, as participation in climbing surged in the late 1960s and into the early 70s.

In that manifesto, Chouinard and fellow climbers Tom Frost and Doug Robinson, implored others to reconsider their ethics, to exercise restraint, and to alter their behaviours in order to protect fragile rock faces for future generations and for the good of the environment. The use of steel pitons, which had been for many years the accepted method of ascending big-wall climbs, was strongly discouraged. Chouinard, Frost and Robinson proposed that climbers might adopt new and less damaging means of ascending, including the use of removable gear such as chocks and hexes. They argued that good style mattered more than reaching the top, and that strength, skill, judgement and a leave no trace ethic were far more admirable than simply sending.

In the years since that first manifesto, climbing has become bigger than Chouinard could ever have imagined, and no longer solely the reserve of the car-dwelling Camp 4 dirtbags. Climbers these days continue to push the limits both indoors on the competition circuit, and outdoors on real rock – Emma Twyford is no stranger to either.

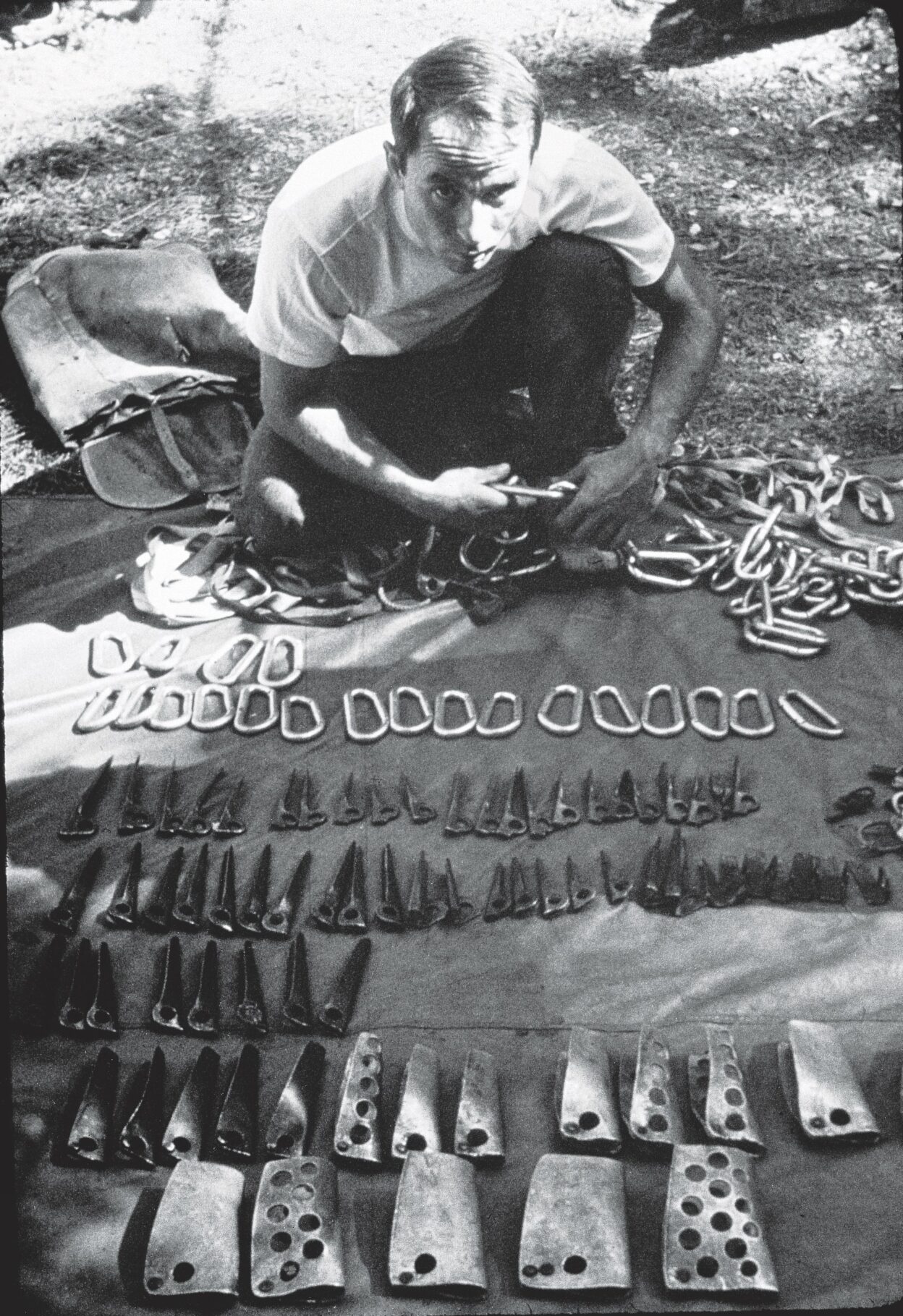

Chouinard with a selection of equipment for sale in Yosemite in the 1960s. © Tom Frost/Patagonia

Introduced to trad climbing by her dad at age seven, you could say that Emma was raised on the rock. A Lake District native now based in North Wales, over the course of her climbing career, she aced the competition circuit to become British bouldering champion and represented Team GB before fully returning to outdoor climbing in her mid-twenties. Emma has ticked a number of prodigious grades in trad, sport and bouldering and in 2019 turned her hand to alpine climbing, making the first British ascent of Camilotto Pelissier in the Dolomites.

