For many of us, access to adventure in the outdoors is something we take for granted. It provides a place to unwind, somewhere free of the constraints of daily life, representing an opportunity to escape and reconnect, perhaps hone a craft. But it’s a privilege not readily available to everyone. For Adam Raja, growing up in the urban outskirts of Glasgow, finding his own route to the mountains was far from straightforward.

Now a keen climber, adventure photographer, and climate activist with Protect Our Winters, the BASE Collective member candidly explores his experiences of both sides of Scotland – from inner-city gang culture, knife crime and drug and alcohol abuse, to the steep-sided valleys and towering peaks of Glencoe. Exploring identity, cultural heritage and connection to landscape, this is Adam’s story of finding place, identity and community in the mountains.

Adam at a belay on Dorsal Arete in Stob Coire Nan Lochan, Glencoe, Scotland. From a Berghaus Extrem photoshoot. © Hamish Frost / Berghaus

I was perched beneath Vanishing Gully, my first truly vertical winter climb on the north face of Ben Nevis. Not cold, but nervous; a shiver ran across my shoulders as I took in the dark buttresses above. The approach had put me on edge. It was the end of the winter season, and the fickle Scottish weather meant that multiple freeze/thaw cycles had turned the lower slopes into steep sheets of ice that led to the rocky cavities below. Willis stopped for a breath and turned to Rob and I, ‘You don’t want to fall here.’

He was right, I didn’t. I peered down the steep slopes to the rocks below and questioned what it was I was doing there. I’m always battling self-doubt, but beneath the anxiety I was excited. I had spent the last few years soloing low-grade winter routes, fantasising about having a group of friends to climb with. And here I was, staying at the CIC hut beneath Ben Nevis for a four day climbing trip with 15 other climbers.

I was relieved to reach the base of the route. We faffed with gear, flaked ropes, and laughed amongst ourselves as we prepared for the first climb of the trip. Then the radio beeped.

‘Willis, it’s Matt. Come in.’ Matt’s voice was shaky, and the crackle didn’t conceal the urgency.

‘All okay, Matt?’ Willis replied.

‘Hannah’s fallen. We need a rescue.’

Excitement turned to dread. That sick, sinking feeling pushed its way from my chest to my stomach. A feeling I became acquainted with as a teenager. Willis, the most experienced among the group, set off to assist at the base of the route where the fall had happened. I called Mountain Rescue, passing on the details to the operator the best I could and we waited in the snow hoping for good news.

The North Face of Ben Nevis at sunrise from the summit of Càrn Mòr Dearg. © Adam Raja.

