In rural Armenia, an innovative, community-led project called the Eco-Corridors Fund for the Caucasus (ECF) is demonstrating that economic growth, tradition, culture and nature conservation can go hand-in-hand.

Working closely with rural communities in protected areas throughout three ex-Soviet countries, the ECF aims to create ecological corridors that facilitate the growth and survival of native flora and fauna, whilst supporting the people that live there to manage the landscapes for themselves. Carmen Kuntz talks to two of the men playing an integral part in the ECF’s work, discovering just why this conservation project is so unique.

The original interview with Garnik Gevorgyan was translated by Armen Shahbazyan.

© Eco-Corridors Fund

From the dirt road that leads into the village of Artavan, it looks like any other rural Armenian village. Rudimentary stone and brick houses clustered together, fruit trees and makeshift chicken coops pressed between buildings, all encircled by fenced pastures with the wind whipping through the golden grass. Trees and bushes overlap, forming a blanket of green that flows up the steep flank of the mountain ridge stretching along the horizon. Brick-red cliffs part the sea of green and rise up to kiss the bright blue sky, like a blushing giant watching over the village below.

This is Armenia. An ageless land where past and present are woven together. The landscape is rugged, rich with mountains, lowlands, lakes and caves. Ancient churches scatter the countryside, monuments to the world’s first Christian nation. During the three-hour drive from the nation’s capital, Yerevan, to the village Artavan the countless villages and towns have similar characteristics and colours – all awash in a thousand shades of tan, taupe, beige and dusty red of the mountains. But a closer look reveals features that make Artavan different.

The dusty road that winds into the village isn’t bumpy at all, almost smoother than the old asphalt roads of Armenian towns and cities, making the drive into the centre of the village a pleasant cruise where the colours and textures of Armenia can be absorbed. Streetlights are rare in rural Armenian villages, yet a handful of them stand on the dusty street corners like sentries awaiting their night shift. The hay meadows that skirt the village are not unusual at all – a necessity to feed livestock through the cold winters. But the outermost meadows stand out, where lush, deep green grass is dappled with yellow, white and purple wildflowers. This patchwork quilt of cultivated and wild fields is another characteristic that makes Artavan unusual.

And perhaps most obvious of all are the small camping tents just barely visible through the trees and shrubbery dividing one field from another, where a couple are untying hiking boots and taking in the panorama from the vestibule of their tent. Tourism is a growing industry in Armenia, but Artavan is far from the touristic hubs.

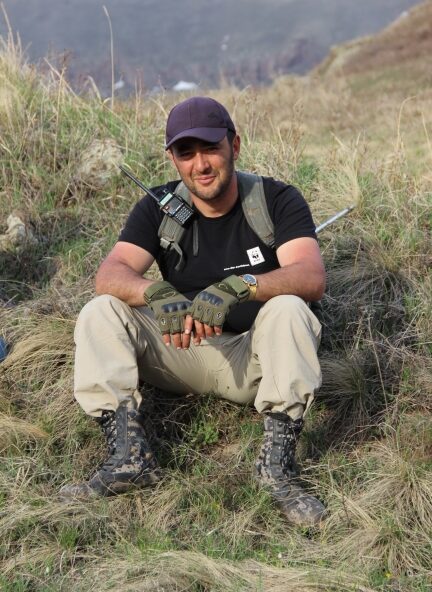

A dark green 4×4 jeep is parked on a side street, and two men stand by the open door, deep in conversation. Pausing to gesture and look up at the mountains, Garnik Gevorgyan is dressed head-to-toe in camo, giving the appearance of a local hunter. But his burly stature and thick hands give him away as a farmer. Armen Shahbazyan leans on the hood of the car, his pleated pants and dress shirt a giveaway that he just arrived from Yerevan, but his relaxed posture and now dusty elbows illustrate that he is accustomed to village life.

These two men are part of the reason Artavan has streetlights, wildflower fields and tourist tents and every house has a solar water heater. Armen is the National Coordinator for an innovative nature conservation project called the Eco-Corridors Fund for the Caucasus (ECF). Funded by Germany and managed by WWF Caucasus, the ECF works closely with the national ministries as well as local and regional governments of Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, the three South Caucasus countries where it has operated since the project’s launch in 2015.

