Today, feather filled insulated jackets are a pillar of outdoor and adventure clothing but it wasn’t always that way. How far back does the history of the down jacket stretch? Who made the first iterations and how did the garment become common place in the industry? BASE Editor Chris Hunt takes a look back at the genesis of the down jacket, what makes it so good, and how a relatively small player in the feather industry changed the game forever.

Martin Feistl and Amelie Kühne, layered up for a night on the Grossglockner, Austria © Silvan Metz

While the down jacket has now well and truly transcended the world of high alpine mountaineering, there are no prizes for guessing its origin. Perhaps more surprising though, is the geographical location from where that spark of inspiration first came. The icon of alpine clothing actually originates from the hottest and flattest continent on Earth.

The story leads back almost 100 years, to George Finch — a farmer’s son, from a small town in New South Wales who, in the race to be the first person to climb Mount Everest, became rival to George Mallory.

In 1922 he was invited on Britain’s first Everest expedition but the choice was a controversial one. Having moved to Europe with his family, he gained a huge amount of experience, quickly climbing many of the iconic peaks in the Alps. In doing so Finch opted for the more challenging and dangerous routes, earning him a reputation as something of a maverick. Despite the audacious nature of his ascents, Finch was too brilliant not to be invited, and for the expedition, he invented two iconic mountaineering technologies that are still used in the highest mountains today: bottled oxygen and the puffer jacket.

This first iteration of the insulated puffer was bright green and constructed from fabric taken from the shell of a hot air balloon, filled with the feathers of the eider duck. But the design was too unconventional for the gentry of the Alpine Club, as was the use of bottled oxygen and Finch was ridiculed for his creations.

After being seen to repair his own boots – something well beneath the aristocratic classes of the Alpine Club — Finch was ostracised and the expedition banned the use of supplementary oxygen. Colonel Edward Strutt, the expedition deputy leader who’d later become president of the club was heard to remark, ‘I always knew the fellow was a shit’

But Finch’s innovation didn’t go totally overlooked, and eventually his jacket caught the eye of John Noel, the expedition’s photographer. ‘Finch, who had a scientific brain, invented a wonderful green quilted eiderdown suit of aeroplane fabric. Not a particle of wind could get through,’ he wrote in his diary.

Sunrise rituals with Michelle Dvorak on Cassin Ridge, Denali, Alaska © Fay Manners

In animal welfare, rivals shouldn’t really exist

Mallory was given the opportunity to be first to climb the mountain, and he did so wearing a tweed suit and without the assistance of oxygen, ultimately failing to reach the summit. Days later Finch was finally allowed to climb using his down jacket and oxygen system, reaching 8,360 metres — the highest any person had climbed — before his exhausted partner forced his retreat.

Two years later, London’s Alpine Club returned to Everest in 1924 in an expedition that saw Mallory leading the climbers, but George Finch was not invited. Instead Mallory’s partner for the attempt was Andrew Sandy Irvine, a chemistry student. Famously, the two died high on Everest in their tweed, carrying Finch’s oxygen system.

Robert Wainwright, author of The Maverick Mountaineer, a biography of George Finch, ponders what might have been if only it were Finch climbing with Mallory: ‘The two Georges could have, should have, conquered Everest that day. And they both should have survived.’

Finch went on to become one of England’s most senior and celebrated scientists and although he’d given up climbing himself, thirty years later he was an advisor and mentor on Edmund Hillary’s successful Everest ascent in 1953. For that expedition, Fairydown, a New Zealand clothing company improved Finch’s original design, creating something remarkably similar to today’s puffy down jacket.

Nearly a century later, if there were to be an unofficial uniform of the outdoors, the down jacket would surely be it. Head to the hills or out on a dog walk and that distinctive design is sure to make an appearance soon enough. Attend any outdoors or adventure gathering and you’re guaranteed to be among a sea of brightly coloured baffles. You’ve probably got your own, perhaps a selection, and for good reason. Down boasts the most impressive weight to warmth ratio of any natural fibre and insane compressibility and recovery attributes making it an undeniably good choice for insulation, be that in a jacket or sleeping bag.

