Home Story Notes From The North

Notes From The North

Feature type Story

Read time 9 min read

Published Nov 05, 2021

Author Sofie Agger

Photographer Sofie Agger

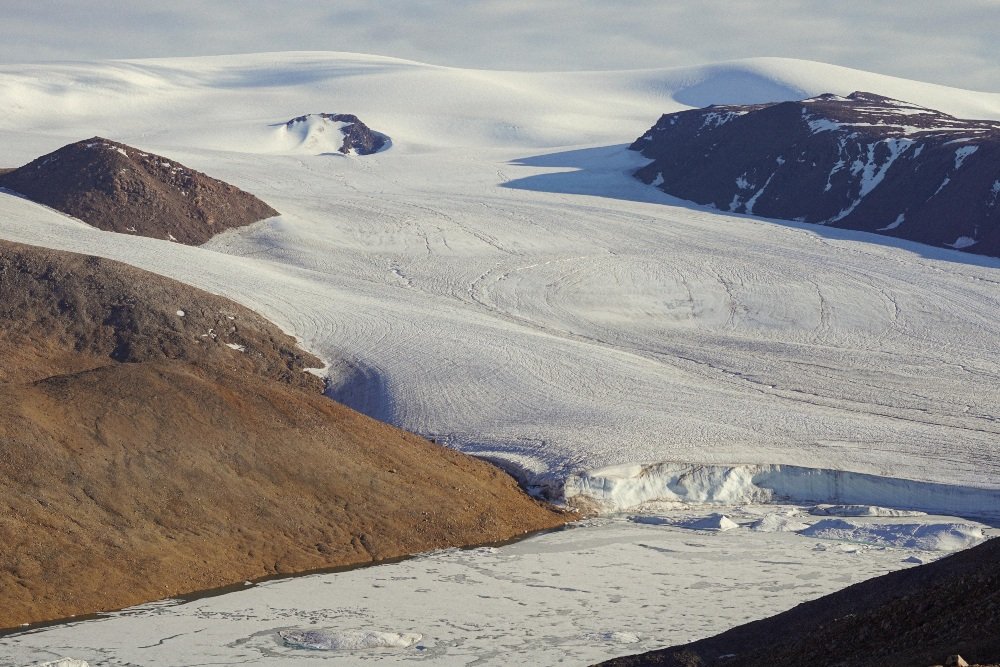

The Arctic is a vast, remote, and mystical place. With all its ice, snow, and frozen ground, it helps keep the Earth’s climate in balance; effectively acting as a reservoir for cold. However, anthropogenic climate change has caused the Arctic to warm significantly over the past several decades; in fact, twice as fast as the global average. The impacts of this warming are critical, and the consequences of rapid glacier retreat, sea ice melt, and permafrost thaw cascade through the delicate Arctic ecosystem; upsetting the Arctic energy balance and fuelling positive feedback loops that can further accelerate warming. But what happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic. Change here has global reach, causing sea-level rise and extreme weather events in distant parts of the world, and highlighting the importance of understanding and tackling this issue.

One of the most important ecological responses to climate change is that the Arctic is getting greener, as vegetation responds to warmer temperatures by growing bigger, taller, and into higher elevations and latitudes. At a long-term research site on the east coast of Ellesmere Island, Canada’s northernmost Arctic island, ecological studies focused on quantifying and understanding the effects of warming temperatures on tundra ecosystems have been conducted since 1980. The research at Alexandra Fiord – or Alex, for short – is run by Dr Greg Henry from the University of British Columbia, who has spent nearly every summer there for the past 40 years. In the early 90s, Greg set up a series of warming experiments and climate stations at Alex as the first site of the International Tundra Experiment. A collaborative network of scientists from 10+ countries at 20+ Arctic and alpine sites, ITEX has played a critical role in forming the understanding we have today of the tundra ecosystem response to environmental change.

I’ve been involved with Greg’s Tundra Ecology Lab at UBC for the past 5 years, through my undergrad initially and now my master’s. This is my third summer at Alex, and the rest of the lab group is a mix of new and old faces: Emily and Lara are also doing their master’s; Will is one year into his PhD; Signe is a postdoc from the University of Copenhagen, and Greg is – well, Greg is the Fiord Lord.