ECF caretaker Garnik Gevorgyan © Eco-Corridors Fund

Collaboration between conservation projects and government is not uncommon in this region, but this is where the similarities between ECF and conventional nature conservation projects stop. The primary objective of the ECF project is to create ecological corridors that connect protected areas throughout the three ex-Soviet countries. But rather than imposing rules, restrictions and no-go-zones, they work with local communities to support them in managing their resources and landscapes in a way that benefits both nature and humans. Locals are provided with funds to manage their lands sustainably, while maintaining full decision-making power and providing opportunities to improve their socio-economic situation.

‘Garnik’s story is one that really illustrated the impacts of the ECF program,’ says Armen. ‘When we met him, he was planning to migrate to the Russian Federation, seeking a better paid job and to take better care of his family’s needs. After ECF launched its activities in Artavan, Garnik was hired to work as a wildlife caretaker and very soon became an important part of the project. He carries out the monitoring of wild animals, provides information to the locals about the project, escorts hiking groups, and manages a tourist camp.’

Although Garnik is just one of two wildlife caretakers now working in Artavan and the neighbouring village of Saravan, the work he does illustrates how ECF works towards simultaneously protecting nature and improving economic wellbeing. By closely monitoring key wildlife species that attracted the ECF to the region, he helps the local community-based organisation use ECF’s active landscape management practices. The result is a ‘living landscape’, providing habitats and corridors large enough to sustain healthy populations of plants and animals without impeding local economics and traditional ways of living. This interconnected mosaic of managed and unmanaged habitats provides diverse ecosystem services throughout all three countries. For biodiversity to be maintained, it needs to be preserved inside and outside protected areas and that is ultimately what the ECF is working towards.

Locals are provided with funds to manage their lands sustainably, while maintaining full decision-making power

© Eco-Corridors Fund

The Artavan camp © Carmen Kuntz

© Nika Tsiklauri

Using methodologies borrowed from successful community-based conservation projects in Latin America and elsewhere in the world, the ECF supports biodiversity through contractual nature conservation, where the community takes the lead. What does this look like on the ground in a village like Artavan? First, ECF staff like Armen work in cooperation with WWF experts using remote sensing and field data to identify ecological corridors based on regional conservation priorities, target species and habitats. Then, a methodology called the Financial Participatory Approach (FPA) builds the motivation and organisational capacity of the village to become a partner in the ECF project, mobilises traditional and local knowledge, and develops trust and partnership with the community. This participatory process uses financial incentives to prompt the community to come up with their own ideas, projects, initiatives, or business ventures that work toward the goal of the ECF.

‘Within the Eco-Corridors Fund project, there is no separation of the community and the land, says Armen. ‘In order for locals to buy into conservation ideas, they have to own the ideas – they have to generate the ideas.’ It was through the FPA process that Garnik was introduced to the project. And also, how the community was able to improve their roads – and with it, accessibility for visitors.

Walking through the village, Armen and Garnik duck under the blossoms of fruit trees that dangle over the stone walls that line sections of the street. They jump from discussing how the village has changed since working with the ECF, to plans for the future. To create and expand eco-corridors, long-term commitment is needed and this comes in the form of ‘conservation agreements’, the other primary methodology used in the ECF. A conservation agreement is a binding conservation contract that the community creates in collaboration with ECF staff. After establishing clear and attainable conservation objectives over a long term (up to 10 years), funding is then provided to the community through the organization to sustainably manage their land and protect biodiversity.

Like many ex-Soviet countries, nature conservation in Armenia has been characterised by focus on strict nature protection through reserves and national parks. Local habits, traditions and livelihoods were seen as an obstacles to biodiversity conservation and locals were limited in the use of their natural resources. Even where local communities benefit from protected areas, e.g. through tourism, this approach has led to conflicts between protected areas and locals and to apprehension against new protected area proposals.

