Home Story Guardians of The Blue

Guardians of The Blue

Feature type Story

Read time 13 min read

Published Dec 01, 2021

Author Will Appleyard

Photographer Will Appleyard

This isolated cluster of exotic-sounding Atlantic islands were wiped off my diving calendar in 2020 for obvious reasons. Come late September 2021 though and nothing could stop me. Despite missing a connecting flight from Lisbon which held me back by 5 hours, I arrived late in Sao Miguel —nicknamed ‘the green island’ — the largest land mass in this archipelago. As I dragged my bags through the rain toward the waiting taxi, I wished, and not for the first time, that my cumbersome luggage had wheels.

My last proper diving trip also involved exploring a remote Atlantic Island, Saint Helena, but my trip to The Azores, many, many miles further north, had an additional purpose aside from sole exploration. I was here for eight days at sea, to dive alongside marine biologists studying manta ray behaviour. Nuria Baylina of the Oceanário de Lisbon (the Lisbon Aquarium) and Pippa Sobral from the Manta Catalogue, were to lead this expedition, tasked with gathering information and images of the species.

I was warmly welcomed aboard the 13 metre catamaran Helia by the beaming smile of Carlos, the skipper, a man I instantly liked and knew would be great fun to spend time with at sea. The crew included dive guide Miguel, the two biologists and from time-to-time underwater camera person, Nuno Sá, working in the Azores to gather whale shark footage for a big-name documentary. I had no idea that we were even in the season for whale sharks here but Nuno practically guaranteed encounters with them for the week ahead.

Right away I felt comfortable aboard this modern sailing-cum-dive boat and got to know my ship mates a little better as we prepared for a local evening check dive by a small island just outside the marina. And, I needed one, I felt a shade rusty after so much time out of the water. We spent the first night aboard moored in the marina, waiting for a weather window to make the 7-hour crossing to the island of Santa Maria, which, even with better weather was pretty lumpy. The weather is subject to sudden change in the Azores, this is simply the nature of remote Atlantic Islands.

Dive site wise, the main focus for this expedition was to perform daily dives at a sea mount called Ambrósio, photographing the rays for the manta ray catalogue. The tip of the sea mount is found 40 metres below the surface and a couple of nautical miles from the island and so pretty much out in the blue. This is where the rays gather at this time of year.

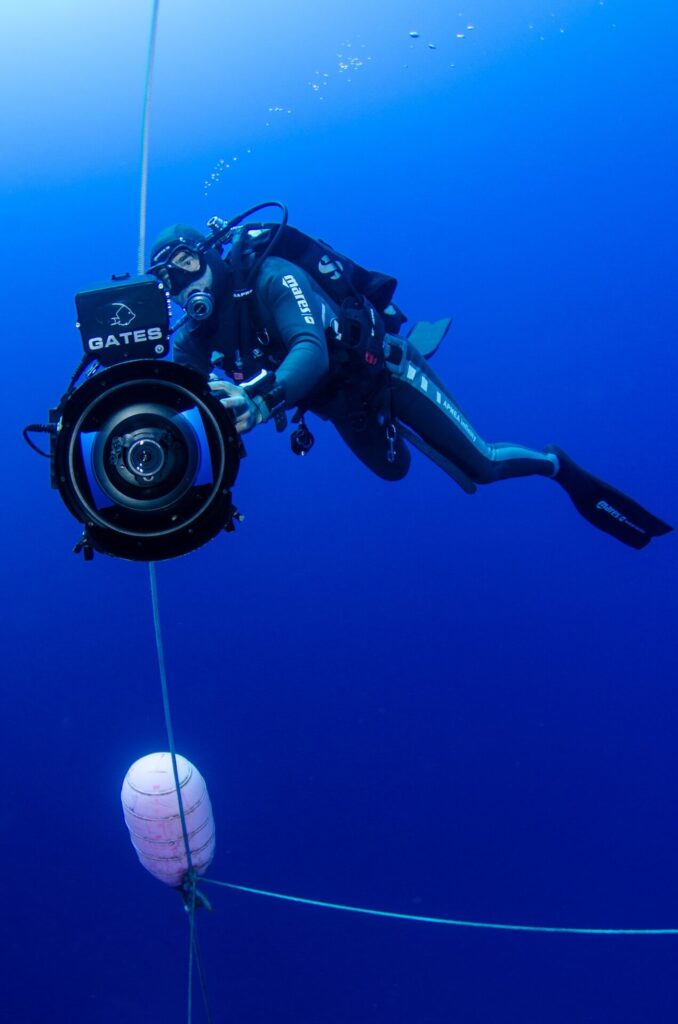

Sightings are so reliable that a pair of fixed buoyed lines, connected horizontally at 20 metres depth have been put in place for underwater observations to be made. At this site, dive boats are required to book an hour’s dive slot, one boat at a time, much like the same successful system used in the Misool marine park in Indonesia. Not only does this system reduce pressure on the animals living there, but also enhances the experience for the diver – fewer divers, fewer bubbles, better visibility.

