Home Story From Senegal to Somalia: Crossing the Sahel

From Senegal to Somalia: Crossing the Sahel

Feature type Story

Read time 15 min read

Published Jan 05, 2021

Author Reza Pakravan

Photographer Mark Game

Story | Reza Pakravan Photography | Mark Game

Spanning the width of Africa, the Sahel is the ecoclimatic and biogeographic zone of transition between the Sahara to the north and the Sudanian savanna to the south. Home to some of the harshest conditions on the planet, it’s here that the effects of climate change are felt the most and rebel uprisings are common.Having completed several courageous trips across the African continent, Reza Pakravan wanted to document these forgotten frontiers and tell the story of those who live there, whilst setting himself a new challenge.

In 2019, he travelled the full length of the Sahel belt from Senegal to Somalia. Stretching him both physically and mentally like never before, the adventure proved to be his most testing to date. Below Reza describes a few of his highlights from his journey across the Sahel.

Walking in Mali with a local guide.

Trekking in the Dogon country in Mali

Upon arrival in Mali, I followed its beating heart: the mighty Niger river. The Niger is the main source of life for many tribes and ethnic groups who depend upon its waters. After days on and off boats, I finally managed to reach the magnificent city of Mopti, the Venice of Mali and the confluence of the Bani river and the Niger. In Mopti I chartered a 4×4 and headed to the ancient Dogon country, home to one of the most extraordinary tribes in Africa: the Dogon people.

The Dogon country perhaps offers some of the best hiking trails in the world, but climbing sand-washed mountains under the beating sun at the hottest time of the year was no easy task. But we were never short of surprises in the ancient land of Dogon people and all it took was to turn and face the valley overlooking the orange desert, to appreciate its beauty. Trekking along an old path and up and down cliffs, we came across red paintings on the rock wall. It looked like something out of a movie set. My guide explained to me the meaning behind the different paintings and their significance in Dogon mythology. For example, there were many drawings of crocodiles. When the Dogon people escaped Islam and found refuge in this inaccessible land to continue practicing their own religion, it is believed that crocodiles showed the Dogon people where to get water. Ever since crocodiles are considered sacred in the Dogon country.

The villages we passed through, many of them perched on cliff tops, each had a story to tell. Upon arrival, permission from the Chief was needed before entering and we often met him in the village Toguna (a low-roofed structure built with stone and timber and is usually found in the centre of every village). The Toguna is where the Chief and the village elders would sit to settle disputes, the low roof is made with the express purpose of forcing visitors to sit rather than stand, which helps avoid violence when discussions get heated.

As well as Togunas, the villages built on escarpments had mud-built granaries dotted around. The number of granaries indicated the number of women living in the village, for each woman has her own, in which she stores food for her family. Unlike the rest of Mali, women in the Dogon country are economically independent, earning and spending their own money. After a couple of incredible weeks trekking in the Dogon country, I made it to the town of Bandiagara, from where I could hitchhike all the way to the south of Burkina Faso.

Reza meets a Malian hunter defending people against terrorist organisations such as Al-Qaeda.

A funeral in the Dogon country in Mali.

The Sindou peaks

As the sun rose, the faint orange glow blossomed behind a peak, creating a collision of soft-coloured tones which made everything absolutely magnificent

The Sindou Peaks of Burkina Faso

Upon arrival in Burkina Faso, my guide insisted that we detour from our route and visit the Sindou Peaks. I was really skeptical and frankly exhausted from the last few days of trekking in the Dogon country. But I agreed. We entered Burkina Faso at night so I couldn’t see our surroundings. We found a spot and pitched our tents. The following morning, I woke up to an incredible green landscape around me. I couldn’t believe how much things had changed since dry and arid Mali. Around us was lush green surrounded by incredible towers of sandstone with just small passages between them. The place didn’t seem real. As the sun rose, the faint orange glow blossomed behind a peak, creating a collision of soft-coloured tones which made everything absolutely magnificent. I was filled with a sense of happiness and privilege to be there.

