As a student at Cambridge University, Alex Bescoby never imagined just where his hunger for history might take him. Now an award-winning filmmaker, author, explorer, historian and Fellow of the National Geographic Society, he has lived on the Thai-Myanmar border studying the shared history of the two countries, explored the back-country of Sierra Leone, the remote Peruvian Andes and the insurgent-ridden southern Philippines.

Alex co-founded Grammar Productions in 2016, an independent film production company with a focus on innovative documentaries that explore the history, politics and culture of diverse and unique societies around the world. His latest project, The Last Overland, saw Alex and his team driving 19,000km from Singapore to London in a 64-year-old Land Rover named Oxford, recreating one of history’s greatest road journeys for a 2022 Channel 4 documentary series and book.

So, how exactly do you go about planning an epic expedition like The Last Overland? I chatted to Alex about organisation, execution and everything in between, from funding a trip to finding the perfect team.

© Léopold Belanger / Grammar Productions

When did you first become interested in the idea of large-scale expeditions like The Last Overland, for example? Were you adventurous from a young age, or was it something that came about later in life?

It was at university, I think. I grew up in Manchester and didn’t travel very much. Even though I sort-of fell in love with tales of great expeditions from the past and I grew up watching people like Michael Wood, Dan Snow, Simon Reeve and Ben Fogle on the TV, I never really thought that I would be able to do that kind of thing.

Then I went to university and I studied history and politics, and I got this accidental scholarship to go and study Thai and Burmese history – it turns out that nobody else would apply for it, so I got sent to Thailand and Burma for three months when I was about 20. It completely blew my mind, it was the first time I had ever experienced a culture shock, and it just opened my eyes to a completely different part of the world with completely different histories than the ones I’d grown up with. I think it was at that point that I realised I wanted to spend the rest of my life travelling the world in some form or another. That really lit the fire.

How did you come up with the idea for The Last Overland?

I eventually moved to Burma, and that became home for best best part of a decade. It was there that I got the chance to do lots more travelling. We were going to places people hadn’t been to in decades. I got this bug, particularly for finding journeys from the past that I could somehow recreate, or following historical stories was what I absolutely loved.

So in combining my passion for history with my passion for travel, it was when I was living in Burma that I stumbled on the story of The First Overland. I was sort-of familiar with it because I grew up in a Land Rover family, and The First Overland is a bit of a Bible for Land Rover fans. I realised that they had been one of the last recorded people to drive across northern Burma and I was absolutely fascinated by the story.

I’d made a few films by this point and was making documentaries for a living, so I had this idea to maybe recreate the Burma stretch of The First Overland, to try and find the road that they driven on because it disappeared into the jungle. And it snowballed really, I ended up reaching out to the guy who owned the car from The First Overland and one of the original team members, Tim Slessor, and they rather called my bluff and said ‘well, you’re not just recreating the Burma bit, you’ve got to do the whole thing’.

For me, what really gets me about any expedition idea is whether it has a historical pedigree and historical depth, whether I can go and learn something about world history from doing that journey.

Oxford on the road to Kashgar, China. © Léopold Belanger / Grammar Productions

What really gets me about any expedition idea is whether it has a historical pedigree and historical depth, whether I can go and learn something about world history from doing that journey