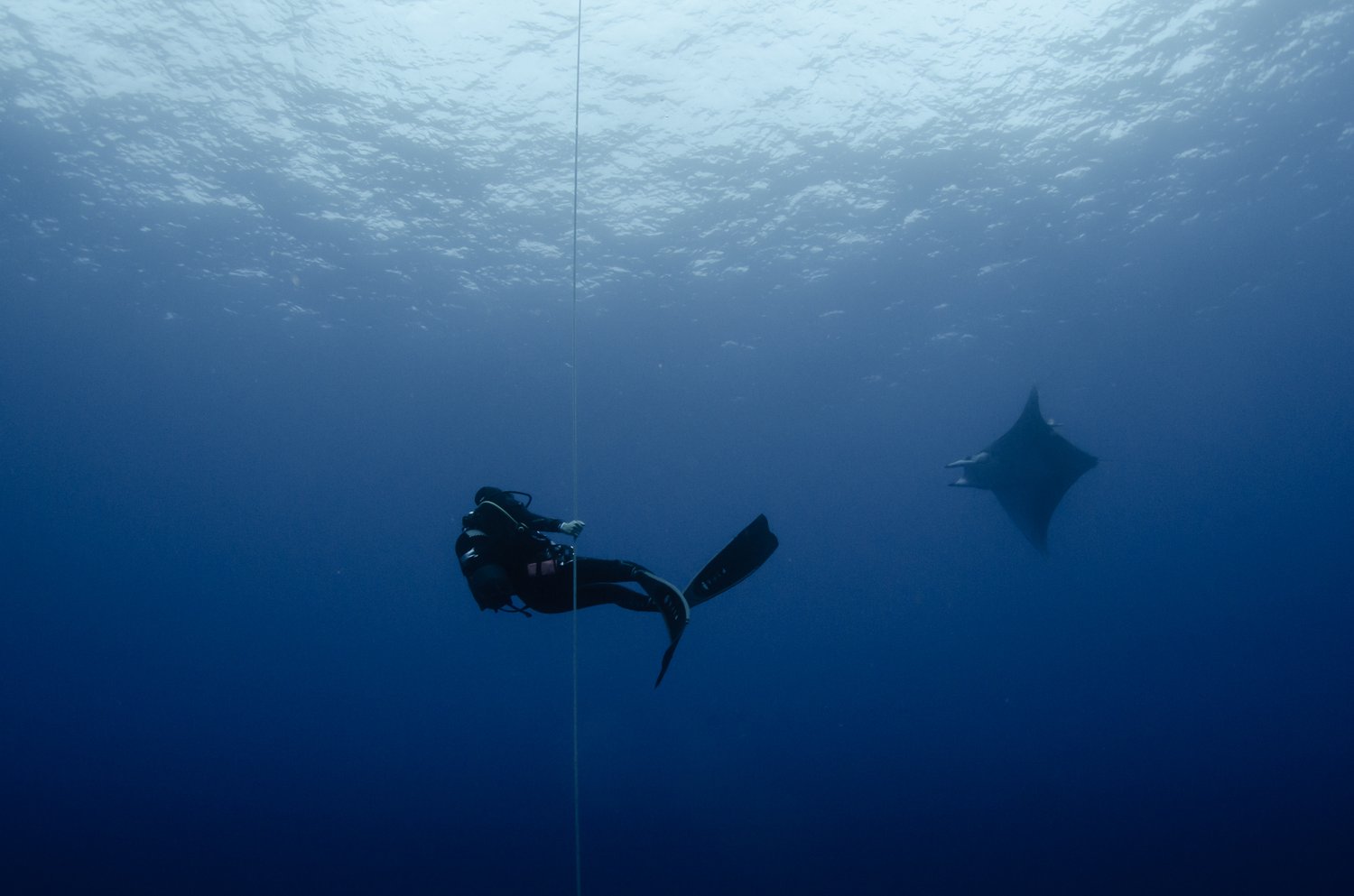

Over several dives at this site, we found that the rays, the Mobula variety of the manta species, would sometimes already be at the surface when the boat arrived, perhaps attracted by the sound of the approaching engine. If not at the surface, they would always appear from the depths as our small team descended the lines, staying with us for the entire hour submerged. For a diver interested in big animals, Ambrósio is a difficult place to leave

For a diver interested in big animals, Ambrósio is a difficult place to leave

This expedition was not only about the mantas. Just one dive per day would be dedicated to the species with the second dive given to explore other sites. A stand out favourite for me would be the Calçada de Gigante or, the Giants Causeway, the exact same kind of hexagonal geological features found in Northern Ireland, but in this location, underwater.