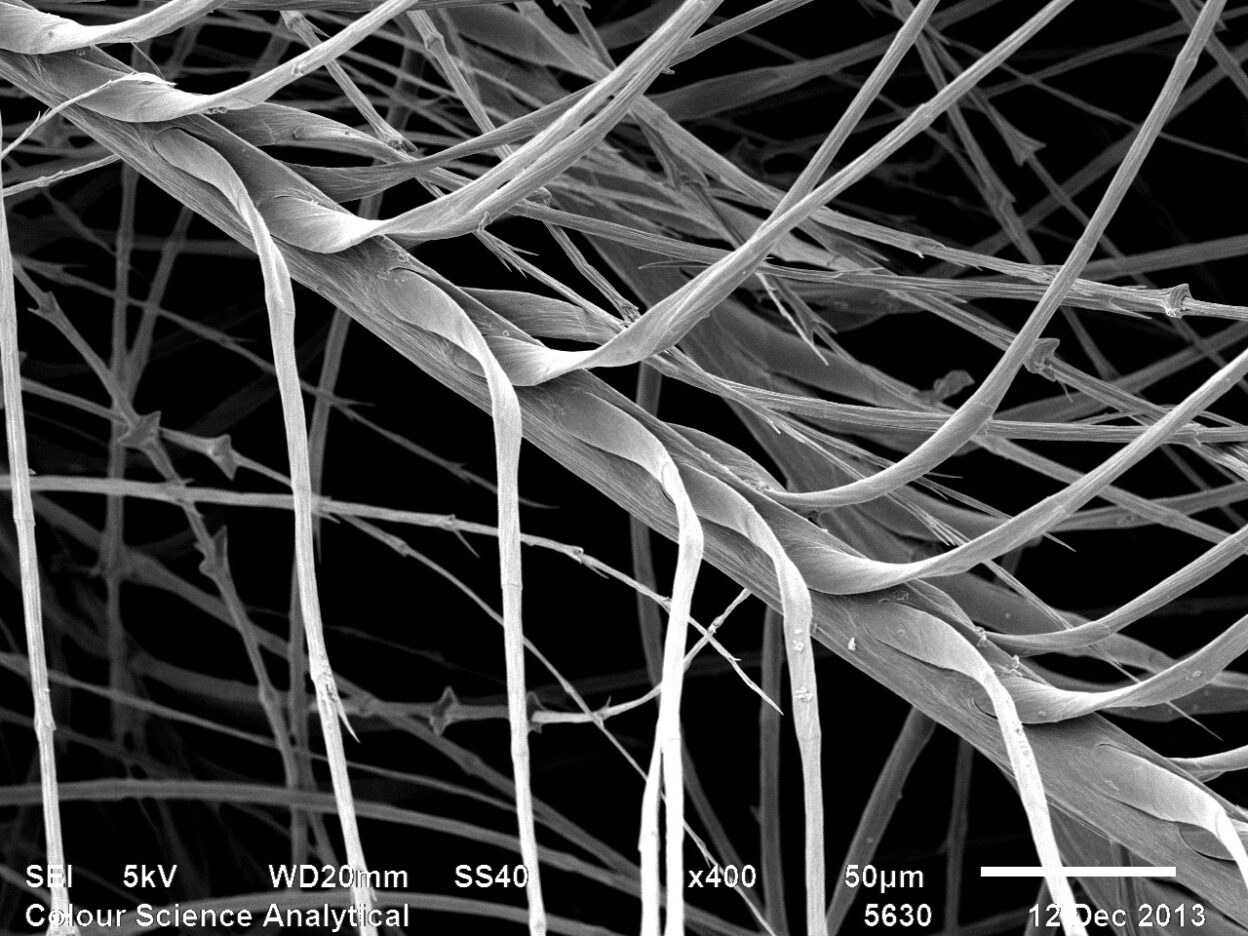

So what is it we’re referencing when we say down specifically? The down of birds is a layer of finer features under their tougher outer feathers. These feathers are simpler than those elsewhere on the birds: they have a shorter shaft (the spine of the feather), fewer barbs (think branches of a tree) and their barbules lack hooks (if barbs are branches, barbules are the leaves). In simple terms, these are smaller, softer, lighter feathers whose sole purpose is to trap air providing warmth and, for some birds, buoyancy in water too.

Raphaela Haug zipped up to tackle the Gabarrou Couloir, Piz Cambrena, Switzerland © Silvan Metz

For decades though, the outdoors has been an industry led by performance and feel above all else. Until relatively very recently, brands overlooked the environmental and ethical impacts of manufacturing as well as the life cycle of those products.

