For classic bicycle enthusiasts, no number is more iconic than 531. Harking back to a golden era of bike racing, those three digits represent a time before the superlight carbon fibre shapes which dominate pro pelotons today. Back then, boundaries weren’t being pushed; they were being set for the very first time and the 531 stamp on the inside of the seat tube defined the era. Whilst technological advances over decades have led frame builders to lighter materials, as the line between off-road and road bikes begins to blur there’s a resurgence in the use of steel for cycle tubing at a time when bike-based adventure travel is booming.

Italian tubing giant Dedaccaia is one of the world’s leading manufacturers of steel tubing used in modern bikes. © Mason Cycles

The Story of Butted Steel Tubing

In 1897, Alfred M. Reynolds, the son of a nail manufacturer in Birmingham looked at the same puzzle which had been haunting frame builders for many years and, with a fresh approach, he revolutionised the engineering of bicycle frames. By thickening the walls at the ends of the tubes, he patented the tube butting process. Keeping the centre of the tubing thin removed weight from the tubes, and by thickening the ends where the tubes were joined, it did so without compromising strength. It was this technique which made the Reynolds name synonymous with steel tubing in the bike industry, where today, alongside the Italian tubing giants Columbus and Dedacciai, the British company remains an icon over a century later.

His new approach quickly attracted attention beyond the realms of the cycle industry. In World War One, Reynolds was called upon by the government to produce tubing for military bicycles and motorcycles, and even in the frames of military aircraft. After the war, the focus soon shifted back to the application of butted tubing for bike manufacturing and in 1935, Reynolds launched the 531 brand.

‘When it was released, it was the first high performance material developed specifically for the cycle industry and was significantly stronger than any material that had come before it,’ explains Tom Cleverley, Project and Development Engineer at Reynolds today.

Of course, steel in itself is not a naturally occurring element but rather an alloy, a combination of metals specifically selected and melted together for purpose. 531 in this case is said to have been coined from the ratio of alloying elements within the steel – 5 parts manganese to 3 parts carbon and 1 part molybdenum.

The high strength of the chosen metals alongside this patented butting process meant exceptionally light frames were being built. When World War Two broke out, once again Reynolds was enlisted into Britain’s effort as 531 constructed the wing spars for Spitfires, subframes for Lancaster bombers and Rolls Royce Merlin engine mountings.

In 1947, after the end of the Second World War, the Reynolds frames advertised weighed more than half a kilogram less than they had at the turn of the century. 531 was so good, it remained the state of the art for four decades and was used to create the front frames of the Jaguar E-type of the 1960s.

‘This technology could be utilised on all bike frames but was particularly well suited to racing frames’, Tom tells me. ‘21 Tour De France wins later – starting in 1958 with Luxembourg’s Charly Gaul and later including the likes Eddy Merckx and Jacques Anquetil – 531 cemented its place in cycling history. The 531 decal on the seat tube became a badge of honour for builders and riders alike. I suppose the true test of an icon is how it manages to transcend the world of cycling. People may not know a great deal about cycling or even Reynolds, but if you ask them there’s a fair chance they’ll have heard of 531. This is something I still see today.’

Steel Frame Building in the Modern Era

Today, 84 years after its launch, and besides nostalgia and the second-hand market, 531 tubing is largely obsolete. Bike companies looking to evolve into lighter, faster machines, opt instead to work with aluminium, carbon and titanium. But with the rise of gravel and adventure cycling, along with the rebranding of cycle touring as bikepacking, steel is an increasingly popular option for progressive frame builders and the evolution of the steel alloys used today, means that steel bikes are far from a relic from a bygone era.

‘Steel is an excellent bicycle frame material. It’s easy to form, very tough and durable’, explains Dom Mason of Mason Cycles. ‘It also responds very well to welding and brazing. Steel bikes are often described as having ‘spring’ and ‘life’ to them which is a combination of the materials, using the correct tube shapes and sections and also of good design in geometry’.

Based in Brighton, Dom’s bikes have become known as fast, mile-crunching machines and are a regular feature of ultra-endurance events around the globe. ‘Modern tubing has a large diameter which allows it to retain its strength when very thin wall sections are used, this makes it possible to build lightweight frames which are long lasting with a lively feel’, he tells me.

So what’s the best type of steel to use in today’s adventure category of bikes?

‘Generally, I use the best blend of tubes for the particular model that I’m designing, to give it the correct balance of riding properties, toughness, durability and physical dimensions,’ Dom explains.