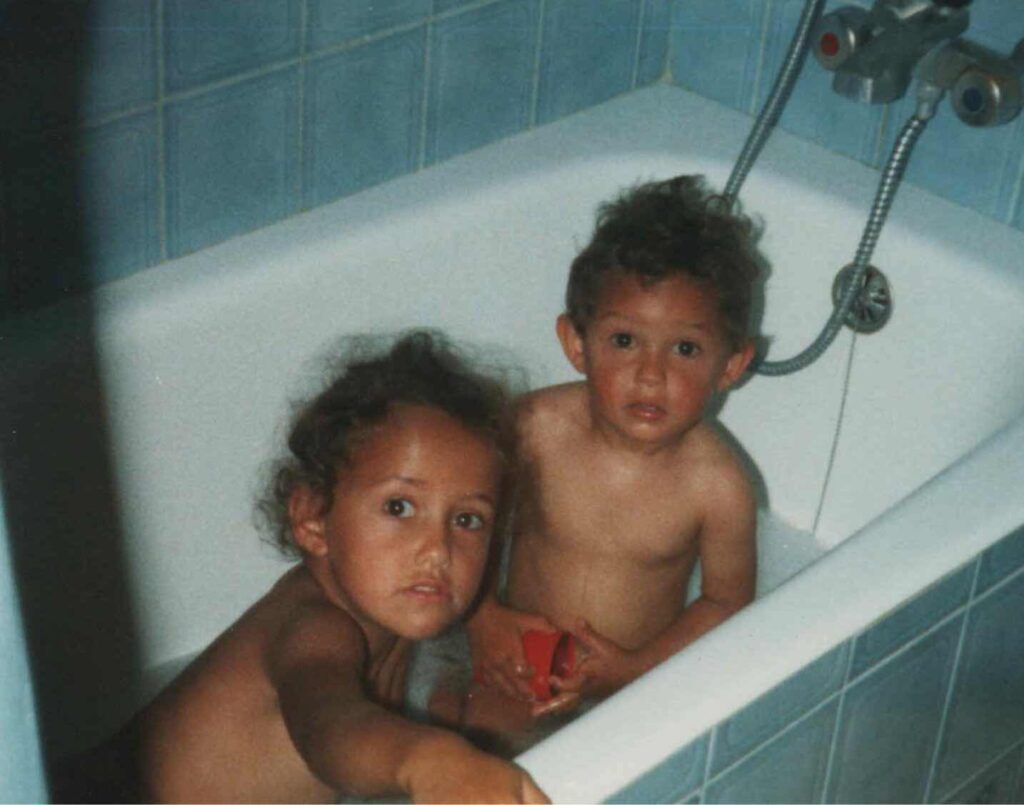

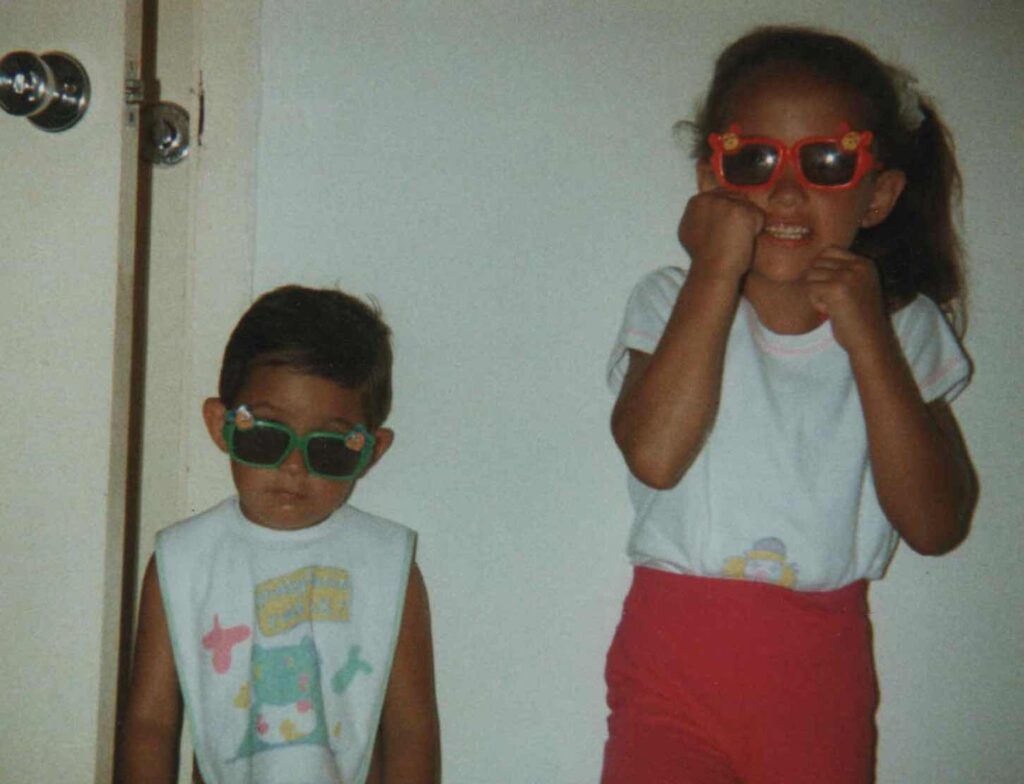

I had never been to Pakistan; our mother and grandparents were both white and Scottish, and we enjoyed Irn Bru and square sausage as much as anyone else

As the cold set in, a thought entered my mind: mountaineers often die. I shook my head and muttered to myself: so did gang members and drug dealers. Unfortunate timing for such intrusive, but nonetheless real, thoughts. I dwelled on it over the next few days on the mountain. It was the first moment I recall being confronted with the reality that I was once again living a high-risk lifestyle; where violent injury and death weren’t uncommon, where your peers could be here today and gone tomorrow. Threats which had plagued my adolescent years that I’ve spent much of my adult life trying to bury.