‘For the last 35 years I have done my very best to consume only organic food, especially when it is food from animals,’ explains Tom Strobl, Managing Director of Mountain Equipment in Germany. ‘For the last 33 years I have lived mainly from the sales of down sleeping bags and down jackets. It took me quite a while to think about the animals that deliver the down. Shame on me. I then realised that I can make a much bigger difference if I do my very best to help establish ethical sourcing for our down.’

In 2009, the brand took to redesigning their down supply chains in order to address environmental, ethical and welfare concerns in a project that would later become known as CodeX. The objective was to place animal welfare and sustainability first in all their down insulated products, developing best practice, backed up by comprehensive and transparent auditing.

But, as is the case with most things worth pursuing, it was a bigger challenge than they had first perceived. Largely a bi-product of the meat industry, tracing down is not simply a case of locating the responsible farm, instead it’s a complex network operating at numerous different levels.

‘Indeed a typical down supply chain doesn’t exist, and that’s where the real difficulties began,’ explains Dr Matt Fuller, Product Engineer at Mountain Equipment. ‘One supply chain might have had a mother goose farm, a couple of subsidiary farms, and then a slaughterhouse and down processing plant. Another supply chain might have had two down processors, and multiple slaughterhouses each fed by hundreds, if not thousands, of small farms. Some supply chains relied on a collector-based system with workers riding scooters collecting hundreds of grams of down at a time from rural smallholdings spread out over whole provinces and then taking it to one central processor.’

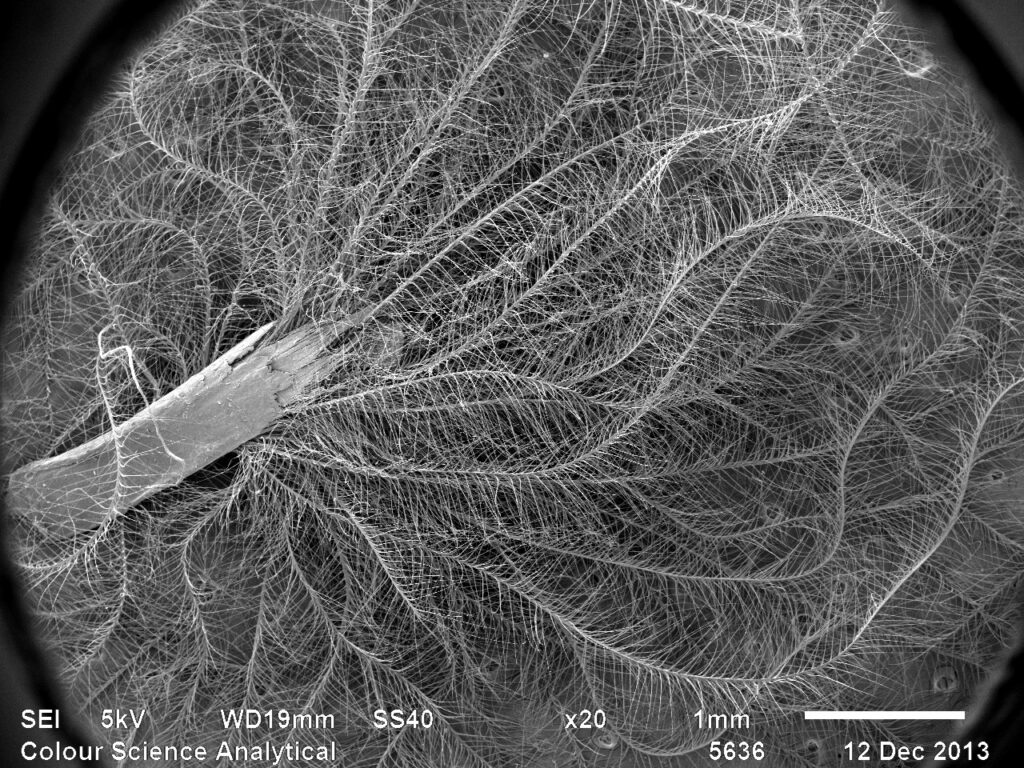

Goose down magnified at X20 shows the sheer quantity of individual barbs from the shaft of feather © Matthew Fuller / University of Leeds