For each frame Mason Cycles designs, the variations in steel tubing combine to best suit the intended functionality of the bike in question. The requirements are so specific in fact that each tube set they use is custom designed and made specially using a combination of tube profiles, shapes and bends.

‘Our latest frame, the InSearchOf, uses steel construction for a perfect combination of ride quality, comfort, toughness, durability, dependability and weight,’ says Dom. ‘The major objective for this bike is to provide a machine that can move very fast across hugely variable terrain and will transport a rider and everything he or she requires, for self supported, ultra-distance riding. The aim is that it should never leave the rider stranded because of the terrain or because of physical damage to the frame. Many riders don’t trust carbon because it can be damaged by dropping a loaded bike on a rock or a broken rear mech smashing itself through the chainstay. If you’re deep in the wilderness this can be end your race or be life threatening. Steel is much more resistant to damage and can be more easily repaired using conventional means, so help is never too far away. The bike needed to be very comfortable for many many hours in the saddle and also confidence inspiring and forgiving on steep and loose terrain, when fully loaded and with a fatigued rider. It also had to retain a lively and engaging ride. Taking all these factors into consideration, steel construction simply provides the most advantages, using a blend of Italian Dedacciai and Reynolds 853 tubing.

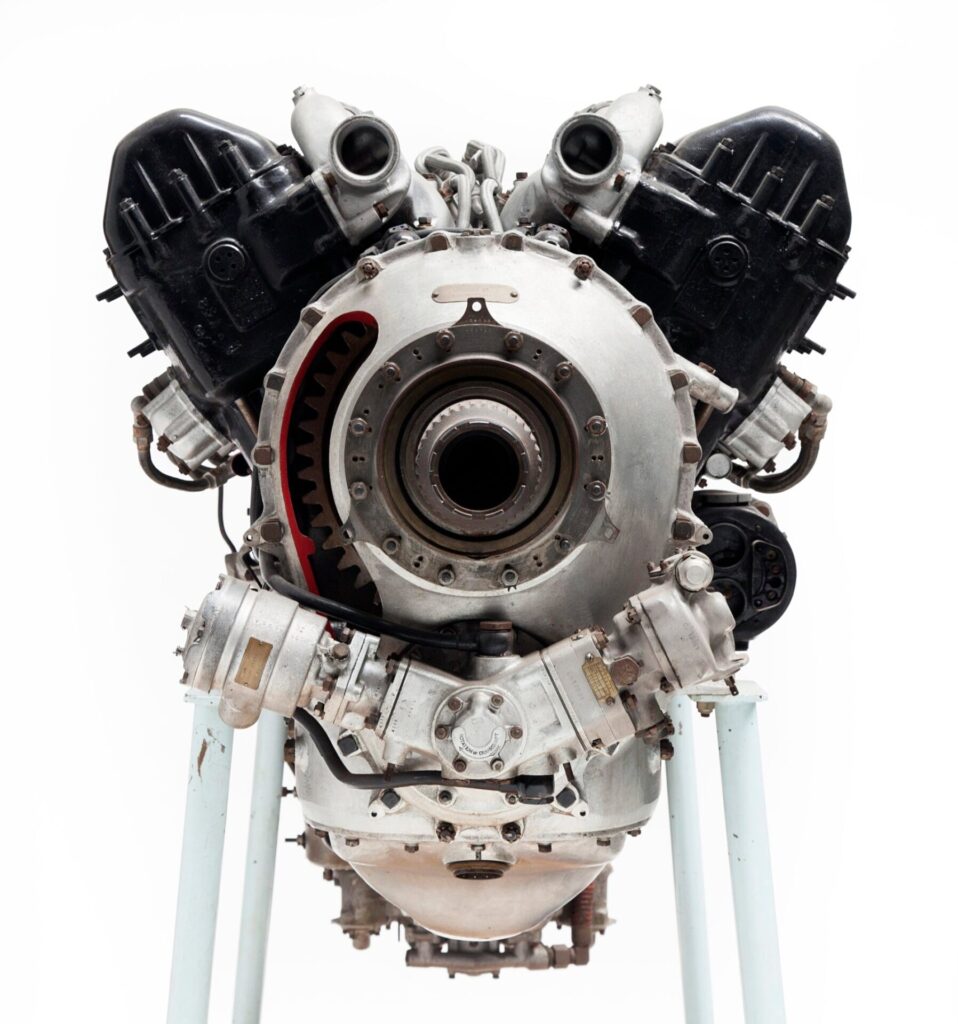

The Rolls-Royce Merlin engine, an early version of which was used in the legendary WW2 Spitfire fighter plane used Reynolds 531 butted steel engine mountings.