This is essentially the same formation process of molten lava being forced through fissures in the earth to form a plateau of hexagonal pillars and these volcanic features can be found all over Santa Maria Island, not just in the ocean. This scenic dive is vast, the pillars and plateau seemingly endless and a wide-angle wonderland for me as a photographer. A few fish live here too, I passed several groups of grey trigger fish, the same type that cross the Atlantic each year to visit some of my favourite UK based dive sites. Colourful wrasse picked about the rock, while in the blue, barracuda in their hundreds hovered above with menacing mouths and eyes.

But as the week progressed and our days at sea racked up, the idea of diving with whale sharks consumed my mind. Without a single sighting, I began to wonder whether they might not appear for us. However, our time would come, in the form of an explosion of back-to-back wild encounters on our final day aboard. Nuno Sá, the videographer I mentioned earlier had been out chasing whale shark footage on another boat. Around lunch time he radioed Carlos our skipper to say he’d been busy and we should head out on his bearing if we wanted a piece of the action.

Frantic seabird activity over the water is a give-away sign that a bait ball of small fish is near the surface and in turn an indication that something is brewing below. The bait ball chased high in the water by hunting tuna from the deep. Whale sharks and other big animals take advantage of this situation. Carlos found us some activity to the starboard side and we motored towards it, already in our wetsuits, this time with snorkel and no SCUBA.

Once in the water, face submerged I saw the flash of 2 or 3 huge blue fine tuna deep below. Too far away to get a decent picture. All that is left in the water once the tuna leave are fish scales, and the birds had fled as well. We were just minutes too late.

But the end if never so simple in a chase such as this. Patience is key. We climbed back aboard and continued the search. Attempt two found us in the right place. The bait ball was there, Nuno already at the scene filming, but there were no giants feeding – yet. The sea was almost flat, the sun out and Carlos had a great vantage point from the high helm of the catamaran. A further hour spent roaming the ocean, everyone on lookout and we were finally rewarded – birds everywhere at the water’s surface. Carlos yelled for us to jump from the boat and puts us in the water just a few meters from an enormous bait ball. Miguel chooses to dive with SCUBA and I fired off a few shots of him below the moving mass of tiny silver fish. To my right, a large shape appeared from the blue and circled the bait ball – finally we had found a whale shark. The creature, perhaps six metres long headed straight for me, cruising by to my left accompanied by its usual entourage of pilot fish and remora. Nuria pointed out that the animal was carrying a satellite tag and free dived down to inspect it. To retrieve that data will be a marine biologists dream once the tag automatically releases.

Two more slightly smaller whale sharks joined the party, taking turns to dive from view, only to reappear moments later from another direction. I remember partially hearing Carlos whistling from the helm, arm stretched over the side, pointing at something behind me.

The creature, perhaps six metres long headed straight for me

‘Whale!’ he yelled and so I spun with a flick of my fins to find a huge grey mass, growing larger in the blue – a sei whale. The speed of this mammal surprised me. In my mind they were lumbering, slow-moving beings, but no, this whale slid through the water like torpedo and getting a good photo was difficult.

An hour had passed by in the water – looking in every direction, finning, diving down, spitting out mouthfuls of seawater, clearing my mask, clearing snorkel, excitement and awe. Then, finally, in a slow waft of its giant tail, the last whale shark left the scene. I could no longer see or hear the whale either and we had lost the bait ball completely. Just fingers of beautiful light stretched toward the surface, the seabed some unfathomable depth below us and Miguel scanning the blue, five metres below me.

In 20 years of varied diving experiences, these were probably one of the most exciting few hours I have had in the water and to be able to keep a photographic record of that time is a gift. As a team, we carried on beaming about the experience over dinner that evening and I couldn’t wait to break open my waterproof housing to view the images on the computer to relive the experience in photographs.

Don’t miss a single adventure

Sign up to our free newsletter and get a weekly BASE hit to your inbox

Other posts by this author

Story • Will Appleyard • Jan 19, 2023

My Adventure Playground: A Love Letter to Spain

A subjective analysis of what makes Spain the perfect home for the adventure-obsessed

Story • Will Appleyard • May 15, 2020

Deep Way Down

A diver’s journey into the beauty and mystery of the underwater world

You might also like

Video • BASE editorial team • May 09, 2023

Top Five Scariest Things About Scuba Diving

Tips and tricks to overcome your fears, find your sea legs and take the plunge

Story • Ben Horton • Jun 28, 2022

A Deeper Understanding

Lessons in facing the unknown in Mexico's underwater cave systems

Story • Hannah Bailey • Jun 18, 2020

Learning the Lessons from Jeju with Filmmaker Nicole Gormley

Chatting connection to the ocean, filmmaking and time spent with the haenyao of South Korea