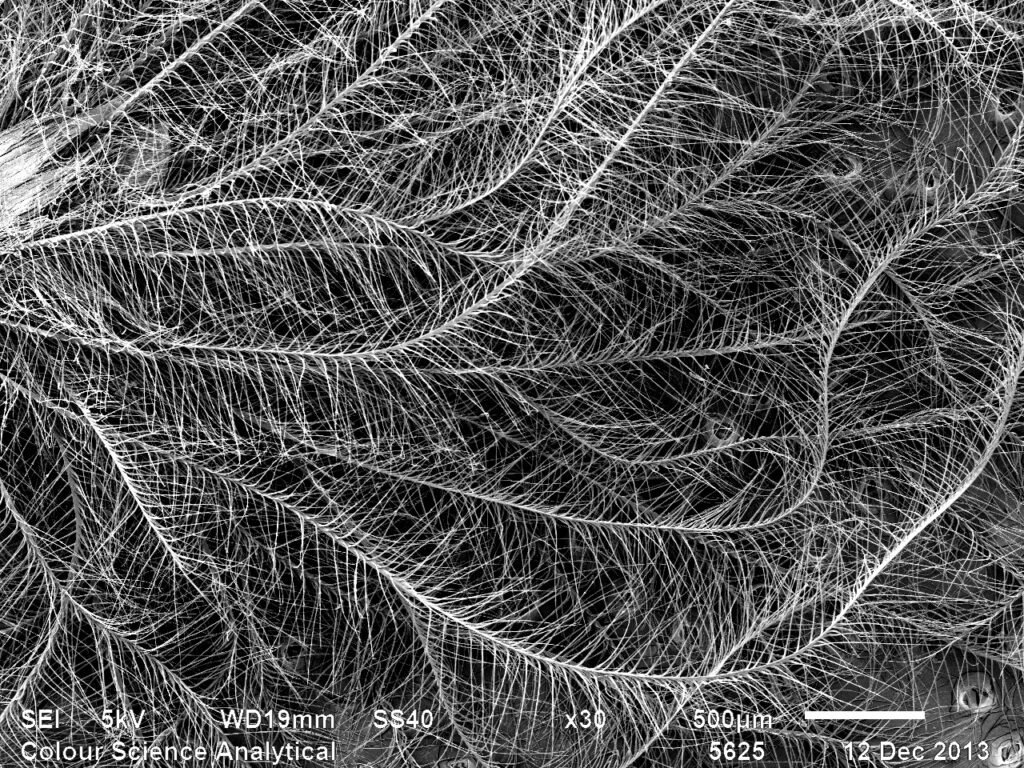

At X30 the individual barbules start to come to light © Matthew Fuller / University of Leeds

With such complex models and so many parties involved, carrying out assessments and audits to provide any form of traceability to implement meaningful change was a mammoth task. And these supply chains weren’t the only problem.

‘The down and feather industry is worth well over a billion US dollars per year and over 270,000 tons of down and feather are traded every year. If we were to come out with difficult demands that suppliers couldn’t achieve, they might simply have decided that we were too much effort to deal with and ignore our small-value orders, instead sticking to larger customers, or those from other industries, who were less demanding,’ explains Fuller. ‘Compared to the down and feather industry, Mountain Equipment was and still is a relatively small brand. Us trying to influence the practices of the down and feather industry would be akin to a non-league football team trying to influence the contracts of football’s highest profile players.’

And, for a team of climbers and fabric specialists with a relatively tiny influence, how would they realistically go about analysing the conditions of animal welfare? Fortunately, as a brand obsessed with quality and performance, they had been working closely for years with the International Down Feature Laboratory (IDFL), the world’s largest down testing facility. They approached them for help in auditing their supply chains and went about building a fundamental framework for animal welfare with the help of the RSPCA’s Freedom Food initiative. The project gathered momentum and before long, horror stories were making headlines from force-feeding and bad living conditions to live-plucking.

‘When the Daily Mail printed the headline in 2012 Gaping flesh wounds, birds crying in pain: The barbaric reality behind the fashion-forward feathers on your winter coat, ethical sourcing of down was suddenly centre-stage and everyone was looking for answers,’ remembers Dr Fuller.