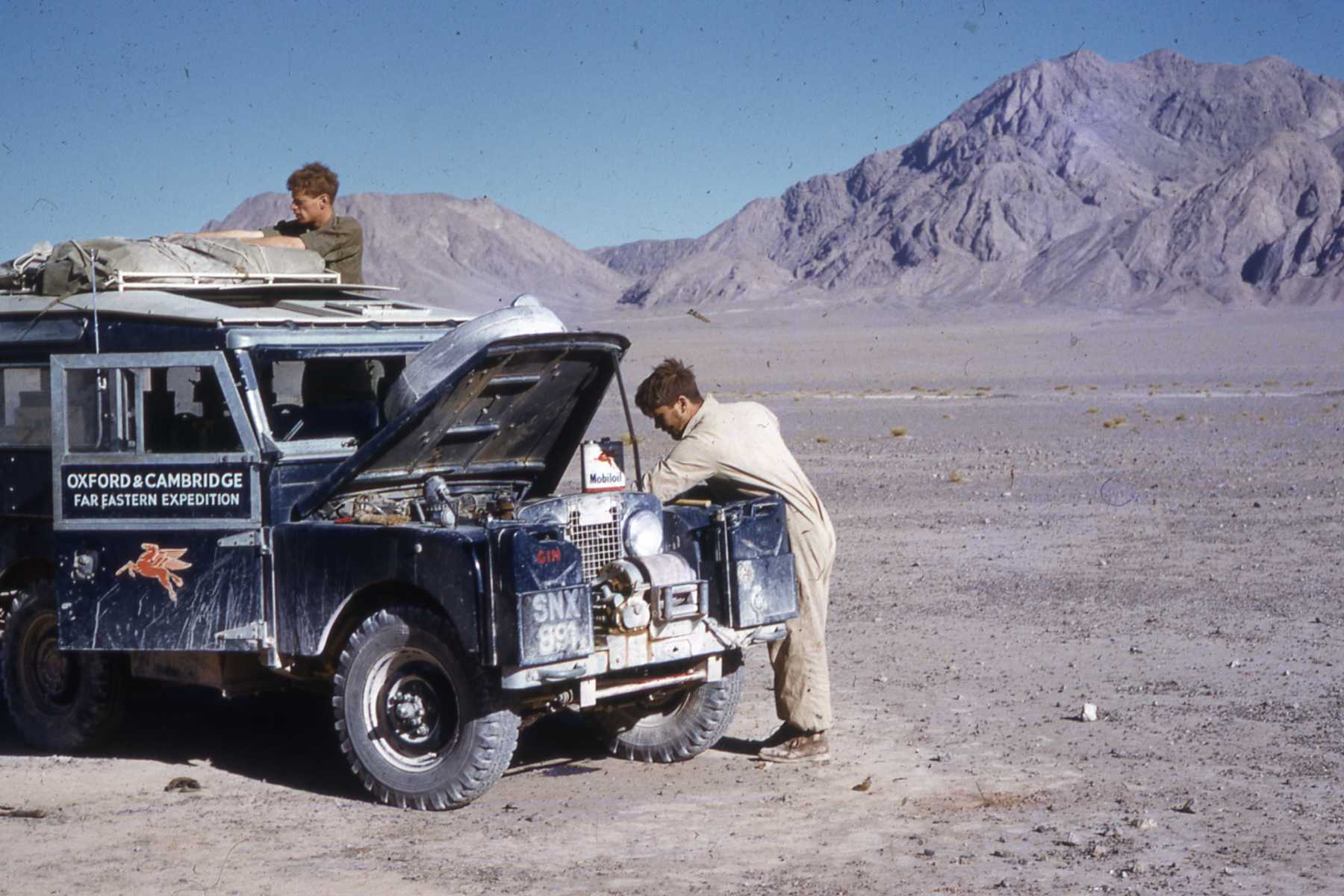

The Land Rover ‘Oxford’ station wagon on its original overland expedition © Antony Barrington Brown / The First Overland

You’ve got to really believe in your story, because the only way you’re going to convince people to fund it is if they can catch the passion from you

How did studying history and politics turn into documentary-making? Was it always something that you thought you would combine with those subjects and where did it all begin?

When I was at uni, I really wanted to join the Foreign Office, that was my dream, this idea of being posted abroad. I came from a very sheltered background, it was a very small town upbringing and I just thought, ok, the Foreign Office must be what you do if you want to go and live overseas. But I didn’t get into the Foreign Office because I think I have a bit of a problem with authority!

I didn’t know anything about filmmaking or writing, I didn’t know any filmmakers. I knew that I wanted to travel. I loved watching travel and history documentaries, I would come home from my job in the city where I was making PowerPoint presentations, and I’d put on the telly and binge-watch Levison Wood, and all these people doing these amazing things and filming them.

It wasn’t until I moved to Burma and I was trying to write a book that I met these amazing characters who became the subjects of my first film – The Last Royal Family Of Burma. I remember sitting there interviewing them for my book, just thinking the whole time, what a waste this will be, that it’ll be in a book that no one will read. So I called a school friend and asked would you mind coming out and filming these interviews, and maybe we can make a documentary? It was as simple as that.

I was working full-time doing another job, and I just started funding this film with every penny I had. And luckily, we won one of the biggest film prizes in the UK, the Whickers Film Prize. We were so, so lucky, and it basically gave us a proper budget and proper professional support to make this first film, I learned how to make a documentary and all of a sudden, I was a documentary maker.