© Garnik Gevorgyan

This rich landscape is where the human, plant, animal and ecological systems of Europe and Asia interact

The ECF takes a community-led approach to conservation, there should be no loss in income or negative effect on livelihoods. The wildflower fields in Artavan are an example of this. To the tourist’s eye, the fenced in meadows look abandoned, as if the community doesn’t have time to tend to them. But Garnik and Armen know that these fields are intentionally kept to make hay later in the year. The hay is needed to feed cattle during the harsh winters, increasing their productivity and keeping them away from pastures. At the same time, some of the more remote pastures are left for wild ungulates. They also act as a reminder of the compromises the community is making to ensure wildlife also thrive. Both hay meadows and abandoned pastures are part of the management plan of a conservation agreement, with ECF providing financial compensation for the ‘hay making’ and the ‘lost pastures’.

‘The community can then use the money to launch new economic activities,’ says Armen. ‘And at the same time, they protect biodiversity which creates a very positive feeling and sense of pride.’

Pride is a strong sentiment in this part of the world. At the crossroad of Eastern Europe and Western Asia, the Southern Caucasus Region is a biodiversity hotspot shared by Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Iran, Russia and Turkey. The Greater Caucasus mountain range stretches between the Black and Caspian Seas with the Lesser Caucasus Mountains range running parallel further south. The landscape is composed of high mountain ecosystems, deep gorges, forests, wetlands, steppes and semi-deserts with drastic variation in altitudes – from sea level to 4,000-meter peaks. With this variety comes an array of climatic zones and thus a unique variety of species. This rich landscape is where the human, plant, animal and ecological systems of Europe and Asia interact, creating landscapes of origin for many domestic plants, farming practices and legends.

The packed dirt street gives way to the field, and the men wander out into the field-turned-campground. A man in a blue cap rakes freshly cut hay into heaps that are scattered amongst the camping tents, and songbirds pick at the seeds. This blend of traditional agricultural practices, modern eco-tourism and wildlife is yet another depiction of the project in action. At the foundation of the ECF project is the creation of wildlife corridors and the protection of nature. So, part of Garnik’s daily routine as an ECF wildlife caretaker is monitoring key wildlife species, which in Armenia are bezoar goats, Armenian mouflon, brown bear and the Caucasian leopard. ‘My day usually starts with waking quite early to monitor animals inside our community conservation area,’ says Garnik. This could mean looking for tracks and signs of animals, using binoculars to spot mouflon and goats on rocky outcrops, or checking camera traps for new photos. He then records all his observations onto an app that allows ECF team to access data from the office. The remainder of his day is then spent either engaged with guiding and eco-tourism activities or community outreach and coordination.

Garnik was trained by WWF specialists to work as a caretaker and also received training on communicating with locals and visitors. ‘Part of the job we do as caretakers is working with locals, explaining the reasons for conservation – why it’s important and what kind of efforts we should make to protect biodiversity,’ says Garnik. He says working with locals to change perceptions of nature conservation is one of the most challenging parts of his work. Even more challenging, dealing with poachers. This can be delicate work. ‘We implement regular patrolling in the community conservation area which we established together with ECF, and if we see illegal activities we report to the appropriate person, police or inspectorate,’ he says.

Using key species to measure the success of the project is a tangible way to tell if the efforts are working. ‘In my opinion, the most exciting outcome of the ECF project so far is the success in biodiversity conservation,’ says Armen. As a national coordinator, he has access to data from all the ECF caretakers. ‘Since 2018, when we signed the first conservation agreement in Armenia, the number of bezoar goats in ECF supported areas has increased from 195 to 535. Leopards have returned and two are permanently living in the area. And the number of brown bears has increased from 14 to 56. This is a great success and creates a lot of excitement among the local communities.’

But the role of ECF is not just to secure biodiversity conservation by safeguarding the ecologically significant species and their habitats, it is also to maintain local culture and improve the economy.

The improved road and streetlights were one of the first tangible results of Artavan’s cooperation with ECF. After successfully completing the FPA process, the community chose to install street lights to deter wild animals from entering the community, thus decreasing negative interactions with wildlife, specifically carnivores. These lights make it less appealing for wolves and foxes to roam through the village, protecting chickens and livestock but also deterring deer from household gardens, and bears from nearby beehives.