This relatively small brand suddenly found itself at the centre of a huge debate around global animal welfare and international corporations, and massive feather companies were all at the table. To make meaningful change, collaborating over shared information and the knowledge that traceability has no final destination would be vital. More than a decade on and the brand still holds regular meetings with suppliers, auditing and certification bodies as well as competing brands within the outdoors space.

Magnified at X400 it is possible to really see the details within individual barbs and barbules of the feather © Matthew Fuller / University of Leeds

Simply encouraging the recycling of usable but worn products isn’t green, it’s greenwashing

‘We are yet to turn down a meeting with a ‘rival’ outdoor brand,’ he says. ‘In animal welfare, rivals shouldn’t really exist.’

But creating ethical, more sustainable clothing is about more than animal welfare. It’s estimated that globally, 92 million tonnes of textiles waste is created each year and that by 2030, we could be discarding more than 134 million tonnes a year. As a whole, the clothing industry consumes a huge amount of natural resources. It’s an environmental polluter as well as being one of the biggest contributors to carbon emissions and creates a huge amount of waste, owing to problematic end-of-life solutions. Down garments are no exception.

But, unlike many other technical products designed for the outdoors, recycling down is quite straightforward, with as much as 95% of a down jacket or sleeping bag able to be successfully repurposed for another life.

As part of CodeX, Mountain Equipment introduced the use of post-consumer recycled down into a range of insulation, but responsible manufacturing isn’t purely about the sourcing of material. To account for their impact, they wanted to take responsibility for the after-life of their products too, and they went about creating a closed loop recycling system to ensure that unwanted down clothing and sleeping bags aren’t simply thrown away.

In this process, they gather down garments along with unwanted bedding and upholstery to be processed. The down is separated from the other fabrics which can then be chopped and processed to be used in synthetic recycled insulation. The down is then sorted, with damaged feathers and clusters destined to be broken down for use in organic fertiliser. The remaining down is washed and sterilised – with a small percentage of the highest quality reused in recycled down outdoor garments while the remainder makes its way to domestic products like bedding and cushions.

But of course, a recycling loop can only play one small role in creating a more ethical and environmentally friendly solution. Beyond bold claims, sustainability is a delicate and holistic balancing act, taking into account a product’s overall footprint including how it will be used and for how long. Despite progress over the past decade there is still much to do, as we see suppliers and consumers grapple with many of the same existential questions faced by the meat industry, like what ‘humane slaughter’ or ‘good living conditions’ in reality equate to.

‘Simply encouraging the recycling of usable but worn products isn’t green, it’s greenwashing. Recycling only works alongside meaningful steps to reduce consumption. That means taking care of the products we do buy; caring for them appropriately, washing them but only when necessary and repairing them when they become damaged. Above all else it means valuing products for what they have done and the places they have been,’ explains Dr Fuller.

‘This is something that the entire sustainability movement needs to consider. It is becoming increasingly difficult for genuine progress to be recognised among the noise of marketing and the clamour for attention. Greenwashing boldly puts environmental issues front-and-centre, but with these issues hidden behind exaggerated claims or even lies, the real messages are lost and consumers lose out, not knowing what to believe. If environmental and sustainability messages become merely another way for brands to peddle more products, ultimately they have failed.’

This story first appeared in issue 09 of BASE magazine. SUBSCRIBE FOR FREE to get your copy.

Don’t miss a single adventure

Sign up to our free newsletter and get a weekly BASE hit to your inbox

Other posts by this author

Review • Chris Hunt • Jun 27, 2023

Review: Montane Fireball Lite Hooded Jacket

Versatile mid-layer designed for active fast and light adventure

Review • Chris Hunt • Jun 23, 2023

Review: Pas Normal Studios Essential Shield Waterproof Jacket

Premium waterproof cycling jacket

Chris Hunt • Apr 27, 2023

Review: Pas Normal Studios Essential Insulated Jacket

Lightweight windproof insulated jacket from the contemporary Danish cycling brand

You might also like

Review • Mark Bullock • Mar 07, 2024

Review: adidas Free Hiker 2.0 Low Gore-Tex Shoe

A really great, high-performing shoe for a super wide variety of activities.

Review • Alex Smith • Dec 07, 2022

Review: Jöttnar Fenrir jacket

Premium lightweight down jacket from the small British brand

Review • Emily Graham • Sep 14, 2022

Review: Yeti Rambler Kids Bottle

The bullet-proof child friendly water bottle