Grades and epic ascents aside, Emma is also an experienced professional route setter, passionate environmental advocate and ambassador for both Patagonia and Protect Our Winters. I chatted to Emma about Chouinard’s Clean Climbing ethics, how they apply in modern times, and how the outdoor community as a whole can be better stewards for the environment and for one another.

Emma on the aptly named ‘Vile Crack’ pitch of Longhope Direct (E10 6c), Hoy. © Marc Langley

A lot has changed since Chouinard first coined the term. So, what does Clean Climbing mean in a modern-day context, and in relation to your own climbing?

It’s kind of a funny one, because fundamentally Clean Climbing would be just going climbing without any kit whatsoever and leaving no trace. It would mean everyone soloing, but the reality is that it’s not really ever going to happen. I don’t solo, it’s not a form of climbing that I would do because the consequences for me are too high.

So I guess Clean Climbing to me is trying to climb in the purest form as possible. The ideal would be to place your gear, have the person who’s following you take it out, and leave nothing behind. The reality of that is you’ll probably get chalk everywhere on the rock, and sometimes there is a piece of gear that gets stuck, and you just can’t get out no matter how hard you try – you end up having an epic trying to get it out.

At the end of the day, it is quite a selfish pursuit, so I think it’s just down to respecting the rock and its surroundings. Don’t leave litter, don’t impact on any wildlife or go cutting down trees. Try and brush off any chalk marks that you do leave, brush as you go and try to just always be respectful of the environment and the fact that it isn’t only ours and we weren’t there first.

Like if there are bird restrictions on a crag, they’re there for a reason. There’s plenty of other rock around to climb on, and you’ve got to respect those restrictions and wait for that piece of rock to be available once the birds have flown away. I think it’s just being as respectful as we can be, even if we’re not perfect. And, having that kind of affinity with the environment.

At the end of the day, it is quite a selfish pursuit, so I think it’s just down to respecting the rock and its surroundings

© John Bunney

The accessibility and relatively safe nature of the indoor environment means that many people will begin their climbing careers at the wall, transitioning to outdoor climbing once they have a basic skillset. So, can the outdoor ethics of Clean Climbing be taught at the wall?

Predominantly, people start climbing indoors now, that’s where a lot of people learn. Climbing walls and instructors can offer a safe way into climbing outside and there are definitely fundamental things you can learn indoors, like tying in and how to belay safely. Then you get into kit, and indoors often a lot of that is provided, so it’s about making sure you have the right kit, the right guidebooks, that you have the right route planned – all those sorts of common sense things, and then you can take that with you to the outdoors.

Transitioning into the outdoors presents a myriad of new challenges too; rules to abide by, ethics to respect, and a whole new code of conduct. Where does Clean Climbing fit into that transition and how do we instil those ethics into people who are moving into the outdoors?

Guides and instructors can offer a safe way into climbing outside. I guess a lot of the education side boils down to each governing body within the country. So the BMC in England is educating people from indoors to the outdoors. For example, just as Covid was slowing down, there were a lot more people going outside for the first time because walls were still closed and that was anything you could do. And the BMC made a lot of videos about crag etiquette and safety, and different things like using the RAD app.

And what sort of role can we as a community play in helping to teach people who are perhaps new to climbing how to be more conscientious and adopt a Clean Climbing mentality?

As much as anything, if you see someone doing something not quite right, rather than be like, oh they’re an idiot, go over and explain to them. If you see someone who’s doing something dangerous, try to politely point out to them that it’s dangerous and why, and offer an actual explanation so that people can learn.

A lot of people are very quick to just take to the internet too. Rather than offering constructive advice at the time, they just wait til they get home and moan on UKC!

Absolutely! People are very quick to criticise other’s behaviour on social media, but it isn’t necessarily a productive way to combat it. Can social media be a positive tool for encouraging a Clean Climbing mentality too?

I think you’ve got a lot of professional climbers on social media these days who will call out bad behaviour or etiquette, like when they first arrive at a boulder if it’s tick marked or caked in chalk a lot of them will then put it on social media and say look, this isn’t acceptable. It’s just going about it the right way.

Social media has its pros and its cons. It’s definitely one advantage that people can put things on their stories or feeds that encourage other climbers to just give a little back. Like if you’re at the crag and there’s some rubbish, even if it isn’t yours – take it away. The more people that do bring it up, the more it’s seen, hopefully, the more people are aware of it.

You grew up in the lakes and now you’re based in North Wales. In both of those places, you must be noticing that they’re becoming a lot busier, and that there’s a lot more people wanting to get outside, not only for climbing. It’s a really positive thing for people’s mental and physical health, but there’s also quite an obvious impact on the wild spaces within those areas. How do you think we can balance those two things?