I grew up in Cumbernauld, a satellite town of Glasgow that inherited the city’s overflowing population, as well as the social issues that gave it its rough reputation. I reached adolescence in the ’00s, a time when alcoholism, drug misuse, gang culture, and violent crime were all too prevalent. In 2005, the number of violent deaths was so high that the World Health Organisation reported that Scots were three times more likely to be murdered than people living in England or Wales. Glasgow was dubbed the Murder Capital of Europe and in 2020, drug-related deaths increased for the seventh consecutive year, with a rate 3.7 times greater than that of the UK as a whole and higher than any other European country.

When I dwell on my childhood, what I remember the most is feeling like an outsider, and inferior to my peers. My father is from Pakistan, and a paki, I soon found out, was the last thing you wanted to be, but despite our entirely typical Scottish upbringing, the label soon found my sister and I. English was our first and only language; I had never been to Pakistan; our mother and grandparents were both white and Scottish, and we enjoyed Irn Bru and square sausage as much as anyone else. Still, our brown skin and second name were enough to single us out and push us down the pecking order.

The first time I recall being called a paki was when I was in primary school, perhaps 8 or 9 years-old. A friend and I were playing together after school when, in an underpass, we ran into a classmate of my sister’s. Martin was four years my senior, and he was drunk. As we approached, without warning, Martin grabbed me by my school jumper: ‘You and your sister are fucking pakis!’ he said and punched me in the face. I cried and ran back towards my gran’s house. I wiped my face, sat in her living room, watched cartoons, and ate cereal.

I never told anyone about that encounter or the many other incidents that followed. I didn’t know it at the time, but for years I struggled massively with my identity because of these experiences. I wanted to be anyone, or anything, other than that which I had been labelled as and punished for. I felt Scottish, but it became apparent that I wasn’t – or at least not Scottish enough. I became increasingly sensitive and reclusive, opting to sit in front of the television and play computer games rather than play outside and expose myself to those kinds of situations. I looked to food for comfort, and my weight increased as my happiness decreased. I also grew to hate my absent father for what I had inherited from him, and when he chose to indulge in alcohol over family, distancing myself from him became an easy choice. I craved acceptance, belonging, and respect, but I wasn’t going to get those things with brown skin and a surname like Raja.

As I entered my early teens, these experiences, and perhaps the lack of a positive father figure, left me vulnerable to the negative influences that plagued Glasgwegian culture. Postcode gangs, known locally as young teams, were common, and I inadvertently found myself amongst them hoping to find the acceptance and mentorship I couldn’t find elsewhere. Alcohol and drug abuse at a young age wasn’t just accepted, they were the status quo. I drank heavily and often. It was one of the few things that would lift the unease I felt in my brown skin. It was also something that later, finally gave me the courage to stand up for myself when I was targeted for my ethnicity.

As we grew older, and despite my gentle nature and a strong aversion to violence, exposure to it became a common occurrence. I saw my peers become both victims and perpetrators. One evening after school, I went to my friend Rambo’s house with another friend, Brian. I liked Brian. He had a don’t fuck with me vibe about him, but he’d always been friendly to me. We sat in Rambo’s small bedroom listening to 50 Cent and playing PlayStation before deciding to head to the local park to see if any of our other friends were around. Brian was originally from another scheme in Glasgow, and unbeknown to me, the local young team had taken a dislike to him for it.

On the slopes of Beinn a Chrulaiste in winter. The impressive Buachaille as a backdrop. © Adam Raja.

On our walk to the park we passed a small shop that sat within a tunnel beneath a block of flats. Stood in the tunnel but concealed by the harsh shadows, was a group of boys that I knew from the area. One of whom was Rambo’s cousin. Without talking, they emerged and produced weapons – a hammer, and glass bottles. We scattered in separate directions, and they gave chase. The boy with the hammer pursued Brian. Another two ran after me and I was eventually cornered in an underpass. Scared and winded, I put my hands up. ‘I don’t have a problem with any of you,’ I said in defence. I was punched and a bottle was smashed over my head. Rambo watched from the entrance to the tunnel. The attack damaged my right eye and left a deep gash across my eyebrow. I was 14, but I still carry the scar on my face today.