Adventure should always start with a cup of strong coffee. I put the coffee pot on the stove and stared into the incredible landscape around us. It was the first time since the beginning of the journey that I experienced calm. A new day had begun.

After a day of hiking through this incredible landscape, perhaps the best I have ever seen, we finally reached Lake Nyoufila, an absolutely beautiful lake with palm trees around it. We finished the day watching the sunset over the lake with the peaks in the distance.

I made my way through the lush green of southern Burkina Faso and then on to arid and dusty Niger, using various means of transport including bush-taxis, overloaded trucks, buses and, of course, traipsing long distances on foot. I camped along the way (and also slept in petrol stations, mosques, hospitals and churches) until my arrival in Chad.

Refugees on their 20km walk back from the Saturday market

Public transport Lake Chad style

Boudouma tribesmen on the shores of Lake Chad.

Lake Chad

In the 1800s, European explorers arrived at the marshy banks of a vast body of freshwater in Central Africa. Because locals referred to the area as ‘chad’, the Europeans called the wetland Lake Chad, and drew it on maps. But ‘chad’ simply meant lake in local dialect. So here it is. Lake Chad, or ‘Lake Lake’.

I have travelled to some far-flung places on Earth, but Lake Chad is the most remote place I’ve ever been. Located right in the centre of the continent, Lake Chad is shared between four countries – Chad, Niger, Cameroon and Nigeria – and millions of people living there do not feel that they belong to any particular nation. It’s one of the largest wetlands in all Africa: 30 million people depend on it to survive. I entered the Lake Chad area from the Niger side. As I was travelling west to east, I had to go around the lake to be able to continue my journey east.

As I stepped into the small town of N’guigmi, all my senses came to life. The smell, the noise, the sights. The streets were nothing but dirt tracks. It felt as if I had stepped back a hundred years. I have been to over 80 countries around the world, many of which are developing nations, but I had never seen anything like this. It was hard to spot a motorised vehicle. Most people simply walked and carried heavy loads over their shoulders. Those richer ones had camels and donkeys. Dressed in their traditional outfits – the women in bright and beautiful colours; the men more conservative – they stomped through the 45ºC degree heat.

The more I travelled, the more I realised that the modern world had not made it here. All over Africa, you see many people carrying mobile phones. In Lake Chad, I rarely saw any.

I began to journey around Lake Chad on the desert track roads. The heat was excruciating. Life in 45ºC degrees is punishing, especially when you’re trying to walk in sand. Survival in such conditions, in such heat, is no easy task.

I visited village after village, using whatever means of transport I could find. The Army controlled the territory, leaving everyone tense and ill at ease. Checkpoint after checkpoint. I have never been in a place where my documents were checked so many times.

Boudouma tribe woman

Wodaabe woman at her house

With a Kanembu family -Lake Chad

In the absence of any public transport, I hitched a lift with a convoy carrying people and goods to make it to Baga Sola, a small town which in its heyday was a hub of trade. Livestock used to be exported from here to Nigeria, local fisherman would sell their catch and islanders came from far and wide to trade their goods.

Villages are formed based on ethnicity. Lake Chad’s largest ethnic groups are the Kanembu, Boudouma, and Bougourmi, distinguished by the variously patterned scars on their faces, received during their initiations. The face of a Boudouma tribesman for example, has one major scar in the centre of his forehead and four scars on each side of their face. These tribes remain some of the most untouched cultures in the world.

I have met many indigenous people around the world and seen the rapid changes in their ways of life by the ever-encroaching imposition of the modern world. I have seen how Amazonian tribes embrace technology, running their campaigns on Facebook, while a simple mobile phone has never made it to Lake Chad. And yet, along the shores of Lake Chad, the tribes have no connection with this modern world whatsoever. Perhaps this should come as no surprise, the region is so remote, so hard to get to, and the lack of infrastructure makes any connection with the outside world almost impossible. Everything is done manually and the lack of access to modern tools is felt especially.