I think because of Covid, a lot more people started to get outside to maybe go for walks or just to go to a scenic spot or to go wild swimming, and sadly things get left behind. Again, the BMC do a lot of work in organising clean-ups nationally, you have the Hills2Oceans campaign and within that you get people who love the outdoors going and doing litter picks, but really the education needs to be there in the first place to advise people of what is and isn’t ok.

I think a lot of it comes down to each local council to lessen the impact of those increased numbers of visitors. For example there is a little Park and Ride system here for the Llanberis Pass – better public transport to these places lessens the impact of vehicles on the areas. Maybe there’s some some sort of role to be made, to educate and raise awareness and encourage a bit more responsibility amongst people. I don’t 100% know what the solution is to that, like, do you have a sign at the foot of the mountains telling people to take their litter home? Should there be more fines in place for littering?

I think it’s great that more people do want to be outside. It’s really important for people’s mental health and well-being to actually get some exercise and be outdoors and enjoy it. But at the same time, there does need to be education. To look after these places and not just take them for granted, because if we can’t even do the basic, simple stuff like taking home our own banana skin, how are we supposed to start making changes that impact the much bigger issues at hand like climate change?

Which actually brings me to my next question. I think everyone in the outdoors is feeling the effects of climate change more acutely this year than than ever before. Incidents like the Marmolada glacier collapse, rockfalls on Mont Blanc and wildfire in Oliana, for example, have brought it to the forefront of a lot of climber’s minds. How can we as climbers, and the wider outdoor community, act upon that to facilitate change?

I think governments and big industry corporations have done a very good job at getting everyone to point their fingers at each other when it comes to climate change. It’s very easy to say you flew here and you’re not vegan or you don’t have an electric vehicle. The reality is that everyone is not going to just stop flying, but I think climbers are becoming more aware and being a bit more careful about how they travel and how often they travel.

And whilst yes, people within the population can make small changes themselves, it is going to take a lot of governmental and industrial change. And that means protesting and writing to your local MPs and getting involved in things that can be done within your area and with organisations like Protect Our Winters. We’ve got COP27 coming up very soon, so holding each country’s government up to to the promises that they’ve made, being aware of your local MP and what they’re voting on and questioning those votes.

I really advocate for people who love the outdoors to go and do the POW Carbon Literacy sessions too, because they are really, really valuable. They teach you a little bit more about what’s going on and what you can do.

I think governments and big industry corporations have done a very good job at getting everyone to point their fingers at each other when it comes to climate change

© Marc Langley

It’s important to get people to stop finger-pointing at each other and to be more of a collective voice, and then using that collective voice to get people that are actually in powerful positions to act upon that

With the state of the environment, cost of living crisis and all the other issues at play in the world, it’s very easy to feel powerless – even defeated. How can we as a community remain positive and proactive in looking after the places we love, and the environment more generally?

It’s important to remember when you feel like that, that change is possible. Like if you look at the ozone layer, it’s possible to reverse the effects of climate change, or at least slow them down.

It’s important to get people to stop finger-pointing at each other and to be more of a collective voice, and then using that collective voice to get people that are actually in powerful positions to act upon that.

I know a lot of people are feeling quite like pessimistic and like their individual actions aren’t going to make a difference – if you’re getting to the point where you’re feeling like that, it’s really worth looking for groups to get involved in. When you’ve got that little community of people that care about the same things as you, you bounce off each other and it reinvigorates that need to do something. It’s a really good way to go about counteracting that feeling.

The Big Issue (E9 6c) at Bosherston Head, Pembroke. © Lena Drapella

You can learn more about Yvon Chouinard’s Clean Climbing manifesto here. For more about Emma, her incredible ascent of the Big Bang and her thoughts on issues such as Black Lives Matter, check out this interview.

Don’t miss a single adventure

Sign up to our free newsletter and get a weekly BASE hit to your inbox

Other posts by this author

Story • Hannah Mitchell • Jul 28, 2023

Reframe, Engage, Create Change

How Arc'teryx's ReBIRD program is engaging consumers with the concept of circularity in the outdoor clothing industry

Story • Hannah Mitchell • Jun 27, 2023

The UK’s Best ‘Almost Wild Camping’ Spots For 2023

Back-to-basics camping and wild vibes... but with a few added comforts

Interview • Hannah Mitchell • Jun 13, 2023

Chasing The 14: The Kristin Harila Interview

In conversation with record-breaking Norwegian mountaineer and Osprey ambassador, Kristin Harila

You might also like

Photo Essay • BASE editorial team • Mar 18, 2024

Hunting happiness through adventure in Taiwan

BASE teams up with adventurer Sofia Jin to explore the best of Taiwan's underrated adventure scene.

Story • BASE editorial team • Nov 21, 2023

Five Epic UK Climbs You Should Try This Winter

Craving a snowy mountain adventure? Inspired by the Garmin Instinct 2 watch (into which you can directly plan these routes), we've compiled a list of five of the best for winter 2023-24!

Video • BASE editorial team • Jul 04, 2023

Zofia Reych On Bouldering, Life And Neurodivergence

Climbing is a driving force in Zofia's life, but for a long time, it also seemed to be a destructive one