That was back in 2016. Since then, I’ve gone on to make several more films, all with this historical angle but very much about far-flung places with really endearing characters at their heart. That’s my passion. So I’m self-taught in many ways, but also taught by the brilliant people that I’ve worked with. I never thought when I was watching those films of Michael Wood and Dan Snow that one day I might be able to do this for a living, but I got there!

And the rest is history?!

There was a moment where it kind-of snowballed. I remember the first interview we filmed was this this wonderful 95-year-old Princess called Hteik Su Phaya Gyi. My mate Max had been to film school, so he came and filmed it, I’d never been on a film set, never used a film camera before. I slept with the hard drive under my pillow, because I was like, this is so precious. The interview was just golden. I remember thinking, we made this, and it looked like something you could watch on telly. And I was like, ok, right, we can do this!

Oxford alongside the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway

The team recreated images from the original expedition © Léopold Belanger / Grammar Productions

One of the main barriers that a lot of people face when they’re beginning to conceptualise a film like this is funding. What would your advice be to anyone at that stage who is perhaps struggling to know where to begin?

Well, I’ll repeat what many of my mentors said when I was getting into it: Don’t go into documentary making if you want to make a lot of money, because you won’t! But that’s not why you do it. It’s been hardscrabble, but I wouldn’t and couldn’t do anything else. I had a full time job when I started, and I basically moonlighted as a filmmaker. It’s a fantastic industry but it is very hard to make a living as an independent filmmaker, and it’s getting increasingly fragmented.

There are different ways I funded my projects, the very first one was a combination of literally spending every penny I could spare from my own salary, to then winning a film prize, which is something that is very competitive. And the film prize that I won was about ten times the size of the average for a small documentary film. Typically you might be lucky to get two grand, five if you’re lucky, and we won a hundred, which was just insane. So, if you’re relying on things like film prizes, you’ve got to be really good and you’ve got to be prepared to face rejection. Outside of that you’ve got to be inventive about cobbling together sources of money, that’s the trick. You’re never going to fund it from just one source alone.

We also tried crowdfunding which was quite successful but again, you’ve got to have a really compelling story, one that more than just your mum, dad and your neighbours are going to chuck some money into. The film I crowdfunded was about World War II in Burma, and we had an amazing network of families whose whose relatives had served in Burma so we hit a wonderful nerve where people said this story needs to be told.

The Last Overland was funded via brand sponsorship. That was the biggest budget thing I’ve done so far, and the majority of that was from 13 different brands who backed it including OPIHR Gin, a spirits brand that also has a vested interest in the ancient spice route and adventuring. Obviously, all of these pots of money come with strings attached and work and relationships to manage. The one thing we haven’t had as a production company yet is a straight up channel commission, we’ve got The Last Overland on Channel 4 with a mixture of brand sponsorship and distribution funding, so people pre-buying rights and channel money, but all my projects are basically being funded from a mixture of sources.

So I would say my advice to anybody looking for funding, is you’ve got to work bloody hard and you’ve got to really believe in your story, because the only way you’re going to convince people to fund it is if they can catch the passion from you. You can be assured, there are a hundred other people with a good idea who are knocking on the same door.

Alex and Nat on top of Oxford in Eastern Thailand © Léopold Belanger / Grammar Productions

What’s the jumping off point for your planning process? Where do you begin when you’re planning something on the scale of The Last Overland?

With good people. You know, I’m good at some things – I think I’m good at finding a story, I’m good at fundraising. But for a large-scale logistical challenge like The Last Overland, I immediately partnered up with an old friend of mine who had run a travel company, Marcus. He’s not only a dear friend, but also a pedant. Somebody who was passionate about the detail, from fuel consumption, to mileage, to insurance to permits, without Marcus taking that burden and responsibility with a seasoned head and moving people safely in difficult environments, it would never have happened as smoothly as it did. In terms of the filmmaking side, I’m a producer, I know my way around a film set, but you’ve got to bring in professionals, and I had my friends Leo and David who came to run that side of things.

Particularly on an expedition, you’re going to live with these people day in day out; eat three meals a day with them, bunk down with them, wake up with them, get ill, get grumpy, get tired. So you’ve got to be good mates before you go. That being said, sometimes on an expedition, you can’t choose. Sometimes you end up with people and you’ve got to just learn to get on with them. So yeah, people. You can do anything with the right team around you.

What are the other essential characteristics of explorers for a successful expedition?