“Technology here is a taboo,” my guide tells me. “People don’t want to change their way of life.”

In the absence of any form of organised public transport, I relied on trucks operated by aid workers to make it to the east of Chad and into Sudan. My arrival in Sudan coincided with the Sudanese revolution: the country was in a state of emergency. I entered via notorious Darfur, finding myself in the wrong place at the wrong time. Upon entry, I was arrested and then eventually kicked out – into Ethiopia.

Abuna Yamata church

Calling the spirits. Zar ceremony in Ethiopia

The Danakil Depression in Ethiopia. The hottest place on earth

Ethiopia : Abuna Yamata Guh – Sky Church

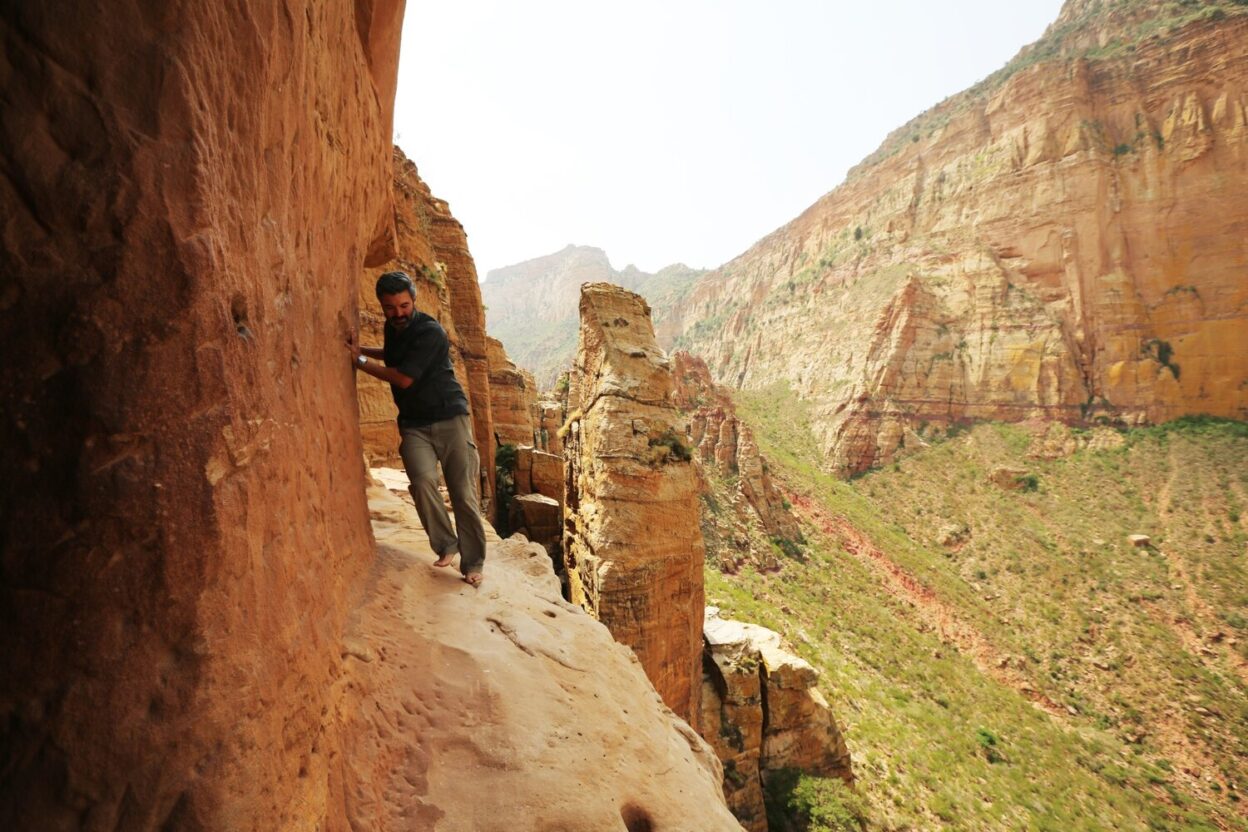

Abuna Yamata Guh is a place I will never forget. Hidden in the remote mountains of Gheralta in northern Ethiopia, Abuna Yamata is a monolithic church built on top of the rocks and carved into the side of a cliff above a staggering 250 metre drop.