Reynolds 531 was used for the wing spars of the Spitfire fighter, the subframes for Lancaster bombers, and Rolls Royce Merlin engine mountings

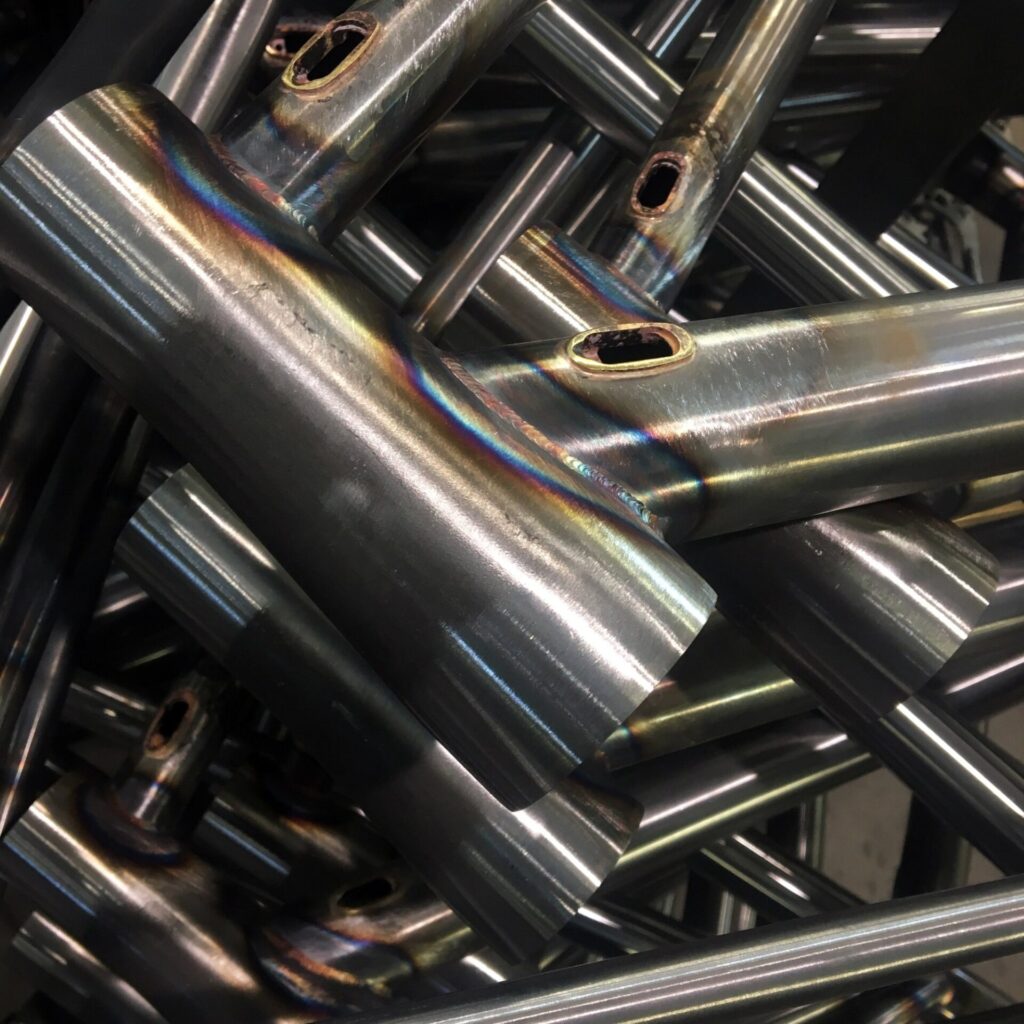

Steel bike frames made with Columbus tubing ready for the next stage of their manufacturing process. © Mason Cycles

Detail of the headset unit of a steel bike frame: stronger and more easily repaired than carbon fibre. © Mason Cycles

As in all sorts of industries, for bicycle consumers, a connection with the process of how their new bike came to be, the work that entailed and the crafts people behind it is increasingly attractive. The opportunity to develop a personal relationship with a local or perhaps renowned frame builder and customising the frame down to the smallest details provides a unique experience to selecting your new bike; an experience which simply can’t be matched by a visit to the likes of your local bicycle megastore.