I’d say the ability to be flexible and realise that your plan rarely will survive contact with reality. When things do change, you have to keep a sense of positivity and enthusiasm, and I guess a commitment or a focus on the end goal. Which is why I think when it comes back to the beginning, it’s about that compelling story for me, story is king. So, everybody who joins this trip has to understand why they’re doing it and what the goal is, and why when it gets really hard or everything feels like it’s lost, they just keep going. A compelling mission is really important.

Oxford embarks on the Pamir Highway, Tajikistan © Léopold Belanger / Grammar Productions

Has there been anything on your travels so far that has totally caught you off guard? Something unexpected that you just couldn’t anticipate, either physically?

One thing we’d obviously talked about was having some sort of major accident. You know, we were driving in a very old car from 1955, we were taking it across 23 countries over four months. And of course, nightmare scenario is it happens in the back end of Nepal or central Tajikistan where where help is far away. We were very lucky that we didn’t have a major collision, we did however, have the wheel fall off the car when it was travelling at 50 miles an hour, which thank god, happened on a flat road in Turkmenistan. If it had happened on many of the mountain roads we had been driving on the previous weeks in Tibet or Nepal, we would have been dead. So there was an element of just how fragile the whole thing was – I think that really caught me off guard. That’s when you have to think, what are we doing this for? If someone died in a car crash for this, is it worth it?

When we were in Nagaland, we got caught in the middle of a very tense standoff between two Naga villages where one had tried to burn down the other the night before. A lot of armed men, a lot of angry people, and we were stuck in the middle of it. And we were skirting Afghanistan and places where tourists had been deliberately targeted by the Taliban and there was again, an element of wondering, what is the right level of risk to take? Where’s the line between adventurous and reckless? I don’t think we ever crossed it deliberately and I think that’s really important. I’m not reckless. I’m not an adrenaline junkie at all, I’m a historian. And whilst everyone came on that trip knowing their own risk appetite and knowing what they were doing, I did feel the weight of it, the responsibility.

Oxford in Tajikistan © Léopold Belanger / Grammar Productions

You can do anything with the right team around you

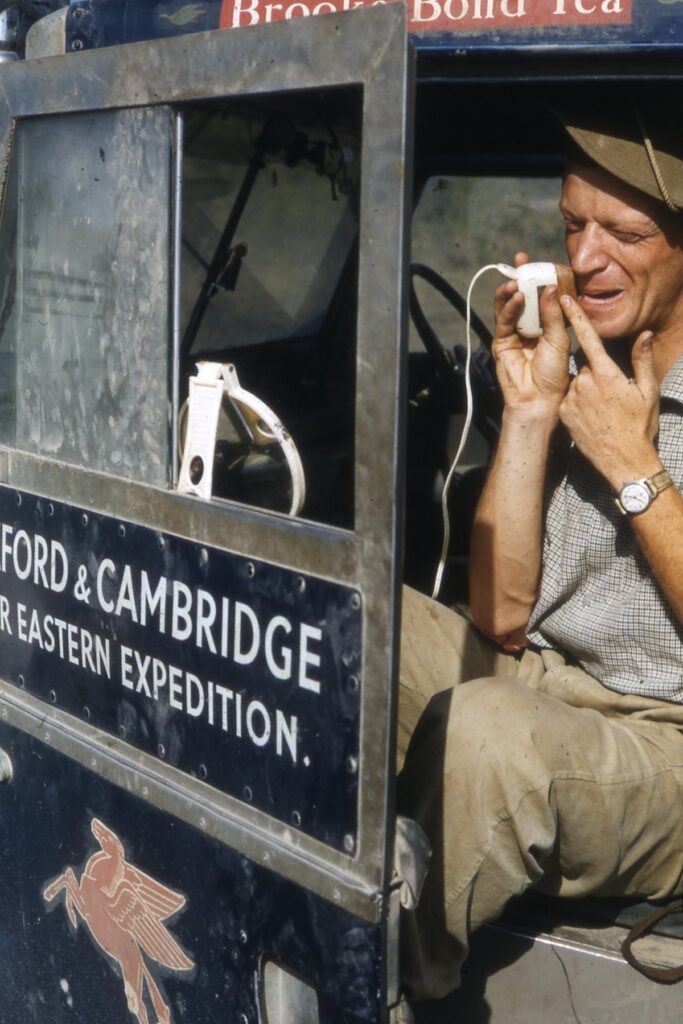

Tim Slessor on the First Overland expedition in 1955 © Antony Barrington Brown / The First Overland

As well as the documentary series, you’ve written a book about The Last Overland expedition. Nowadays, there seems to be a really heavy focus on video, and it can feel like people are loath to read anything longer than an Instagram caption. Do you think people still have a healthy appetite for adventure books?