The road to the church snakes through the epic Gheralta Mountains. The scenery was beyond description, the mountains featured the most incredible rock formations. We got to the foothills. The road stopped. The climb started.

We started the challenging climb and after 45 minutes we made it to the cliff. A Coptic Christian priest makes this incredible journey there every day, climbing sheer, steep cliffs barefoot and without a rope. While climbing myself, I couldn’t help but think, what must go through someone’s mind to compel them to build a church in the side of the cliff?

When we reached the cliff I was asked if I wanted to climb with a harness or not. I opted for the harness. A hair raising vertical free solo climb wasn’t for me. I started climbing with guidance from the locals. Then the priest arrived and waited a bit while I climbed. Since I was taking so long to climb, he wasn’t having any of it and started to climb up to me using foot holds. He was unbelievably fast and overtook me with laughter and without safety equipment. He had been doing this climb for 40 years though.

With a bit of a guidance, I finally climbed the first wall. The second one followed, which was a bit easier. But then, thinking I was done with the scary parts, I had to endure a ledge on the cliff-face above a 300 metre (980 foot) sheer drop. It was so nerve wracking that I could hardly breathe.

I finally made it to the church to meet the smiley priest. Inside the church was richly decorated with amazing murals that depicted the lives of the nine Saints with well-preserved scriptures from the 6th century written on goat and cow skin were kept in perfect condition, thanks to the low humidity and the shelter from sunlight.

As the sun began to set, I sat on top of the cliff overlooking this incredible landscape, thinking about the experience of this hidden gem in Ethiopia.

While the world’s media tends to focus on war and conflict in the Sahel, my aim was to tell its untold stories, of the people and the traditions that have stood the test of time

Somaliland

Mountains of Somaliland

I left Ethiopia for the last country of my journey: The Republic of Somaliland. A self-declared independent state, though internationally considered only as an autonomous region of Somalia. Most of the country was sparsely vegetated – typical of its semi-arid landscape – and the last thing I expected to see was the mountain range that rose between me and my destination, the Red Sea.

My climbing started from the town of Sheikh, a small mountain town at 1,470 metres, which features the ruins of a British Army base. As I started my trek through the Sheikh mountains, the wildlife – including tortoises, warthogs and beautiful birds – was hard to miss. The temperature dropped significantly as I ascended. Sporadic Somali nomad settlements appeared in the lower elevations, with an abundance of livestock. The only way to refill my water supply was to rely on the nomads. Despite their rather strict culture, the nomads nonetheless invited me to spend nights in their tents with their families.

The mornings were fresh. For the first time on the whole journey, I considered wearing a second layer of clothing. I climbed, and as I gained altitude the landscape became greener and the mountains more scenic. I realised that I had never been so far away from the company of humans since arriving in Africa. In the mountains, there was no one to talk to, nor any paths to follow, only the gentle wind which carried occasional birdsong. On either side of me, sheer drops, hundreds of meters deep, plunged down to the shallow rivers below. I could smell the sea in the distance and, with it, the end of my journey. It inspired excitement, generated adrenalin, and I knew it was time to descend, down to the desert which would lead me to the sea, to finish my 5,000-mile journey across the African continent with a welcome swim in the Red Sea.

