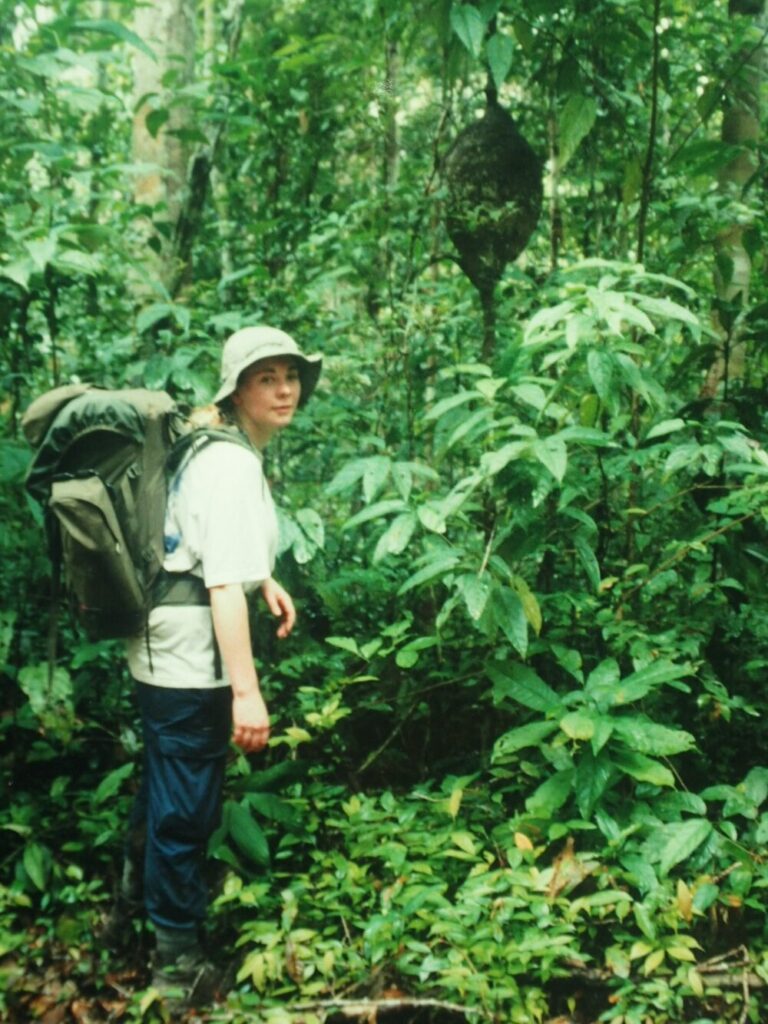

Belinda Kirk has led groups into the wilderness for 26 years. She’s led dozens of international expeditions, walked through Nicaragua, sailed across the Atlantic, searched for camels in China’s Desert of Death, discovered ancient rock paintings in Lesotho and gained a Guinness World Record for rowing unsupported around Britain. In 2009, she established Explorers Connect, a non-profit organisation connecting people to adventure and encouraged 30,000 ordinary people to engage in outdoor challenges – both big and small. In 2020 she launched the first conference to explore how adventure effects wellbeing. In August 2021 she released her book Adventure Revolution, to explain why adventure is essential to our wellbeing, putting forward an energising case for ditching the living room in favour of a longer, happier, and more adventurous life.

Nineteen years ago, everything changed. It was the day I realised that adventure is not a frivolous luxury but a necessity of the human spirit. I was standing in the rain outside the iconic Royal Geographical Society (RGS) in London. During the previous summer of 2002, I had led a group of young people through the Amazon, and we had reconvened to present our findings. Although I’d experienced my own personal transformation as a result of adventuring, I had no appreciation of the kind of impact adventurous activity could have on other people. As I waited, a woman approached me.

‘What did you do to my daughter?’ she asked.

I panicked for a moment, a whole host of scenarios running through my head. There was the girl who’d been bitten by a bat. Could it have been her? Or maybe she was one of the unlucky few who experienced the joy of jungle parasites?

Before I could say anything, the woman gave me a giant bear hug, like we were long lost friends. ‘I don’t recognise her,’ she said. ‘She’s a different girl. She’s so much happier. I can’t thank you enough.’ She told me her daughter was Alice, and then it clicked. Alice had been one of my toughest challenges of the trip. A seventeen year old with low self-confidence and a history of self-harm, Alice struggled – mentally, academically and socially. While most of the team formed fast friendships, when we first set out Alice was distant, she wasn’t connecting well with the rest of the group. So, I gave her a job. I put Alice in charge of the group kit for her team of twelve. It was an important job – and one that would require her to talk to every member of the team. At first, I helped her. I didn’t want her to panic or become more fearful. But little by little, Alice owned the role. I could see she was smart and capable – and eventually, so could she.

A few weeks into the expedition, I visited Alice’s team. I was pleased to discover that Alice had volunteered to be the camp manager, running the day-to-day logistics of their basecamp. The timid girl I had met at the airport just a few weeks earlier was now confidently striding about her jungle camp, arranging water-purification checks, making cooking schedules and assigning work rotations.