As I stumbled home to my mum, Brian ran home to get his baseball bat. He found two of our attackers later that evening and retaliated. He nearly killed one of them, leaving him in intensive care with serious head injuries and a permanent loss of smell. The other escaped with a broken arm – he and his father sat across from my mum and me as I awaited treatment for the wound on my face in A&E. We never acknowledged one another, and I suspect neither of our parents knew how we really got those injuries.

I never saw Brian after that night – he returned to the city to hide from the police and was eventually arrested and imprisoned for the attack. I never found acceptance either. My affiliation with the local young teams, and the courage I gained from alcohol may have meant that the average kid in school treated me a little better because they heard about the company I kept. However, I was also exposed to increasing violence and crime, and found myself living a life of angst. I couldn’t walk home from school, or go to the shops with my mum without worrying about who we might bump into. I watched my peers, like Brian, go to prison, and I saw others abuse alcohol and drugs to the point that some went to sleep and never woke up. As we grew older, options and opportunities dwindled and we had no one and nowhere to run to. We certainly weren’t dreaming of mountains.

I can’t justify Brian’s actions but I do understand them. We were young men, without positive male role models at home, trying to stay afloat in a place where a propensity for violence was rewarded and weakness punished. If Brian hadn’t put his attackers in the hospital that night, I suspect that he would have found himself in the beds that they occupied sooner or later.

I’ve seen Scotland from above and below – from its rock bottom to its highest peaks

Self portrait at blue hour on An Teallach, Dundonnell. © Adam Raja

I never became comfortable with violence, but the constant conflict taught me how to function in places and situations that scared me. Leaning into my fears removed the confines they created – if I hadn’t, I’d most likely still have been sitting on my gran’s living room floor watching cartoons, temporarily sheltered, but stunted by fear of the next encounter.

You can draw ironic parallels between the extreme privilege of those who explore the mountains for leisure and those living in deprivation in the communities below them. Danger presents itself often, and the risks and repercussions are almost equal in severity. Make the wrong decision on Ben Nevis, or simply be in the wrong place at the wrong time, and you too could find yourself in a hospital or worse. A rockfall or avalanche is just as deadly as a hammer or baseball bat in the wrong hands.

I thought about these parallels on the Ben that day – and I still think about them now. I wondered if our lives were at risk. Was this any better than the life I had escaped? Had my childhood trauma steered me toward the mountains in search of danger? And was I not happy unless I put myself at risk? But despite the parallels, the similarities stop there. One is a lifestyle choice that requires significant privilege, the other is a set of circumstances that come from deprivation and struggle.

Adam Raja having a hot drink in the summit shelter of Càrn a’ Mhàim on a cold and windy morning in the Cairngorms. © Rachel Jack

People from my background didn’t climb mountains. Our role models were crooks, our fathers were absent

I don’t seek danger in the mountains, I seek adventure. The Scottish Highlands are a playground that’s a startling juxtaposition to the Scotland I had come to know. Scrambling and climbing my way across the mountains isn’t me reliving my precarious youth; I’m exercising my newly found and untethered freedom by intimately exploring a world that was once veiled beneath despair but now represents hope. There are risks yes, but for the most part they can be managed, and are a small price to pay for the joy and optimism I feel when I find myself in the most incredible situations.

I’ve seen Scotland from above and below – from its rock bottom to its highest peaks. Something most of my peers never got to do. But it wasn’t an easy transition, there are a lot of barriers to overcome and I was in my 20s before I even realised there were mountains in Scotland – certainly, before I entertained the idea of climbing them. People from my background didn’t climb mountains. Our role models were crooks, our fathers were absent, and our mothers were tired and constrained by the pressures of being a single parent.