While the world’s media tends to focus on war and conflict in the Sahel, my aim was to tell its untold stories, of the people and the traditions that have stood the test of time. An alternative narrative. Mother Africa might be complicated, often difficult, but there is nowhere else on Earth like it. I had seen the most incredible things there but, more importantly, I had met the most incredible people, from a plethora of different races, religions and ethnicities. And yet, despite the differences, I experienced an overwhelmingly common thread connecting us all. That thread was humanity and kindness. We live in an age where we are told to fear difference. But, in the Sahel, I found few things which divided us, and far more which connected us.

Women growing vegetables within the Great Green Wall

Reza meeting Great Green Wall ranger in Senegal at the beginning of his journey

The Great Green Wall

The Sahelian belt, at the southern edge of the Sahara desert, is where climate change has hit the hardest. Millions of locals are already facing its devastating impact. Persistent droughts, lack of food, conflicts over dwindling natural resources and mass migration to Europe are just some of the many consequences.

I saw how Dogon tribes in Mali picked up arms to push Fulani pastoralists – who were forced by desertification to migrate south – out of their lands. In Chad, as the climate has changed, Lake Chad has begun to dry up and the desert encroaches further every day, families struggle to make a living from farming or fishing. This has played into the hands of Boko Haram who, taking advantage of the situation, started to recruit people with the promise of removing them from poverty.

But there is hope here too. The Great Green Wall (GGW) is an ambitious African-led initiative which aims to grow an 8000km line of trees and plants across the entire width of the continent to bring life back to the land and transform the lives of those who remain there. Once complete, the GGW will be the largest living structure on the planet, three times the size of the Great Barrier Reef; a symbol of the hope that humanity can overcome its greatest threats.

During my travels I visited many GGW sites, in various countries, and interviewed government officials behind the projects and UN members. I had an image of the GGW as rows of thick trees across this vast expanse of land but the reality was different. Most of the trees were quite small and mainly consisted of acacias and gum arabic trees – resilient to drought, these are the only ones that can survive the Sahelian climate. Nevertheless, though they were not particularly leafy, they still provided life to the soil around them.

The GGW is not only about planting trees, it is also about land management, improving the quality of soil and making sure that the trees are disease-free. It’s also about resource management.

In many sites, the project was not about planting trees at all (they already had enough) but about preserving what they had. Without this preservation, the local population would cut the trees down and sell the wood as charcoal. So, with the GGW, the land is preserved, the trees are protected, and the wood is cut based on a quota that is given to the people. They can still sell the wood but in a controlled manner. It’s about resource management.

I could instantly see the tangible benefit of the GGW on the wildlife, birds had returned and I could hear them sing. In some countries – including Senegal, Burkina Faso, Chad and Niger – the GGW has made major progress and the local population have started to enjoy the economic benefits.

I was very impressed with the speed of the project around Lake Chad: perhaps one of the poorest and most barren place on earth. I could see how the GGW created employment and how the local population was actively engaged with the project.

The head of the Great Green Wall in Senegal during our interview told me that the future of the project is totally dependent on making a commercial case. This includes selling carbon offset to developed countries and planting trees on their behalf. He explained the effort has been made and that international collaboration across the Sahel and positive results are becoming apparent.

Reza’s new four part adventure series, The World’s Most Dangerous Borders, which chronicles his three and a half month expedition across the Sahel, is available on Amazon Prime Video now.

Don’t miss a single adventure

Sign up to our free newsletter and get a weekly BASE hit to your inbox

You might also like

Story • Kieran Creevy • Jun 16, 2023

Scrambling Before Scran on Scotland’s Misty Isle

Sun-drenched ridge lines with expedition chef Kieran Creevy on the Isle of Skye

Video • BASE editorial team • Jun 02, 2023

How To Clean And Care For Hiking Boots

Our top five tips to give your hiking boots a 'glow up'

Video • BASE editorial team • Mar 30, 2023

How To Break In Leather Walking Boots

5 fast hacks for breaking in your boots, beating the blisters and reducing the ankle rub