Night after night we trade precious sleep for glacier hikes, walrus watching, boat rides, ocean dips, iceberg climbing, campfires, and intertidal walks. We soak up every second of it

What was supposed to be a three-and-a-half-month field season was cut down to two weeks, and we have a lot to do. While some of us start unpacking the plane – food, scientific equipment, first aid kits, radios, repair supplies, rifles for polar bear safety, and a million warm layers – others start opening the buildings back up and getting settled in.

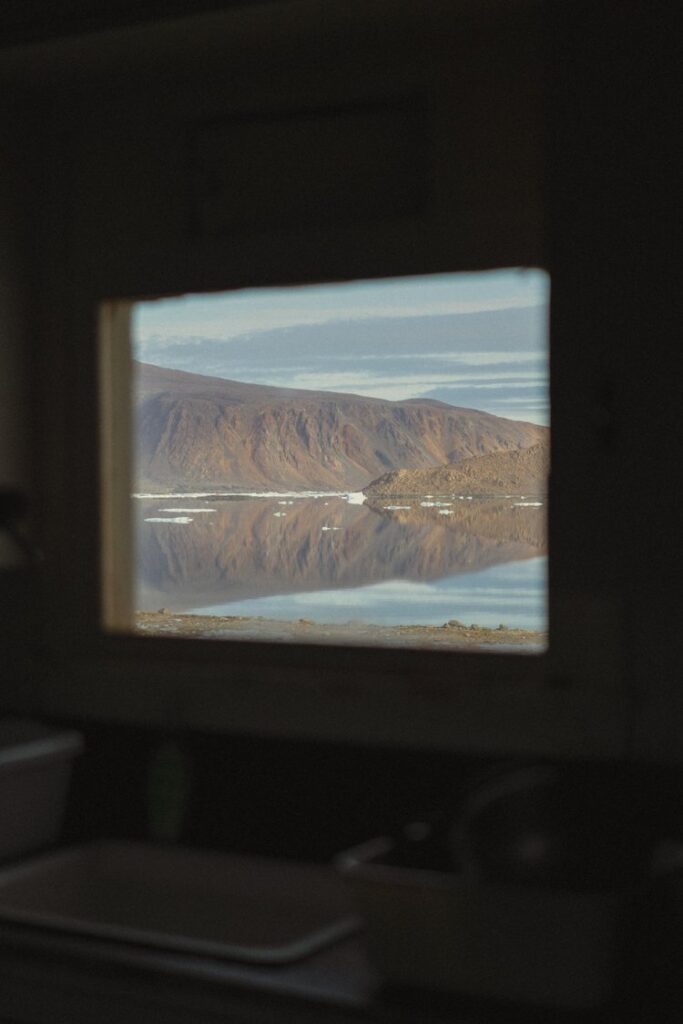

The research base at Alex was originally the site of a Royal Canadian Mounted Police post; established in 1953 with the intention of building a small community, by relocating Inuit families, to help assert Canadian sovereignty in the North. These plans – a dark reminder of the injustices, historic and ongoing, suffered by the Inuit, First Nations, and Metis people at the hands of the Canadian Government – were eventually abandoned, and the detachment was closed in 1963. The five buildings are now just used seasonally by the Tundra Ecology Lab; otherwise, the only visitors are the occasional polar bears who decide to smash their way inside.

The first few days in the field we dedicate to site visits and repairs, and downloading data from the climate stations. The ITEX warming experiments set up in the early 90s were the first of their kind: the open-top chambers made of clear plexiglass function like little greenhouses, warming the air by 1 to 3˚C to simulate the temperature increases projected by climate change models. For the past 30 years, the response of vegetation to warmer temperatures has been monitored in these plots. At the same time, solar-powered climate stations across the valley and small data loggers in each plot have measured things like temperature, solar radiation, snow depth, and wind. With these instruments, it has been possible to maintain a continuous record of the climate conditions at Alex since the 1980s, in parallel with detailed ecological observations.

The long-term studies at Alex have shown significant increases in temperature, shifts in the timing and characteristics of vegetation growth and reproduction, changes in plant community composition, and taller and larger plant growth. Each of our individual studies use the warming experiments to investigate tundra ecosystem response to environmental change, but there is variety in the questions we are asking, the tools we are using, the species we are interested in, and the scale at which we are making observations.