It was social media that introduced me to the outdoors. I was amazed when I first saw photographs of Glencoe, and its rocky ridgelines and conic peaks. I couldn’t believe that they were just a stone’s throw away from Glasgow, and yet I had never seen them. Glencoe, and Scotland’s other outdoor havens, were only put on my radar once I had acquired a certain level of privilege. University played a huge role. It’s somewhat of a cliché, but the opportunities offered at university, particularly an Erasmus exchange to France, broadened my horizons and opened me up to new experiences. This meant that when I became aware of the mountains, I approached them with curiosity and intrigue rather than apathy.

Even with this awareness, it wasn’t until I had a job, disposable income, and a car that I could actually make my way to the hills, regardless of their proximity to Glasgow. Once I had these things, one of the first trips I made in my new car was to Glencoe, which in hindsight, was maybe one of the most important decisions of my life. As I drove through the Glen my jaw sat in my lap for much of the journey. I had never seen a place like this, and it was almost incomprehensible that I had left Glasgow less than two hours earlier. As I sat in a layby, eating my lunch, I stared up at the daunting Buachaille Etive Mòr. I had to climb it.

Oz Miller and Willis Morris on Curved Ridge in Glencoe on a precariously mild morning in December 2021.© Adam Raja

Glencoe’s mountains captured my imagination that day, and I’ve been captivated ever since.

My career, my hobbies, my interests, and my free time all revolve around the outdoors. It may sound a little melodramatic, but the outdoors and the experiences I’ve had in the outdoors have been truly transformative. I can’t say the outdoors saved me, but what I can say is that my time and experiences among the mountains have given me a significantly better quality of life than I had in the many years prior. One that I had lost hope of at one point. I have an identity, something that evaded me and I’ve struggled with most of my life. I also have a community and feel a sense of belonging, which has been missing since I removed myself from the gangs and other negative influences that surrounded me in Cumbernauld. Most importantly, I have found purpose in life, and it’s what drives me to do the work that I do today.

The outdoors has been good to me, and I think it would be a tragedy if we robbed others of that opportunity. So welcoming others, especially those who have historically not been or felt like part of the outdoor narrative, has become very important to me. It may turn out that it’s not for them or just simply doesn’t impact their life in the same way. But that’s fine, at least they have had the opportunity, and isn’t that what matters most? Because it was the lack of opportunity, or the barriers that concealed them, that held me and my peers in place for so long.

The other facet is climate action. Without my experiences in the outdoors, I would never have forged a connection with nature or been able to join the dots between environment and climate change. So a failure to remove those barriers and welcome more people into the fold in the first place is a failure to protect these places from climate change, thus further robbing future generations of these experiences. I think that’s why all of us, who find ourselves in the position to play in the mountains, should do our bit to protect the places we play and open the door for others who aren’t so fortunate.

A failure to remove those barriers and welcome more people into the fold in the first place is a failure to protect these places from climate change

The amazing Buachaille Etive Mor from Beinn a Chrulaiste at blue hour. © Adam Raja.

Hannah sustained some severe injuries that day on The Ben, but I’m pleased to write that she’s made a heroic recovery and is back training and climbing. I’d like to imagine that I too would demonstrate such grit and spirit. Mountaineers and climbers do die on occasion, but it’s a risk that comes from opportunity, freedom of choice, and privilege. The risks we faced growing up were neither – they were the result of a lack of. As soon as I had an opportunity to remove myself from the situation I found myself in, I took it.

I don’t care how fast I climb a mountain, what grade the route is, or how many footsteps proceed mine. The fact that I’ve stood on a mountain at all is what’s meaningful to me – especially when I know where the steps of my peers led them. I’m grateful every time I get to stand on or amongst the mountains. I can’t say I felt the same way when it was only concrete that towered above me and the most prevalent risk was falling victim to violent crime. I’ll take the risks associated with mountaineering over that any day of the week.

This story first appeared in issue 09 of BASE magazine, you can get your own physical copy or subscribe for FREE here.

Don’t miss a single adventure

Sign up to our free newsletter and get a weekly BASE hit to your inbox

Other posts by this author

Spotlight • Adam Raja • Jul 07, 2023

A Mountain Of Heritage: Klättermusen x Britta Marakatt-Labba Collaboration

The Sámi textile artist discusses her collaboration with the Swedish brand and the importance of weaving heritage throughout the range