‘For custom frames, it [steel] is perfect. It is relatively easy to work with and builders don’t need to invest in expensive moulds like carbon fibre or post weld heat treatments as they would with aluminium’, says Reynolds engineer Tom Cleverley. ‘I also think people are becoming more environmentally conscious of the products they buy. They want something that’s going to last and isn’t inevitably going to end up on the scrap heap at the end of its life. The fact that materials such as 921 come from solely recycled sources and can be recycled themselves only can only add to that appeal.’

The Age of Super Steel

Today, Reynolds’ flagship composite 953 boasts a tensile strength of over 1650 MPa, which means stronger, lighter and more versatile tubing creating the new generation of adventure bikes in what Reynolds have tagged ‘the age of super steel’.

‘The myth that steel means heavy by default is gone. 853 and 953 effectively dispelled that’, says Tom Cleverley. ‘Now, you have a tube set capable of holding its own with all but the very lightest carbon fibre race bikes’.

For traditional cycle tourists, steel frames have for decades provided the perfect platform to be loaded for long distance tours. Now, with lightweight camping kit being smaller; the introduction of bikepacking bags attaching directly to handlebars, seat posts and top tubes and the popularity of self-supported ultra-endurance riding going through the roof; we’ve entered the era of true ‘go anywhere’ bikes.

‘You only have to look at the frames coming from the likes of Fairlight, Stanforth and Mason to see where steel really excels’, Tom points out. ‘It’s strong, tough, and with the appropriate tube diameters and profiles a very responsive yet compliant ride can be achieved – the famous ride of steel. We’re seeing steel being ridden by Transcontinental race winners and round the world tourers alike. Those kinds of riders both want a bike that is going to carry them fast, far and in relative comfort whilst withstanding a hefty amount of abuse. Reliability and comfort tend to trump overall frame weight when you are miles from the nearest town let alone the nearest bike shop.’

So, what does the alloy composite of today’s leading adventure steel look like? I ask Tom Cleverley for his view.

‘The true composition of 953 is sworn to secrecy. Even I am not allowed to know it,’ he says with a grin. And while a part of me really wishes that was the case, he soon concedes to admitting his joke. Pride in his product perhaps.

‘It’s a patented alloy made for us by Carpenter Special Metals in the US. A maraging stainless steel that gets its strength from the formation of intermetallic precipitates – Iron nickel lathe crystals – after heat treatment’ he explains. ‘It is hard to work and unforgiving on tools, but it does allow for the creation of some exceptionally light weight steel frames.’

The numerical names of today’s super steel however, while a nod to the likes of 531 in the past, have little reference to the ratio makeup of the alloy. ‘The modern names are decidedly less romantic, more an exercise in branding’, he says. ‘There is a link in that the higher the number, the higher the strength generally speaking. The 900 series is our range of stainless steels, but with a yield of 1450 MPa and a tensile strength of 1650 MPa. Reynolds 953 should really be called 1650.’

The overall trend here is that despite all the advances in carbon fibre, steel remains an outstanding material for adventure bike frames – it’s very strong, very light, and doesn’t suffer from the same problems of catastrophic failure that carbon fibre does. It’s easy and cheap to weld and repair a steel frame; repairing a carbon frame is much more complicated.

Over a century after Alfred M. Reynolds’ groundbreaking invention of butted steel tubing, steel bike frames are clearly here to stay.

This article first appeared in issue #02 of BASE magazine. Click here to read the full issue online. For more deep dives into adventure technologies like this one, click here.

Don’t miss a single adventure

Sign up to our free newsletter and get a weekly BASE hit to your inbox

Other posts by this author

Review • Chris Hunt • Jun 27, 2023

Review: Montane Fireball Lite Hooded Jacket

Versatile mid-layer designed for active fast and light adventure

Review • Chris Hunt • Jun 23, 2023

Review: Pas Normal Studios Essential Shield Waterproof Jacket

Premium waterproof cycling jacket

Chris Hunt • Apr 27, 2023

Review: Pas Normal Studios Essential Insulated Jacket

Lightweight windproof insulated jacket from the contemporary Danish cycling brand

You might also like

Review • Sam Firth • Mar 22, 2024

Review: Rapha Men’s Explore Lightweight Gilet

A stylish, lightweight and packable cycling layer.

Review • Matthew Pink • Jun 29, 2023

Review: Albion Zoa Rain Trousers

Waterproof trousers for on and off the bike

Review • Chris Hunt • Jun 23, 2023

Review: Pas Normal Studios Essential Shield Waterproof Jacket

Premium waterproof cycling jacket