I use a combination of satellite imagery, standard digital photographs, and plant and climate data to analyse patterns and drivers of ‘greenness’ over time in the High Arctic region and at Alex; Emily measures the growth rings in Mountain Avens, a small Arctic shrub, to reflect on past environmental conditions and see if warmer temperatures have increased their growth; Lara measures plant traits like height, leaf surface area and weight, and nitrogen content to explore plant growth and nutrient-use in different plant communities in a warming climate; Will uses a machine that monitors the carbon dioxide fluctuations of key plant processes to better understand how carbon flow within Arctic ecosystems is changing; Signe uses snow manipulation experiments to explore how tundra plants, specifically Arctic Willow, will respond to the increased precipitation and moisture that are predicted for high northern latitudes; and Greg is basically the backbone of it all, running the long-term experiments and climate stations, guiding us through our projects, and collaborating with other researchers all over the world.

We all slip into a daily routine pretty quick. Early mornings are spent around the kitchen table, eating oatmeal, drinking coffee, and setting work goals for the day. Our days in the field are long, busy, and physically demanding, often in challenging and rapidly changing weather conditions. High winds and freezing temperatures are not uncommon – even in the summer months – so wool layers, Gore-Tex, and thermoses of hot tea are our best friends. When we head back to camp in the evening, we take turns cooking dinner while the others do dishes, sort samples, back up data, strum on the guitar, play cards, and read.

One of the advantages of working so far north is that you aren’t limited by daylight in the summer – the sun doesn’t set, it just circles the sky. This is great news for us and our work-play balance because Alex happens to be one of the most beautiful places on Earth, and the midnight sun makes for many late-night adventures and activities. Night after night we trade precious sleep for glacier hikes, walrus watching, boat rides, ocean dips, iceberg climbing, campfires, and intertidal walks. We soak up every second of it.

By mid-August, we had wrapped everything up and it was time to say goodbye to our little polar oasis. Our two-and-a-bit weeks at Alex felt like two minutes and two years at the same time. Tundra time is just… different. It could be the midnight sun, the lack of sleep, or the fact that we packed three months of work into two weeks – it probably all comes together to completely warp our sense of time up there. But while we were busy running around the tundra, the weather had gotten colder, the sun had been pulled further down towards the horizon, and the bright reds, oranges, and yellows of late fall had taken over the landscape.

Being ‘evacuated’ this late in the season can sometimes be a little dicey, and more often than not, things don’t go according to plan. This year, a thick fog rolled into the fiord and delayed our departure by a couple of days, which we took advantage of to soak in our surroundings and prepare the buildings for winter. I don’t think we would have minded one bit if we had been stranded for a couple of extra weeks.

When the plane finally did arrive, we loaded it up with all the equipment we brought and the samples we had collected. The weather was clear, and we were treated to a spectacular flight south across Ellesmere, with jaw-dropping views of the vast and vulnerable region we’re working so hard to understand and protect. Just two days of travel and eight pit stops later, we were snapped back into the reality of life down south. As we each dive into hours of preparing samples, analysing data, and trying to make sense of it all in the grand scheme of Arctic environmental change, we’re inevitably counting down the days until the next venture north to Alex, the little slice of polar paradise at the top of the world.

— — —

To ensure that the six person strong research team were in a position to carry out their research while fully incubated from the elements, Norse Projects developed a uniform wardrobe system that would be adaptable enough to ensure full weather protection for the field and maximum comfort for the down times at the base.

With the arctic environments’ demand for a utility focussed wardrobe that could survive the elements, the team were suitably equipped to overcome extreme winds and freezing temperatures. A carefully constructed layered outfit was defined to ensure that protection for all the challenges face was provided. Interior warmth and comfort was provided through the use of Norse’s essential Niels Standards, brushed lambswool knits and the classic Norse beanie. Further midlayer insulation was ensured through the Otto Light WR which provided the researchers with modular, lightweight primaloft insulation for the ability to adapt if temperature dropped further. Finally, external wind, cold and rain protection was guaranteed through the application of the Rokkvi 5.0

Don’t miss a single adventure

Sign up to our free newsletter and get a weekly BASE hit to your inbox

You might also like

Story • Carmen Kuntz • Mar 24, 2023

The Missing Lynx: The Return Of Slovenia’s Big Cat

Hunters are the reason that lynx roam the forests of Slovenia again

Story • Carmen Kuntz • Mar 06, 2023

How Innovative Nature Conservation Is Making a Big Difference in Armenia

The people behind the ECF project - protecting wildlife and supporting local communities in the South Caucasus

Story • Jessie Stevens • Jan 03, 2023

Bikes For Protest: Not a Hero’s Journey

An exploration of bikes as a tool for protest in light of the climate crisis