I hope so. Because frankly, books have a much longer shelf-life, excuse the pun. A well written travel book is something that people will pick up for decades, particularly if there’s something slightly bigger than the journey itself in the story. When I wrote The Last Overland, that was my goal – I wanted people to pick it up thinking it was just a book about a car journey and find out that it’s actually something else.

The First Overland is still in print 64 years later. It’s brilliantly written, and it’s a window into a particular period of time. I wanted The Last Overland to have the same longevity and to be a window in time and not something that becomes redundant within a year. I think a documentary series has maybe five years if you’re lucky, something like Long Way Round or Long Way Down, I think people are still picking those books up. I think if you get the formula right, you can make a series that becomes a classic but it’s much harder because of the sheer volume of content. Whereas I think a book, if it’s thoughtfully done and not just bashed out with what literally happened on screen, it can become timeless.

How do the two production processes differ for you personally? Do you have a preference?

I enjoyed both of them, I was in the edit every day for the series, and I wrote the book myself. With both of them I laughed, cried and wanted to give it all up at multiple points. They’re very different processes but both have their distinct joys. One is much lonelier than the other, a book is a much lonelier exercise but for me it’s very satisfying because it’s something I can do myself. Whereas with filmmaking, I’m reliant on an editor and it’s just completely different because then I’m working with a team – I love that the creative process is different. They’re very different creatures, you learn different things from each one and I like that.

Encountering elephants in Kaziranga National Park, Assam, India © Léopold Belanger / Grammar Productions

Tim Slessor who was part of the original expedition and wrote The First Overland book was a key part of the planning process and inspiration behind your own trip. What lessons did you learn from him that you’ll take with you into future adventures?

What I loved most about the early days of planning with Tim was listening to him talk about what the world was like back then. We’d be looking at maps and he would tell me stories – he spent his life travelling the world and making films and is just an encyclopaedia of wisdom. On the practical side, some of his tips are a bit redundant now because we have new technology and things they didn’t have then, but there’s certain ground rules when it comes to team management, motivation, having good people and a sense of mission. So many of those things that he told me. almost in passing, in those early days came into the fore later on in the trip.

What I learned from Tim, which is why I was so in awe of him, was that he had two undeniable things. One was curiosity – he’s 91, he’s still totally engaged in the news, he’s constantly reading, always wants to know more, always wants to travel more, he’s a guy that just wants to see and see and see. And then something which I think is rare in older men, particularly as we age, is that he’s so open-minded. So progressive, so thoughtful, so willing to be wrong and to learn. And I think that is essential. You know, if you’re going to travel and tell stories for a living, you’ve got to continually be willing to be wrong, to be humbled and to have your mind changed by events and what you find. Those are two qualities that I absolutely adored in him.

The Last Overland is available to watch on demand on ALL4, and Alex’s book about the expedition is available to buy in hardback.

Don’t miss a single adventure

Sign up to our free newsletter and get a weekly BASE hit to your inbox

Other posts by this author

Story • Hannah Mitchell • Jul 28, 2023

Reframe, Engage, Create Change

How Arc'teryx's ReBIRD program is engaging consumers with the concept of circularity in the outdoor clothing industry

Story • Hannah Mitchell • Jun 27, 2023

The UK’s Best ‘Almost Wild Camping’ Spots For 2023

Back-to-basics camping and wild vibes... but with a few added comforts

Interview • Hannah Mitchell • Jun 13, 2023

Chasing The 14: The Kristin Harila Interview

In conversation with record-breaking Norwegian mountaineer and Osprey ambassador, Kristin Harila

You might also like

Photo Essay • BASE editorial team • Mar 18, 2024

Hunting happiness through adventure in Taiwan

BASE teams up with adventurer Sofia Jin to explore the best of Taiwan's underrated adventure scene.

Story • Tom Grant • Feb 23, 2023

Swat Valley Ski School

An impromptu ski lesson during a ski-mountaineering expedition to make the first descent of Falak Sar in northern Pakistan

Interview • Rosie Fuller • Jan 18, 2023

Interview: A Baffin Vacation

Sarah McNair-Landry on her 45-day multi-sport expedition in the Arctic Circle