From the outside, it was impossible to miss the transformation. The girl who had joined the expedition and the young woman who’d returned to her family in Britain were strikingly different. But I’d never considered how deep a transformation it could actually prove to be – and how long it might last once she was out of the jungle. And yet, six months later, here was her mother, hugging me in the rain, telling me that Alice now helped out at home, had brought her grades up and, perhaps, most importantly, even had a few new friends.

For all my memories of that trip I’ll never forget this one interaction outside the RGS. It seems as clear today as it was the day after it happened. I believe that it’s so seared into my memory because it was the moment I came to fully believe in the power of adventure to change people’s lives for the better.

Adventure changed my life. And for the last twenty-six years of taking others on adventurous activities, I have seen it change people of all ages and abilities, and from all walks of life – seen it turn the timid into the confident, the addicted into the recovering and the lost into the intentionally wandering. The multitude of ways adventure can transform is why it excites me so much. Not just the act of adventuring itself but what it can do for us as human beings navigating our way through the ups and downs of life. This is what I call the Adventure Effect, which lays on a spectrum between deep and permanent transformational change to a less extreme but still impactful shift towards feeling better than before and thinking with a more helpful mindset.

I had experienced a similar change myself decades earlier on my Duke of Edinburgh Award expedition. I was 16 years old old and it was my first overnight adventure. Hiking and camping largely away from adult supervision in the Brecon Beacons, the experience was designed to foster autonomy and build self-belief. As a teenage girl I had suffered from very low confidence. Always feeling too ugly, too fat, too unpopular, never doing well enough in the classroom or on the sports field. This challenging weekend in Wales was a turning point. I found something that made me feel alive but also that made me re-evaluate what I might be capable of. After all if I can climb mountains, camp in the rain, survive the wilds, then what else might I be able to do?

Adventure can build our self-confidence; it can also help teach us how to live our best lives. I first met Freyja in 2015 when she joined a mountain hiking weekend with me in Snowdonia. She came across as one of those people who seemed to have their life sorted. Yet, it turned out, for a long time she had felt lost. At work she had held herself back, too afraid of failing. She’d avoided opportunities to present her ideas to her colleagues, encouraging others in her team to do so instead. She’d been ‘mortified’ by the thought of failing publicly, so she’d simply not allowed herself to do so. However, this had changed after she took up climbing. Now she was leading workshops, standing up in front of her colleagues and strangers, doing more and more outside of her comfort zone. She’d learnt that ‘the more I do a climbing route that scares me, the more familiar it gets. The more I do workshop facilitation, the easier it becomes. I wasn’t pushing myself as much as I wanted to because I was avoiding failure. Now I give myself a pep talk on the climbing wall and in these professional situations too. I think to myself, I’ve got this.’

I’ve been witness to hundreds of transformations like these. Ordinary people going through extraordinary change. They were my inspiration for researching why adventure is so impactful. Now a significant part of my mission is in promoting the benefits of adventure on wellbeing, including in my book Adventure Revolution: the life changing power of choosing challenge. I’ve found a large body of research supporting the idea that adventure has positive effects on wellbeing. For example, according to one study, those taking part in adventurous physical activity go on to have a better quality of life and improved relationships, they achieve more and experience more joy. A recent study by Sheffield Hallam University found that family adventure holidays can lead to improved family communication, trust, and cohesion. And participants in an independent study into women in adventure were noted as saying ‘Adventure has given me the confidence to be myself and live in the present.’ Another said, ‘Being active outdoors has given me self-esteem, a sense of self-worth and confidence like nothing else ever has.’

After all if I can climb mountains, camp in the rain, survive the wilds, then what else might I be able to do?

With all this evidence and inspiration why aren’t more of us answering our call to adventure? I believe it’s because we’ve engineered it out of our everyday. As a society we spend more time indoors than ever before. We follow so many rules and routines. So, to experience and therefore benefit from adventure, we need to make time in our busy schedules to go outside and seek new challenges.

We don’t need huge amounts of time or money to live more adventurously. Everyone can do it, no matter our experience, fitness or age. However, I understand that the first step is the hardest, so my advice is to start small. I’ve taken groups on adventures where I have seen significant positive wellbeing outcomes over a weekend, a day or a night. Join an adventure class or club, camp in your garden, try wild swimming, small steps into a more adventurous lifestyle. Once you start to adventure, the positive feedback you’ll get from participating will empower you to take even bigger steps and lead you to experience even more positive wellbeing.

Don’t miss a single adventure

Sign up to our free newsletter and get a weekly BASE hit to your inbox

You might also like

Story • BASE editorial team • Nov 21, 2023

Five Epic UK Climbs You Should Try This Winter

Craving a snowy mountain adventure? Inspired by the Garmin Instinct 2 watch (into which you can directly plan these routes), we've compiled a list of five of the best for winter 2023-24!

Story • Ed Smith • Jul 26, 2023

Victoria Falls: The Smoke That Thunders

Exploring a personal relationship with the Zambezi and its uncertain future by kayak

Video • BASE editorial team • Jul 21, 2023

Merging Two Lives: The Personal Journey of Hamish Frost

The challenges and triumphs of embracing sexuality in the outdoors