The Artavan Campsite is another positive addition to the village, with a cascade of positive effects. The establishment of the conservation area demonstrated the capability of the community, which in turn attracted other projects and other funding sources, enabling the community to develop tourist activities and infrastructure such as the campsite. This is the positive feedback loop ECF strives for, when protecting nature improves socioeconomic conditions, that in turn protects nature.

Hay fields around the Artavan camp © Carmen Kuntz

© Nika Tsiklauri

The camp has also served as an attraction for hikers. Garnik guides guests on day trips or multi-day trips, mostly tourists from Germany, France and UK. The campsite has also become an established rest point for the TransCaucasus Trail, a 3,000km long-distance hiking trail which follows the Greater and Lesser Caucasus Mountains connecting roughly two dozen national parks and protected areas in the region. Artavan is part of the Vayots Dzor section of the trail, a 181 km or 8–10 days segment.

For those visiting by car, or looking for day trips in the region, the Noravank Monastery is a frequent stop. Said to have once been a major religious and cultural center of the country, the medieval monastery built in the 12th century is made of massive red blocks, which camouflaged the church into the extraordinary brick-coloured cliffs the flank narrow gorge of the Amaghu River. This gorge is also part of an ECF supported community conservation area, boasting the highest concentration of bezoar goats and leopards in the region.

The nearby Noravank Bird Caves are another point of interest, where a guided tour leads guests through karst caves where placards offer English descriptions of ancient remains of humans and tools that date back to the various stages of the Copper and Stone Ages.

Bezoar Goats © WWF

© Carmen Kuntz

Even with the many success stories of ECF projects in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia, there are still many challenges the communities face. With an increase in tourism dollars comes the challenge of ensuring the economic benefits are distributed evenly among the community. Many locals that are not directly involved in the ECF work have come up with entrepreneurial ideas of their own. ‘There is honey for sale and people offer home-made food like cheese, bread, vegetables,’ says Garnik. ‘It is popular with tourists as it is organic, home-made and cultural.’ Ensuring the growth of the community is sustainable, environmentally, socially and economically is important to ECF. They are able to identify communities with the capacity and motivation to protect nature while ensuring the impacts of the project are long-term, and don’t end when the ECF support ends.

Back at the jeep, Garnik and Armen shake hands before Garnik departs to meet with a group he will guide on a bird watching hike. The challenges Garnik faces are less theoretical and more tangible. ‘The biggest challenge as a caretaker, is public education and getting the local population on your side,’ he says. ‘Helping the local population not just to become informed, but to become active conservation partners,’ he says.

Garnik interacts daily with the wildlife, locals and tourists, the three groups that form the foundation of the ECF programme, emphasizing the importance of the role he plays in protecting the biodiversity of his homeland. ‘There is a message that I try to deliver to people through my work, and that is that we are not able to exist without nature, but nature can exist without us, so we need to be careful and take care of nature, not harm it and preserve it for us and for future generations.’

For more information on the work that the ECF and WWF Caucasus are doing, check out their website. Want to read about other inspiring conservation projects and whitewater kayaking around the world? Take a look at Carmen’s other features for BASE.

Don’t miss a single adventure

Sign up to our free newsletter and get a weekly BASE hit to your inbox

Other posts by this author

Story • Carmen Kuntz • Mar 24, 2023

The Missing Lynx: The Return Of Slovenia’s Big Cat

Hunters are the reason that lynx roam the forests of Slovenia again

Story • Carmen Kuntz • Nov 30, 2022

Pioneers of Whitewater

The figures behind an adventure tourism movement in southeastern Europe

Story • Carmen Kuntz • Feb 18, 2022

One With The River

Whitewater kayaking and environmental action on Slovenia's Sava River

You might also like

Story • Carmen Kuntz • Mar 24, 2023

The Missing Lynx: The Return Of Slovenia’s Big Cat

Hunters are the reason that lynx roam the forests of Slovenia again

Story • Jessie Stevens • Jan 03, 2023

Bikes For Protest: Not a Hero’s Journey

An exploration of bikes as a tool for protest in light of the climate crisis

Story • Waldo Etherington • Jan 13, 2022

Lessons From The Canopy

In support of time spent climbing trees